Charles Lutwidge Dodgson's drawing for The Rectory Umbrella (c. 1849-50).

"'Everything is Queer To-day': Lewis Carroll's

Alice Through the

Jungian Looking-Glass," Clifton Snider

"Everything is Queer To-day":

Lewis Carroll’s

Alice Through the Jungian Looking-Glass

I

Of all Victorian children’s stories that are

enjoyed equally by children and adults, none is more popular than Lewis

Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through

the Looking-Glass (1872).1 More than any other piece of

literature written for children during the Victorian period, Alice

in Wonderland (as the tales together are generally called) has

spawned a seemingly never-ending academic industry; and, although

Carroll also wrote other children’s books (The Hunting of the Snark

(1876) and the Sylvie and Bruno books (1889 and 1893) are the

most notable), the interest in the Alice books far outweighs the

interest in the other books. Alice in Wonderland has been

analyzed from virtually all critical points of view.2 The

Freudian approach has been applied many times, starting at least as

early as 1933 with a piece by A. M. E. Goldschmidt (see Phillips, Aspects

of Alice 279-82). Carroll himself receives the Freudian treatment

in Phyllis Greenacre’s Swift and Carroll: A Psychoanalytic Study of

Two Lives (1955). The Jungian approach, too, has been tried on

Alice in an article called “Alice as Anima : The Image of Woman

in Carroll’s Classic,” published in Aspects of Alice .

Although much that Judith Bloomingdale says is on the mark, she is not

convincing in making Alice the anima. Alice may be, for Carroll, an

incipient image of the anima, but she is far more, as Bloomingdale

herself demonstrates and as I hope my own analysis will

show.3

One Freudian critic goes so far as to declare:

“It is impossible to gain conscious understanding of the life of Lewis

Carroll or of the meaning of his written fantasy unless a

psychoanalytic approach is used” (Skinner 293). Although much nonsense

has been written using the psychoanalytic approach, the approach itself

is valid. At the same time, it leaves many psychological issues

unexplored. In “The Spiritual Problem of Modern Man,” Jung writes: “If

anything of importance is devalued in our conscious life, and

perishes--so runs the law--there arises a compensation in the

unconscious” (86). Jungian criticism attempts to account for the

collective appeal of a classic like Alice in Wonderland. It

asks, For what that is lacking in the contemporary collective psyche

does the work compensate? An account for such appeal or compensation

cannot be entirely provided by an examination of the author’s life,

however provocative and interesting that life is--and Carroll’s life is

certainly an interesting case study. First generation Jungians like

Marie-Louise von Franz (in Puer Aeternus ) and Barbara Hannah

(in Striving Towards Wholeness ) do examine in tandem the lives

and works of literary artists, but Jung himself warned against the

“reduction of art to personal factors.” Such a reduction “deflects our

attention from the psychology of the work of art and focuses it on the

psychology of the artist . . . the work of art exists in its own right

and cannot be got rid of by changing it into a personal complex”

(“Psychology and Literature” 93). In other words, the work of art is

independent of and greater than its creator. It may tell us much about

the artist, but ultimately, if it is to endure, its appeal must be

collective--“visionary,” to use Jung’s term (ibid. 89).

Having said this, I must add that a brief

examination of Carroll’s life can provide clues as to how he was

uniquely suited to produce his classic. Like Edward Lear, Carroll

in some respects fits the profile of the puer aeternus as

outlined by von Franz in Puer Aeternus. He seems to have had a

mother complex; further, as one Carroll scholar states, he had a

“reluctance to commit himself, to become in any way tied down”

(Gattégno 215), and this is another puer trait. As a puer

aeternus, Carroll had “a certain kind of spirituality which comes

from a relatively close contact with the collective unconscious” (von

Franz 4); Carroll was ordained a deacon, albeit he never became a

priest.

Stephen Prickett points out some surface similarities between Lear and Carroll:

Both were

shy and sensitive bachelors; both were afraid of dogs;

both were of

an ‘analytic state of mind’--Carroll indexed his

entire

correspondence, which, by his death had 98,000 cross-

references.

Both were marginal kinds of men, if in very different

senses. (130)

Like many of the authors whose work I have examined, both Lear and Carroll are social outsiders. Although both shared some of the same friends (among them some of the Pre-Raphaelites and the Tennysons), no one has found any record of either man referring to the other, though both pioneered the nonsense genre.4 Both were visual artists. Carroll’s photography and drawing were avocations, whereas Lear’s paintings provided his livelihood and he illustrated his own books, as Carroll did not. Unlike Lear and the typical puer, Carroll hardly ever traveled abroad (he made one trip to the Continent in his lifetime). And he was different from the typical puer as described by von Franz in that he was neither a homosexual, so far as we know, nor a Don Juan.

Lear was a homosexual. Carroll, on the

other hand, was a heterosexual pedophile who “collected” little girls

like so many dolls and who lost his stammer in their presence. A famous

photographer, Carroll abruptly gave up photography in 1880 after having

practiced the art for some twenty-four years. He gave no explanation,

but one reason may have been gossip about and resistance to his

photographing pre-pubescent girls in the nude. After 1880 he continued

drawing them in the nude (Clark 208). His nephew and first biographer,

Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, records that Carroll “always took about

with him a stock of puzzles when he travelled, to amuse any little

[female] companions [he detested little boys] whom chance might send

him” (407). To pretend that Carroll’s predilections were not in part

sexual is extremely naïve (see Gattégno 82 and Greenacre

245-46).

Carroll’s sexual orientation provided a powerful

motive for his creative work. His remaining child-like as an adult also

gave him entrée into the psyche of the child. Moreover, he had,

like Lear, a nature somewhat akin to the Native American berdache. In

his inventions of puzzles, riddles, and games, in his visual art, in

his appeal to children, and indeed in his name-giving function (both

for himself and for such characters as Jabberwocky and the

Bandersnatch), Carroll fulfilled the role of the berdache. The adult

Carroll disapproved of “transvestite parts [in the theater], though

only when it involved a man’s being dressed as a woman”

(Gattégno 226), but at about the age of seventeen or eighteen he

drew a curious picture as the frontispiece to a family magazine called The

Rectory. The Rectory Umbrella shows a bearded man with an

almost Cheshire-cat grin lying down on one elbow. He is dressed, as

Greenacre points out, as “a little girl, the skirt suggesting the

appearance of a closed umbrella” (131). He’s holding an umbrella on

which are the words “Tales, Poetry, Fun, Riddles, Jokes.” Overhead, six

little sexless imps are trying to rain down chunks of “Woe, Spite,

Ennui, Gloom, Crossness, and Alloverishness.” Rushing through the air

and to the safety under the umbrella are seven female fairies bringing

“Liveliness, Knowledge, Good Humour, Taste, Cheerfulness, Content, and

Mirth” (Greenacre 130-31). The cross-dressed man’s resemblance to the

berdache in this drawing is striking, all the more so because it is no

doubt unconscious.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson's drawing for The Rectory Umbrella (c. 1849-50).

In physical appearance Carroll resembled a

berdache far more than did Lear, who wore glasses and had a great

Victorian beard. Not only was Carroll clean-shaven, but also, Greenacre

writes, “As he grew older, his face became more feminine in cast, an

effect possibly enhanced by his wearing his hair rather long. His

effeminacy was sufficiently obvious that some of his less sympathetic

students once wrote a parody of his parodies and signed it ‘Louisa

Caroline’” (166) Although Greenacre believes “there is no expression of

frustrated paternity in” Carroll, as a child “there was something of a

motherly or older sisterly quality in his care for and entertainment of

the young children” in his family. Furthermore,

there was a

slightly feminine cast to his charming thoughtfulness

--his interest

in tiny things, his patient arrangements of puppet

theatricals,

and his protectiveness toward small animals as well

as small

sisters. (222)

It is possible the young Lewis Carroll exhibited so-called feminine

traits even earlier, like the famous Zuni berdache We’Wha (Roscoe 33).

Greenacre believes “Charles . . . had much in his nature that suggests

the Victorian woman” (222-23). And Camille Paglia declares: “Carroll’s

spiritual identity was thoroughly feminine” (547). Furthermore, Paglia

says, “Carroll’s Alice books introduced an epicene element into

English discourse that . . . flourishes to this day” (549). It seems

clear that in his personal appearance, in his personality and psyche,

in his persona as a writer of nonsense books, and in the books

themselves, Carroll fits the archetype of the berdache.

Carroll also fits the archetype of the Trickster, which I’ve discussed at length in my article on Lear. Karl Kerényi writes in his commentary on Paul Radin’s study of the Winnebago Trickster cycle that the Trickster “could be defined as the timeless root of all picaresque creations of world literature” (176), and what are the Alice books if not picaresque?

There is another figure in the myths of some Pueblo Indians that resembles Lewis Carroll--Thinking Woman. In his Pueblo Gods and Myths , Hamilton A. Tyler quotes nineteenth-century anthropologist John M. Gunn, who wrote a book about the Acoma and Laguna Pueblos, on Thinking-Woman: “Their theory is that reason (personified) is the supreme power, a master mind that has always existed, which they call Sitch-tche-na-ko. This is the feminine form for thought or reason” (qtd. by Tyler 90-91). Another anthropologist, L. A. White, reports that at the Santa Ana Pueblo Thinking Woman’s “function was to scheme or plan,” and that an Acoma Indian said, “She must have been quite small, for she sat on Iatiku’s [the Corn-Mother’s] right shoulder during her contests with her sister and told her what to do” (qtd. by Tyler 91). The form she takes is that of a spider. One cannot help but be reminded of the Gnat in Through The Looking-Glass, which William Empson believes “gives a touching picture of Dodgson” himself (274). The Gnat tries to help Alice develop a sense of humor: “‘That’s a joke. I wish you had made it,’” he tells her (Oxford Alice 155; all references to the Alice books are to this edition). Here the Gnat exhibits a Trickster trait--an attempt to bring humor to the serious little girl. Like Thinking Woman, Carroll excelled in reason, even as he spun out so-called nonsense tales for children. Significantly, in Western culture thinking has been designated a “masculine” function, yet here it is embodied in a rather androgynous storyteller, the protagonist of whose tale is a little girl.

Then there is the matter of the storyteller’s

name. Many critics and scholars make the point that there were really

two men.5 One was named Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. He was the

oldest son (and third child) in a family of eleven (seven girls, four

boys), whose father was himself a clergyman. Born in Daresbury (in

Cheshire) on 27 January 1832, Dodgson had a happy childhood until he

was sent to Rugby. There, although he did well in his studies, he was

bullied and miserable. His experience at Rugby probably began his

hatred of little boys, which got worse as he grew into middle age.

Shortly after he entered Christ Church, Oxford, at the age of nineteen,

his mother died. One biographer remarks that Dodgson “was profoundly

affected by his mother’s death,” although he tended to hide his

feelings (Clark 66; another scholar, I should note, disagrees. Humphrey

Carpenter declares: “it is very striking how little impression

Dodgson’s mother’s death seems to have made on him,” 47). He lived at

Oxford the remainder of his life (till, that is, 14 January 1898),

becoming a “Student” (the Christ Church term for “Fellow”) and a

lecturer in mathematics (until 1881). Under the name of Dodgson he

published works on mathematics and logic.

In 1856 Edmund Yates, editor of The Train,

a small magazine in which Dodgson had published some poetry, chose

the pseudonym Lewis Carroll from a list of four submitted by Dodgson.

The name is a reversal and variation of Charles Lutwidge

(Gattégno 229). It was, of course, as Lewis Carroll that the

shy, stammering Oxford lecturer became famous as the author of Alice’s

Adventures in Wonderland and other stories for children. Had Lewis

Carroll not possessed the unique psyche I’ve outlined, had he not

become friends with the four Liddell children (Harry, Lorina, Alice,

and Edith, children of the Dean of Christ Church), had he not fallen in

love with Alice, and had Alice not urged him to write down the stories

he told the children, the world probably would never have become

acquainted with Alice in Wonderland . All artists who produce

visionary work--work stemming from the collective unconscious--have a

particular psychological makeup or complex that allows them to produce

such work. Only a person with the Dodgson/Carroll psyche writing in the

Victorian age could have produced the Alice books. I quite agree with

Derek Hudson that “Alice in Wonderland owes its unique place in

our literature to the fact that it was the work of a unique genius,

that of a mathematician and logician who was also a humorist and a

poet” (128). What accounts for its wide and lasting collective appeal

is what I intend to examine in the following pages.

II

William Empson comments: “Wonderland is a

dream, but the Looking-Glass is self-conscious” (257). While I

agree, nevertheless, both are cast as dreams, and indeed the question

of dreams, who’s dreaming what, is Alice only “a sort of thing” in the

Red King’s dreams (Oxford Alice 168), is important to both

books. At the end of Looking-Glass, Alice shakes the Red

Queen into her own kitten. She questions the kitten:

“Now,

Kitty, let’s consider who it was that dreamed it all.

. . . You see,

Kitty, it must have been either me or the Red King.

He was part of

my dream, of course--but then I was part of his

dream, too! Was

it the Red King, Kitty?” (ibid. 244)

And the first-person narrator--far more prominent in Looking-Glass than in Wonderland --leaves the answer up to the reader: “Which do you think it was?” The book ends with the same dream motif in an acrostic poem based on Alice Liddell’s name: Alice Pleasance Liddell. I quote the last three stanzas:

Children

yet, the tale to hear,

Eager eye and

willing ear,

Lovingly shall

nestle near.

In a

Wonderland they lie,

Dreaming as

the days go by,

Dreaming as

the summers die:

Ever drifting

down the stream--

Lingering in

the golden gleam--

Life, what is

it but a dream?6 (Ibid. 245)

One is reminded here of Poe’s poetic question “Is all that

we see or seem/But a dream within a dream?” (10). Jung himself

observes:

III

Of the other talking animals and characters, some of the most important are the Caterpillar, the King and Queen of Hearts, Tweedledum and Tweedledee, Humpty Dumpty, the White Knight, and the Red and White Queens. The dance is another important symbol; so is language itself, the garden, and eating and drinking. But perhaps the most prominent symbol is the cat in its various forms. The Caterpillar, like the pool of tears, requires little explanation. They are both elements of the archetype of transformation. Alice has a symbolic baptism in the tears, a symbolic death. The caterpillar also symbolizes death and rebirth. Judith Bloomingdale is correct to compare the Duchess and the Queen of Hearts with Kali, the Hindu goddess in her terrible aspect (Bloomingdale 386). Alice herself has the potential for being destructive (her shadow side); she must learn to recognize this potential and accommodate it. While the King of Hearts presides over the trial of the Knave of Hearts, the Queen has the real power (or, better, surreal power--for in this nonsense world she never exercises her power). Her continual commands, “Off with his head,” “Off with her head,” “Off with their heads,” show her lack of Eros and threaten Alice’s new consciousness shown in the development of the Logos principle in her.

In Tweedledum and Tweedledee the twin motif found in most mythologies is represented (see Cirlot 355-56 and Roscoe 218). In their ritualized, crazy personal combat, they are a parody of the hostile brothers motif--another attack on patriarchal mythological tradition. The amusing sub-standard dialect they use suggests their primal roots:

“I know what you’re thinking about,” said Tweedledum;

“but it isn’t

so, nohow.”

“Contrariwise,” continued Tweedledee, “if it was so,

it

might be; and

if it were so, it would be; but as it isn’t, it ain’t.

That’s logic.”

(Oxford Alice 160)

Alice is more interested in finding her way out of the woods and to

the garden than in talking logic with the twin brothers. But she must

learn from them before she can continue. The first lesson is how to

begin a visit: by saying “‘How d’ye do?’” (ibid.).

More importantly, she participates in a dance

with them, “dancing round in a ring” under a tree (ibid. 161). Whereas

in Wonderland Alice had merely watched the Lobster-Quadrille

(ibid. 90), in Looking-Glass she participates in the dance--an

indication of her psychic growth. Even though Carroll consciously keeps

religion out of the Alice stories, here he includes one of the most

ancient of humankind’s sacred rites. The dance symbolizes, among many

things, “a series of dissolutions and rebirths . . . the ‘Great Change’

[of creation] . . . the measure of man’s achievement is his adjustment,

without fear, to the universal circumstance of change” (Wosien, Sacred

Dance 10). One of Alice’s tasks in Wonderland and the Looking-Glass

world is to adjust to radical change. “The earliest view of time,”

writes Maria-Gabriele Wosien, “was cyclic, not linear. . . . Life, from

the very first, is bound up with transformation” (ibid.). Time in

Carroll’s world is hardly linear (the Red Queen teaches Alice that “here

. . . it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same

place,” Oxford Alice 145); and transformation is one of the key

archetypes.11 It is no accident that the dance Alice

participates in takes the circular shape of the mandala, a supreme

symbol of wholeness. In the dance there is an order lacking in the

anarchy of the mad tea-party, the Queen of Heart’s croquet-ground, and

her court.12

Humpty Dumpty, the White Knight, the Red and

White Queens,--all are instructors, helpers, or guides to the

heroine--Wise Old Men and Women, as it were. Except in this nonsense

underworld everything is turned around, so that, for instance, Alice

ends up helping the White Knight as he keeps falling down, head first.

(He does teach Alice, albeit by negative example.) Although

Cirlot notes that the alchemists believed the egg “was the container

for matter and for thought” (94), Humpty Dumpty is a parody of

masculine pride in his intellectual powers. For all his humorous

arrogance about knowing the meanings of words, the Eros principle of

relatedness is almost totally lacking in him--he doubts he would

recognize Alice if he saw her again. He illustrates what Jung refers to

as “the law of independence inherent in the thinking function and . . .

its emancipation from the concretism of sensuous perceptions” (“Psychic

Conflicts in a Child” 34). Still, he is egg-shaped and has

grown from an egg into a real character, so he also symbolizes the

possibility of psychic growth. The Red and White Queens are like two

haughty but harmless children who talk “dreadful nonsense” with Alice

(Oxford Alice 227). They show, by contrast, Alice’s new

self-confidence and maturity. Humpty Dumpty, the White Knight, the Red

and White Queens,--each is in fact a parody of the Wise Old Man or the

Wise Old Woman.

Language itself is symbolic in Alice in Wonderland. W. H. Auden goes so far as to maintain that “one of the most important and powerful characters [in the Alice books] is not a person but the English language” (9). The Word, the Logos, is prominent in so many ways--among them puns, riddles, the concern with meaning--that it would take another essay to discuss them all. Alice, the heroine as opposed to the hero, as I’ve indicated, develops a more complete psyche through her appropriation of the Logos principle.

The garden is another symbol that seems hardly to require analysis. For Bloomingdale, “The garden is . . . a positive mother symbol, no longer wild nature, but cultivated, tended, fostered--in short, the Garden of Live Flowers” (387). Instead of the Edenic garden of innocence, Alice seeks the “civilized,” ordered garden of the familiar world above ground. Ironically, she must go through a hero’s journey (another of the many archetypal motifs in the Alice books) to get there.13 The garden itself stands for wholeness--the uniting of untamed nature with the conscious, controlling hand of human beings.

Also symbolic are eating and drinking--from the

bottle with the label that says “DRINK ME” and the little cake that

says “EAT ME” in Wonderland to Queen Alice’s banquet at the end

of Looking-Glass. Erich Neumann makes the point that “Hunger

and food are the prime movers of mankind. . . . Life=power=food, the

earliest formula for obtaining power over anything, appears in the

oldest of the Pyramid Texts” (27). That eating is power for Alice is

clear when she eats the Caterpillar’s mushroom to control her size. She

is whole (her right size) when she’s able to ascertain the right amount

to eat.

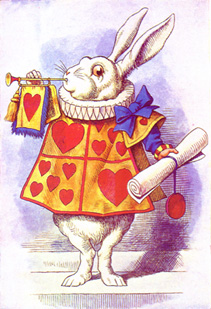

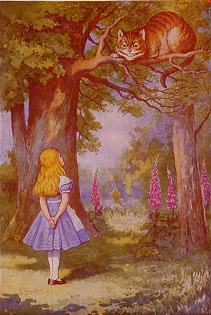

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel.

Notes

1A fairly recent example of the popularity I refer to is an article in National Geographic: “The Wonderland of Lewis Carroll” (June 1991). More recently, yet another film version of the Alice stories (Alice in Wonderland) appeared on the 28th of February 1999 on NBC. Brian Lowry, in the Los Angeles Times, reports: “the three-hour production sank the premiere of Disney’s ‘The Little Mermaid,’ coming through the looking glass with this season’s highest rating for a single-part TV movie . . .” (F11). An exhibit running through 24 May 2006 at the Doheny Memorial Library of the University of Southern California, "The Curious World of Lewis Carroll," coincides with a symposium, "Lewis Carroll and the Idea of Childhood," at the Doheny and at the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, on 31 March and 1 April respectively. Morton N. Cohen deftly summarizes the popularity of the Alice books. He makes the following startling statement: “Along with the Bible and Shakespeare’s works, they [the Alice books] are the most widely quoted books in the Western world” (xxii).

2Three anthologies published within

the last thirty or so years illustrate the variety of studies: Robert

Phillips’ Aspects of Alice: Lewis Carroll’s Dreamchild as seen

through the Critics’ Looking-Glasses, 1865-1971 (1971), Edward

Guiliano’s Lewis Carroll: A Celebration, Essays on the Occasion of

the 150th Anniversary of the Birth of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1982),

and Harold Bloom’s Lewis Carroll (1987), published as part of

the Modern Critical Views series. In the Introduction to his 1995

biography, Cohen summarizes the “eccentric readings” of the Alice

books, which, according to Cohen, include seeing Alice as “a

transvestite Christ,” regarding “Carroll himself as the first

‘acidhead.’ . . . [and] explaining “that the story is about toilet

training and bowel movements” (xxiii).

3Jeffrey Stern also views Alice as

the anima for Carroll, but he confines his comments to a few paragraphs

in the context of his essay, "Lewis Carroll the Pre-Raphaelite"

(165-166).

4Although Carroll’s Alice stories are

usually described as nonsense, unlike Lear’s verse, the issue of genre

is more complex for Carroll. Carroll more than once referred to Alice’s

Adventures in Wonderland as a “fairy-tale” (see Selected

Letters 29 and Diaries 185). The complexity of the issue

Nina Demurova deftly illustrates in her article: “Toward a Definition

of Alice 's Genre: The Folktale and Fairy-tale Connections.”

She concludes:

The

scientific, the nonsensical, the linguistic--one thing is perfectly

clear about

these two

books [Wonderland and Looking-Glass], with their

unexpected

twists and

depths: Carroll’s fairy tales realize in most original and unexpected

forms both

literary and scientific types of perception. And that is why

philosophers,

logicians,

mathematicians, physicists, psychologists, folklorists, politicians, as

well as

literary

critics and armchair readers, all find material for thought and

interpretation in

the Alices.

(86)

Without discounting the other possibilities, I would here classify the Alice books as visionary nonsense--a modern myth.

5Virginia Woolf, in her review of the Nonesuch Press “complete” Lewis Carroll, declares that after reading Alice in Wonderland “we wake to find--is it the Rev. C. L. Dodgson? Is it Lewis Carroll? Or is it both combined?” (83). Greenacre quotes a letter, dated 15 December 1875, “the only letter signed with both names [Lewis Carroll and C. L. Dodgson]. More frequently,” Greenacre adds, “Mr. Dodgson preferred to keep his identity separate from that of Lewis Carroll” (120-21). It was only in the last two months of his life, however, that Dodgson refused to accept mail addressed to Lewis Carroll (Gattégno 231).

6Martin Gardner, in The Annotated Alice, notes: “In this terminal poem, one of Carroll’s best, he recalls that July 4 [1862] boating expedition up the Thames on which he first told the story of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to the three Liddell girls” (345, n. 1).

7Ironically, Carroll seems to have been as prudish as the stereotypical Victorian--despite or perhaps because of his forbidden sexual proclivities (to be sure no one can prove precisely what he did with those proclivities on the genital level). While he found nothing wrong with photographs and drawings of nude children, he would, in Woolf’s words, “produce an extra-Bowdlerised edition of Shakespeare for the use of British maidens” (83).

8Bloomingdale finds the fact that

Alice is a girl significant because “it affirms the androgynous nature

of the presexual self” (383); however, the same is true for any

child who is an archetypal symbol. The fact that Alice is female is

important but for other reasons, as we shall see.

9In Secret Gardens, Humphrey Carpenter makes a strong argument that Alice in Wonderland is actually a “parody of religion” (65). The parody here and Carroll’s later “anguished piety,” Carpenter believes, “spring from the same thing, the fact that Dodgson’s religious beliefs were utterly insecure” (64). I submit that in the Alice books Carroll has in fact compensated for that insecure belief by creating a new myth, one which, as I show below, compensates in a variety of ways for conventional Christianity.

10Hillman cautions against the type of criticism psychoanalysts are prone to: “. . . to consider the dream as an emotional wish costs soul; to mistake the chthonic as the natural loses psyche. We cannot claim to be psychological when we read dream images in terms of drives or desires” (43).

11Apart from the basic transformation in Alice herself, other examples of the archetype are the baby that turns into a pig and the White Queen who turns into a sheep.

12W. H. Auden sees games, too, as an organizing principle against “anarchy and incompetence” (9). The Looking-Glass world, of course, is actually a huge chess board.

13Alice’s train ride and the chess

board moves give a modern context to Alice’s journey.

Works Cited

Auden, W. H. “Today’s ‘Wonder-World’ Needs Alice.” New York Times

Magazine 1 July 1962. Rpt. in Phillips, Robert,

ed. Aspects of Alice:

Lewis Carroll’s Dreamchild as seen Through the

Critics’ Looking- Glasses,

1865-1971. New York: Vanguard, 1971. 3-12.

Auerbach, Nina. “Alice and Wonderland: A Curious Child.” Victorian

Studies (18) 1973. Rpt. in Bloom, Harold, ed. Lewis

Carroll.

New York: Chelsea House, 1987. 31-44.

Bloom, Harold, ed. Lewis Carroll. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

Bloomingdale, Judith. “Alice as Anima : The Image of Woman in Carroll’s