C. G. Jung

C. G. Jung

Jung's Psychology of Consciousness

I. Psychological Types (see Snider, pp. 12-13)

A. Introversion: the libido (psychic energy)

is turned inward, away

from the object, into the subject.

B. Extraversion: the libido is turned

outward,

toward the object

II. Functions of Consciousness: these are divided into four.

A. Thinking (this type relates to the world

via thought, cognition,

logic: true vs. false)

B. Feeling (this type makes value judgments:

good/bad, pleasant/unpleasant).

C. Sensation (this type experiences the

world

through the senses)

D. Intuition (this type "perceives through

his or her unconscious")

An introvert's or an extravert's primary function can be any of these four, and he or she can (and ideally will) develop the others too. Also, introversion and extraversion are merely categories, not destiny, and any given individual can develop opposite traits, and ideally will do so.

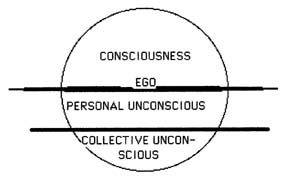

Jung's Psychology of the Unconscious

While Freud believed in the personal unconscious, Jung, once an associate of Freud, accepted the concept of the personal unconscious but also postulated the concept of the collective unconscious. In it are the archetypes, tendencies to form universal images--archetypal images; these can be images of animals, people, anthropomorphic beings (such as the vampire or gods and goddesses), objects (a tree, a house, a cross or a mandala, for example), abstract ideas (made concrete by the images), and patterns such as the hero's journey, as in Joseph Campbell's Hero With a Thousand Faces.

Probably the central therapeutic concept of Jung's analytical psychology is the concept of the need for balance to gain psychic health. Therefore, when an individual is troubled, he or she will dream archetypal, as opposed to merely personal, dreams whose aim is to right an imbalance in the psyche of that individual. This is the concept of compensation. Just as dreams can be personal or archetypal, so can literature. Jung calls the former psychological (it springs from the personal unconscious) and the latter visionary (it springs from the collective unconscious). Visionary literature compensates for collective psychic imbalance.

The collective unconscious is common to the human race the world over. To achieve psychic health, or wholeness, the aim is individuation, becoming a whole, individual person. This process is different for each person (and most never achieve it or even attempt it), but Jung believed it especially involved coming to terms with the following archetypes: the shadow, the anima or animus, and the Self. Archetypes come from the collective unconscious and by definition can be positive and negative. In theory their numbers are limitless.

As a Jungian literary critic, I have searched for "new" archetypes (ones not thought of before, such as the archetype of Ideal Love I refer to in my book, The Stuff That Dreams Are Made On, p. 49) and new ways of looking at well-known archetypes (for example, the concept of the "male" anima; see my essay on Oscar Wilde's fairy tales, link below). Also, I try to look for archetypes in literature that may not have been noticed before, such as shamanism in the poetry of Emily Dickinson (you can link to my essay on this topic below). For more on using Jung to analyze literature, see my book and the links below.

A Diagram of Jungian Psychology

LEVELS OF CONSCIOUSNESS:

A. Individual (includes Ego, Persona, Personality

Types (Introversion or Extraversion, terms Jung coined), and Functions

of Consciousness (Thinking, Feeling, Intuition, Sensation)

B. Family

C. Clan

D. Nation

E. Large group (e. g., The West, Asia, Africa, etc.). The archetypes

from this level are much the same in any individual who comes from that

group.

F. Primeval ancestors. This level applies to all humanity.

G. Animal ancestors in general. This level applies to all higher forms

of life.

H. Central Fire (life itself). ("A spark from this fire ascends through

all intervening levels into every living creature" (Barbara Hannah, Jung:

His Life and Work (Boston: Shambhala, 1991), p. 16).

Hannah notes that with the layer or level of the nation considerable

differences in archetypal images appear--hence the difficulty of

differing

nations in understanding each other. Only the individual and the family

are fully in the conscious sphere, yet elements from these will become

buried in the personal unconscious, much as Freud postulated.

Some Archetypal

Images, Themes, and Symbols

Archetypes, it

is important to remember, are bipolar. They always contain the

potential for the opposite of their central characteristic. If

they are conceived of as positive, the negative is a possibility as

well. Even the shadow,

generally a negative archetypal figure of the same gender as the

individual (containing traits he or she does not or prefers not to

acknowledge), can be a positive force (see Snider, pp. 3 and 15).

Also, archetypes overlap, so that, for instance, the scapegoat may also be a hero or a vampire could be a trickster. I have put the

archetypal images, themes, and symbols in boldface.

Archetypal

Characters

The Hero.

Lord Raglan, in The Hero: A Study in

Tradition, Myth, and Dream, finds that traditionally the hero's

mother is a virgin, the circumstances of his conception are unusual,

and at birth some attempt is made to kill him. He is, however,

carried away and raised by foster parents. We know little or

nothing of his childhood, but when he reaches manhood he returns to his

future kingdom. After a victory over the king or a wild beast, he

marries a princess, becomes king, reigns uneventfully, but later loses

favor with the gods. He is then driven from the city and meets a

mysterious death, often at the top of a hill. There are many

variations on this pattern, of course. The dying and reviving god

of fertility is one of them. See the patterns

demonstrated by Joseph Campbell in

Hero

With a Thousand Faces. The

Feminine Hero is not as prominent in Western culture, but

examples of

both male and female heroes exist throughout the world, examples such

as Gilgamesh, Ishtar, Osiris, Shiva, Krishna, Kali, Oedipus, Theseus,

Perseus, Jason, Dionysus, Orpheus, Diana, Moses, Joseph, Elijah, Jesus,

the

Virgin Mary, Arthur, Merlin, Robin Hood, Joan of Arc, Quetzalcoatl, and

many, many

others.

The hero often has a helper of some sort, perhaps a Wise Old Man or Wise Old Woman who guides him or her (or, conversely, leads him or her astray) and/or a companion, who may be a double (see below) for him or her. Examples of the former include Tiresias (for Oedipus), Merlin (for Arthur), and Naomi (for Ruth); see Snider, pp. 21 and 29. Examples of the latter include Gilgamesh and Enkidu, David and Jonathan, Achilles and Patroclus, Alexander and Hephaestion, Sam and Frodo in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, and many others. Like all archetypes, the double can be both positive and negative. A form of the double used in formal literature is the foil, who provides a contrast with the hero, as does Laertes for Hamlet. Horatio is positive compared to the more negative Laertes.

A modern variation of this

archetype is the Antihero,

found in many forms of literature, from Byron's Don Juan to Hardy's Jude the Obscure to Knowles's A Separate Peace and Lowry's Under the Volcano. A psychological explanation

for the appearance of this archetype in the last two hundred years or

so is the partial disappearance of what Jung called the imago Dei

or the God Image, "imprinted

on the human soul [according to "the Church Fathers"]. When such

an image is spontaneously produced in dreams, fantasies, vision, etc.,

it is, from the psychological point of view, a symbol of the Self . . .

of psychic wholeness" (qtd. in Snider, The Stuff That Dreams Are Made On,

p. 21). The need of a spiritual center filled by an imago Dei or

some Higher or Supreme Power seems

to be

innate in humans, and heroes are often the incarnation of this

archetype. The alcoholic protagonist of Under the Volcano, on the other

hand, desperately needs some spiritual fulfillment such as that

provided by the imago

Dei.

The

Scapegoat can also be a hero,

an outcast or outsider, and a wanderer (e.g., Cain, Oedipus, the

Wandering

Jew, and Coleridge's Ancient Mariner). He or she is conceived as

the alien other. The

scapegoat is an animal

or more usually a human whose death in a public ceremony or expulsion

from the community expiates some taint or sin, the results of which

have been visited upon the community. In ancient times the

sacrifice of the scapegoat was meant to restore fertility to the land,

so that the scapegoat can be a kind of hero.

Scapegoating can also be intensely

personal

in the form of persecution by one individual against another. To

use another as a scapegoat is to project one's shadow (or the

collective shadow)

onto him or her or onto a group. The scapegoats are viewed as

aliens. As Jungian psychoanalyst Erich Neumann writes: "Inside a

nation, the aliens who provide the objects for this projection [of

evil] are the minorities" (Depth

Psychology and a New Ethic, Boston: Shambhala, 1990, p

52). Such minorities include, but are not limited to, "heretics

[i.e., religious minorities], political opponents and national

enemies," and the "fight against . . . [them] is actually the fight

against our own religious doubts, the insecurity of our own political

position, and the one-sidedness of our own national viewpoint" (p.

52). Hence, homophobia, defined by Robert Goss as "the

socialized state of fear, threat, aversion, prejudice, and irrational

hatred of the feelings of same-sex attraction" (Jesus Acted Up: A Gay and Lesbian Manifesto,

New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993, p. 1), is actually a fear of

one's own "feelings of same-sex attraction." Racism,

anti-Semitism, and sexism (and any other kind of prejudice against an

individual because of his or her status)

also involve projecting one's shadow onto the other so that whatever

faults one attributes to the scapegoat are likely to be unpalatable

faults of one's own.

The

Devil Figure is a form of the shadow,

evil incarnate, a figure who frequently offers the hero (or the

individual protagonist in a myth, poem, or story) worldly goods, fame,

or knowledge for possession of his soul. The Faust legend is an

obvious example, as is Wilde's The

Picture of Dorian Gray, in which the protagonist is offered

eternal youth and beauty, however obliquely.

The

Fool is a shadow figure distressed by some unconscious lack of power, often driven by greed or an inordinate desire for fame (all archetypes), who projects

his or her inadequacies against scapegoats as described above.

Modern examples range from political leaders with real power (such as Hitler and Stalin or current leaders from

various parts of the globe, including the United States) to some

(certainly not all) political commentators, leaders of crusades against

minorities, and religious leaders who are intolerant of the other as described above and/or take

financial and spiritual advantage of their followers because of their

greed and desire for power. Probably the most famous literary

example of the latter is Sinclair Lewis's Elmer Gantry, but channel surfing

the TV or radio and doing an Internet search will easily provide more

contemporary examples of all the fools I cite. These fools or tricksters (see below) generally

suffer from psychic "inflation" (see Snider, pp. 80 and 84, n. 5); they

are unconsciously possessed by archetypal forces or figures that drive

them to compensate for their psychic split by persecuting others.

When such figures have real power, it goes without saying they can and

do cause real harm against their own people and especially against

others whom they demonize as the enemy.*

Most wars involve this kind of psychology on the part of those who lead

their nations to war. War

and Peace are powerful

archetypes.

The

Fool is not always negative, of course. A relatively

benevolent form of the fool is the Clown,

who is more aware of his or her trickster aspect, perhaps, than is the

fool. Indeed, laughter can be a great healing force. That

cruelty is often a part of comedy demonstrates a need to displace our

own shadow urges to be cruel. The clown is cruel, or suffers

cruelty, for us. The trickster

often plays this role, for the trickster and the fool or the clown

usually embody the same archetype.

* * *

The

Anima (the feminine side of a man's psyche) can take many forms,

from the merely physical to the highest spirituality and wisdom (see

Snider, p. 17). She can be the Kore

figure (mother/maiden/hag), the Earth

Mother (symbol of fruition, abundance, fertility, but also of

destruction on a grand scale), the

temptress (or femme fatale), the

unfaithful wife or mate, the star-crossed lover, the jilted lover, and so on. See

Erich Neumann's The Great Mother: An

Analysis of the Archetype.

The

Mother and Child together and separately are powerful

archetypes, as are the Father and

Child. Jung says that "'Child'

means something evolving towards independence" (qtd. in Snider, p.

115). The Mother in her

positive aspect is nurturing, protecting, and loving; in her negative

aspect she is withholding of nurture, protection, and love. The Father, too, is protective,

instructive, and

loving in his positive aspect but destructive and hurtful in his

negative aspect. At their best, the mother and the father serve as teachers and

examples of love and acceptance to their children.

There are also the Oedipus and the Electra Complexes for men and women

respectively. Though commonly associated with Freudian theory,

these archetypes are not incompatible with Jungian theory.

The

Animus (the masculine side of a woman's psyche) can also take

many forms, including the merely physical to the highest spirituality

and wisdom (see Snider, p. 18). Whereas the number of wholeness

for a woman, according to Jung, is more often three, for a man is it

four. The animus can also be the tempter

(the rapist is an extreme

example), an homme

fatale, an unfaithful husband

or mate, the star-crossed lover, the jilted lover, and so on.

For the homosexual man, Robert

Hopcke posits

the

possibility of a "male anima"

who functions exactly as the anima has

always

functioned, as "guide to the unconscious and to relatedness with

others,"

and who, again like the traditional anima, is "a figure of often

enormous

erotic charge, all too frequently idealized and projected out onto a

man's

object of love" (Men's Dreams, Men's

Healing, Boston:

Shambhala,

1990, p. 122). Presumably, the "female

animus" can do the same for the lesbian,

although I have not found research on this topic to date.

Another archetype that can apply to

all sexual orientations, although usually it is of the same gender as

the individual, is the Double,

which in Plato's Symposium is

a symbol for male and female same-sex wholeness, as well as for

opposite-sex wholeness. (See Mitchell Walker's "The Double, an

Archetypal Configuration," Spring

(1976): 165-175.) Included in examples of this archetype are

brothers or sisters (often twins), friends, and lovers. To the

examples I cite above in my paragraph on the hero's helper, I would add the Sufi

poet, Rumi, and Shams al-Din.

A

variation of the double archetype

is the puer aeternus (the

eternal youth)

and the senex

(the old man,

often the Wise Old Man, see

Snider, pp. 77-78) and their feminine counterparts, the puella aeternus

and the Wise Old Woman.

These can form

a constellation of the Self,

the archetype of Wholeness,

just as the anima and the animus can lead to such psychic

wholeness. An example of the negative

double is the hostile

brothers (e.g., Cain and Abel); sibling rivalry is

another, often milder, form of this aspect of the archetype.

The

Hermaphrodite, joining the opposites of male/female, is a symbol

of psychic wholeness (see Snider, pp. 20-21). The transgendered

(as well as the bisexual) figure, although not quite the same as the

hermaphrodite, could symbolize wholeness as well, depending on the

context in which it is found. Androgyny,

as I show in my discussion of Virginia Woolf's Orlando

(Snider, pp. 87-93), can also symbolize psychic wholeness, or the Self. Among native Americans

in the Western Hemisphere, the "two-spirit"

third and fourth gender person fits this archetype.

The

Trickster, Jung says, is an aspect of the shadow archetype, at

least in its negative traits (see "On the Psychology of the

Trickster-Figure" in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious.

2nd ed. Trans. R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton

UP,

1969. Vol. 9, part i, of The Collected Works

of C. G. Jung, pp. 255-272, as well as my articles on

Wilde's

The

Importance of Being Earnest and on the trickster in Edward Lear). The trickster, obviously,

deceives, often playfully, sometimes painfully. A very sexual

archetype, it has the ability to change genders and play havoc with the

hyper-rational personality and community. Examples of the

trickster are Satan, Loki, and, in Native American mythology, the

coyote, the raven, and the Winnebago trickster. The vampire is,

in fact, a kind of trickster,

"able

to change into many shapes, among them bats, wolves, spiders,

butterflies,

fog, or even a bit of straw" (see my essay on "The

Vampire Archetype in Charlotte and Emily

Brontë").

A necessary archetype is the Healer, be he or she a spiritual

figure (such as a shaman or priest), a physician, or, indeed, a

psychotherapist. One example is the curandera in Rudolfo Anaya's Bless

Me, Ultima. Sadly, people who need healing, whether

spiritually or physically or both, sometimes seek help from charlatans, who are actually

tricksters of a very malignant order. Because the need for

wholeness is so strong, sometimes even these charlatans can be

effective.

Other powerful healing archetypes

are confession and forgiveness.

The

Persona, though intimately tied to the psychology of the

conscious mind, can also be an archetype. It is the role we play

at any given time. The psychological danger is to identify too

closely with one particular role (see Snider, p. 9).

* * *

Archetypal

Concepts and Themes

The

Platonic Ideal is a source of inspiration and a spiritual ideal

for the individual (or protagonist in myth and literature). It is

an intellectual or a spiritual rather than a physical attraction.

The

Quest can be a search for virtually anything, noble or

ignoble, spiritual or physical; in any case, the goal (also called the treasure hard to obtain) has great

value

for the quester.

The

Task is something that must be done to achieve something

valuable:

the hero must perform this task to save the kingdom, win the fair lady,

etc.

Initiation

involves going from one stage of life to another. Typically

performed or

experienced by a young person, it can also occur during any stage of

life,

as in the James Dickey novel, Deliverance.

The proverbial mid-life crisis,

if successful, is a kind of initiation.

The Journey can combine

all or some of the above. Indeed, the individuation process (see above) is

a kind of journey.

The Fall involves going

from a higher

to a lower state of being, as in Paradise

Lost, Sister Carrie, The

Great Gatsby, or The Mayor

of Casterbridge.

The

hieros gamos

("sacred wedding") or coniunctio can symbolize the

union of opposites that is achieved in the Self (see Snider, p. 20).

Death

and Rebirth. The most common of all situational

archetypes,

death and rebirth grows out of the parallel between the cycle of nature

and the cycle of

life. Life and Death are themselves archetypes

everyone experiences.

Archetypal Symbols

These are too many even to begin to be comprehensive, but here are a few (and this is not to say the images and themes above are not symbolic; they are).

The

Mandala, a circle, often squared, can also symbolize the

wholeness of the Self or the

yearning for such wholeness.

Light/Darkness

(the conscious and the unconscious), Water or wetness/Dryness or the desert,

Heaven/Hell, Trees, Rocks, Dirt, Flowers, Animals of all

kinds (insects, birds, fish, mammals), etc., etc. Birds,

for instance, often symbolize the spirit (e.g., the Holy Spirit as a

dove), but could symbolize many other things, as, for example, fear and

destruction (e.g., in the Hitchcock movie, The Birds), courage, wisdom,

etc. For many American Indians, the eagle is a particularly

sacred symbol. By definition, a symbol

has an infinitive number of possible meanings. The trickster, as I point out above,

often appears as an animal, as does the vampire.

Caves

can symbolize the unconscious, as can bodies

of water, the forest, night, the moon, etc. These tend to be

feminine symbols as well, just as anything that encloses or nourishes,

depending on the context, can be a

feminine symbol.

In addition to light, the sky, the sun, the eyes, etc., can symbolize

consciousness.

A

seascape or the sea itself can symbolize many

things, as in Melville's Moby Dick or

Annie Proulx's The Shipping News.

Similarly, in Proulx's story, "Brokeback Mountain," as well in the

movie based on the story, the landscape

is a powerful symbol standing for the relationship of Jack and Ennis

and for many other things.

Although, as Freud is said to have

remarked,

sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, sometimes it is indeed a phallic symbol, as are other items,

depending on the context, whose lengths are much longer than their

widths.

The meaning of any of the above archetypal

characters, concepts, themes, and symbols depends on the context in

which they are found, be it an individual's dreams, life and psyche or

a given myth, fairy tale, piece of art, literature or whatever.

The context is vital if any real

meaning is to be attached to the

archetypes.

- Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary

See also Snider, The

Stuff

That

Dreams Are Made On: A Jungian Interpretation of Literature.

Top.

For some of my essays using Jungian psychology to analyze literature

see:

Read about my novels, Wrestling

with Angels: A Tale of Two Brothers, Bare

Roots, and Loud Whisper.

Links: C. G.

Jung Page.

Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender

Criticism.