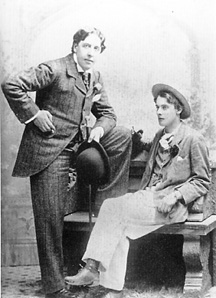

Wilde and Bosie, Oxford, c. 1893

Clifton Snider

English Department, Emeritus

California State University, Long Beach

Oscar Wilde, Queer Addict:

Biography and De Profundis

Although there have always been brave scholarly and creative souls who have dared write about him, Wilde's literary reputation did not begin to rise until about the middle of the twentieth century. Now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, there is an academic industry devoted to Wilde, augmented by the popularity of Queer Studies, one of the most current trends in literary criticism. Commentators as disparate as Arnold Bennett, a fine though seldom-read early-twentieth-century novelist, and W. H. Auden, a giant of twentieth-century poetry, have agreed that The Importance of Being Earnest is his "best work" (Bennett 418), "perhaps the only pure verbal opera in English" (Auden 322). Bennett was completely wrong in his opinion that "Wilde's popular vogue is over" (417), and Auden, right in so many of his opinions on Wilde, was completely wrong to call The Portrait of Mr. W. H. "shy-making" and The Picture of Dorian Gray a "bore" (322). However, reviewing the Rupert Hart-Davis edition of The Letters of Oscar Wilde (1962), Auden is right on the mark when he observes that after prison, Wilde "turned to the only consolations readily available--drink and boys" (319).

Wilde's grandson, Merlin Holland, gives an excellent summary of the history of Wilde as a subject of biography in his article, "Biography and the Art of Lying," published in The Cambridge Companion to Oscar Wilde (1997), and supplemented by his richly-illustrated but brief biography, The Wilde Album (1997). The early recollections by those who knew Wilde were "fragmentary, even impressionistic, and books for the most part alluded to his downfall in veiled terms" ("Biography" 5). Even the indispensable biography by Richard Ellmann contains errors, such as the photo of Wilde in drag as Salomé, which is actually the "Hungarian opera singer Alice Guszalewicz as Salome, Cologne, 1906" ("Biography" 11). Basing his judgment on the latest medical findings, Holland also believes Ellmann is wrong about Wilde having suffered from syphilis (12-13), and I agree with Holland's assessment. As Holland says, "The French doctor who attended Wilde [on his deathbed] and signed the diagnosis, Paul Claisse, had previously written papers on skin disorders, meningitis and tertiary syphilis, all conditions which are alleged to have contributed to his [Wilde's] death" (13). Had Wilde suffered from tertiary syphilis, surely Claisse would have discovered the fact.

Despite the weighty attention Wilde and his work have received, I agree with John Lahr's assertion: "None of Wilde's biographers offer[s] an interpretation of his self-destructiveness [. . .]". Lahr adds, "for that one has to read between the lines of Wilde's wit" (xxxix). Yet, although Lahr cites a few lines of that famous wit, he doesn't begin to analyze Wilde's self-destructiveness. This I intend to do. I suspect biographers and critics have shied away from the subject for a number of reasons: personal friendship with Wilde, self-protection (here the prime example is Lord Alfred Douglas), other aims, lack of knowledge and evidence, and political correctness. Queer critics in particular may not want to sully the reputation of one who is, after all, a gay icon.1 As a queer critic myself, I have no intention of tarring Wilde's reputation in the least. What I intend to do is to uncover some of the reasons for Wilde's self-destructiveness, recognizing, as Wilde says in Intentions, the full truth is "unattainable" (405).

I also recognize and accept Holland's conclusion

that Wilde's life "is simply not a life which can tolerate an either/or

approach with logical conclusions, but demands the flexibility of a

both/and treatment, often raising questions for which there are no

answers" ("Biography" 4). One more caveat: when one writes about

addictions, as I will, one writes about diseases. The issues are

medical and psychological, not moral. The evidence suggests that

Wilde was an alcoholic and a romance addict.2 In

literary studies it is common to find authors who are alcoholic;

indeed, sometimes being alcoholic seems to be a requirement to join the

canon. As Donald W. Goodwin points out, "Of seven [American] Nobel

Prize winners, five were alcoholic" (74).

All joking aside, Wilde as a hard-drinking Irishman might be expected to find the label "alcoholic" applied to him by his biographers routinely, but that has not been the case, perhaps because he was not the kind of alcoholic who literally ended up in the gutter, whether looking at the stars or not. Yet there is evidence that he was, if not an alcoholic in the stereotypical sense, then one who in his post-prison years used alcohol as a way to compensate for the spiritual vacancy he so keenly felt. Even before the débâcle of 1895, there are stories, some by Wilde himself, of his overindulgence in spirits. He liked to tell the story about his experience with the miners of Leadville, Colorado, where he was lowered "in a rickety bucket in which it was impossible to be graceful" into a silver mine in order to have "supper": "the first course being whisky, the second whisky and the third whisky" ("Impressions of America" 10). Around the time A Woman of No Importance was first produced (April 1893), Max Beerbohm wrote to Wilde's close friend, Reggie Turner: "I am sorry to say that Oscar drinks far more than he ought: indeed the first time I saw him, after all that long period of distant adoration and reverence, he was in a hopeless state of intoxication" (qtd. in Hyde, Oscar Wilde 176).

The only biographer that explicitly broaches the

possibility of Wilde's being an alcoholic is Barbara Belford.

Unfortunately she does not provide much evidence. She refrains

from labeling Wilde himself an alcoholic, but does not hesitate to call

his older brother, Willie, "an alcoholic by the standards of denial,

binges, and blackouts" (280). Although Belford claims the "term alcoholism

was not in general use in his [Wilde's] time" (280, emphasis hers),

according to the Oxford English Dictionary, it has been current

in English since at least 1860. The notion of alcoholism as a

disease, according to Goodwin, "originated in the writings of Benjamin

Rush and the British physician Thomas Trotter in the early nineteenth

century and became increasing popular with physicians as the century

progressed" (33).

In his letters, Wilde himself uses the word "alcoholic" at least twice, once as a noun, once as an adjective. Writing to his great friend, Robbie Ross, he refers to another friend nicknamed "Sir John" as being "grand in his cups" (Complete Letters 1118). Writing to Reggie Turner, Wilde calls Sir John "the most good-hearted of the alcoholic" (1121). Finally, rather mysteriously he writes to Ross on 21 March 1899, the year before Wilde's death: "I never dreamed of having [Leonard] Smithers [his publisher] to bring alcoholic experience to bear on my affairs. It was a joke" (1134). Since Smithers himself "is believed to have died of drink and drugs" (Holland and Hart-Davis 919, n. 2), it is impossible to say whether the "alcoholic experience" Wilde refers to is Wilde's or Smithers's. However, since Wilde was perpetually asking for money from Smithers and complaining about the lack of money, it is not unlikely that the "alcoholic experience" is Wilde's. Perhaps Smithers had used an alcoholic episode as an excuse for not sending money.

Wilde is famously quoted as having said, "I have

discovered . . . that alcohol taken in sufficient quantity produces

all the effects of drunkenness" (qtd. in Ellmann 562, n.). He

also enjoyed opium cigarettes. Marcel Schwob, Wilde's friend in Paris,

writes of an 1891 visit: Wilde "never stopped smoking opium-tainted

Egyptian cigarettes. A terrible absinthe-drinker, through which

he got his visions and desires" (qtd. in Ellmann 346). Another

drug he tried was hashish. In January 1895 on a trip to Algiers with

Bosie, both used it, as he wrote to Ross: "it is quite exquisite: three

puffs of smoke and then peace and love" (Complete Letters

629). No wonder Wilde was popular with the flower children of the

sixties.

After prison, Ellmann writes: "Increasingly he [Wilde] sought assistance from stimulants, the favorite being the Dutch liqueur Advocaat, though he then switched to brandy and absinthe." Curiously, Ellmann adds: "They did not make him drunk, but they offered consolation" (562). This is a peculiar comment given the facts. When he was able to get up from his deathbed, Wilde "insisted on drinking absinthe," writes Ross to More Adey after Wilde's death, even though his doctor warned, "he could not live long unless he stopped drinking." Furthermore, Wilde "always drank too much champagne during the day" (Complete Letters 1212-1213). In another postmortem letter (to Adela Schuster), Ross writes of Wilde: "Like his brother he was inclined to take too much alcohol at times, but never regularly, and he never bore outward signs of it." In fact, says Ross, after Willie Wilde's death in 1899, Ross was able to get Wilde to quit for six months (Complete Letters 1225). Ordinarily, "normal" drinkers are not pressed to quit drinking like this. In the same letter, Ross writes of Wilde: "As long as he was allowed champagne, he had it throughout his illness" (1227, emphasis Ross's). Jean Dupoirier, the exceptionally kind and generous proprietor of Wilde's last abode, Hôtel d'Alsace, made sure Wilde had "four or five bottles a week of an excellent Courvoisier, at 25 and 28 francs" (Ellmann 577), and this was in addition to the drinking Wilde did outside his hotel. Add up all this evidence and it is strange no biographer has been willing to call Wilde alcoholic.

The evidence does not stop here. As Goodwin says,

"Alcoholism runs in families" (55), and besides Wilde's brother,

Willie, their father was also alcoholic, according to several

biographers. Hesketh Pearson, for example, says Sir William Wilde

was "addicted to alcohol" (11). Even Wilde's mother is said to

have over-indulged in liquor (Belford 280).3 That the

Irish had and have a high level of alcoholism is probably due more to

"family and cultural traditions . . . than to heredity" (Goodwin

98). The truth is, as Goodwin states, "the cause of alcoholism is

unknown"; still, there are "a number of 'risk factors,'" among them

"family history" (72). Moreover, Wilde fits the profile of an

adult child of an alcoholic as described by one of the foremost writers

in the field, Janet Geringer Woititz. Of her thirteen diagnostic

categories, Wilde to one degree or another fits every one, except

perhaps for Number 5: "Adult Children of Alcoholics have difficulty

having fun" (xxvi). Granted, Wilde was an extraordinary person, a

great writer and a raconteur of genius, as well as a person who

suffered a fate that was as degrading as it is legendary.

Nevertheless, he was as subject to the conditions that promote

addiction as anyone else.

Although one could write at great length about Wilde as an adult child of alcoholics (ACA), suffice it here to point out that he especially fits the following diagnostic categories:

7. Adult children of alcoholics have difficulty with intimate relationships.

8. Adult children of alcoholics over-react to changes over which they have no control.

9. Adult children of alcoholics constantly seek approval and affirmation.

10. Adult children of alcoholics usually feel that they are different from other people.

11. Adult children of alcoholics are super responsible or super irresponsible.

12. Adult children of alcoholics are extremely loyal, even in the face of evidence that the loyalty is undeserved.

13. Adult children of

alcoholics are impulsive. They tend to lock themselves into a course of

action without giving serious

consideration to alternative

behaviors or possible consequences. This impulsivity leads to

confusion, self-loathing and loss of

control over their environment.

In

addition, they spend an excessive amount of energy cleaning

up the mess. (Woititz xxvii)4

Briefly, let's look at the evidence to support

Wilde as an ACA, evidence any serious student of Wilde will recognize

instantly. Number 7: Wilde never formed a truly intimate

relationship for any considerable length of time, not even with his

wife, Constance. Number 8: There are many examples here. The

letters after he was in prison demonstrate his over-reaction to lack of

money. Had he not been so extravagant, he could easily have lived

within the means he was provided by his wife (see Ellmann 566 and Auden

320). Number 9: Wilde lived for social position and suffered

enormously when he lost it. Number 10: "I am far more of an

individualist than I ever was," he writes in De Profundis (Complete

Letters 731; all references to De Profundis are to this

edition); "I am one of those made for exceptions" (732).

To finish the list, Number 11: Wilde is

well-known for his extravagance

and hyper-generosity (irresponsible traits), yet he was "super

responsible" in his work as a lecturer in America and Great Britain, in

his work as an editor of Woman's World, and, for the most part,

in his work as an author. Number 12: Wilde's loyalty ("loyal to

the bitter extreme," as he writes in De Profundis 703) to

Bosie, who clearly did not deserve it, brought him ruin. And finally,

the unlucky--for Wilde at least--Number 13: except for the last part

about spending "an excessive amount of energy cleaning up the mess,"

unless one considers the whole of De Profundis such an effort,

Woititz might have been describing the débâcle of

1895: Wilde's suing of Queensbury, egged on my Bosie, his decision not

to flee to France, and his total "loss of control over . . . [ his]

environment" for two years in prison and the post-prison years in exile.

All of this helps explain the complexity of Wilde's

self-destructiveness. He came from a "dysfunctional" family (to

use an overused adjective): his father's drinking and sexual

irregularities are enough to support this (three illegitimate children

before marriage, alleged rape after marriage and a libel trial over the

accusation), and the problems of the children of such a family are

similar to those of an ACA. They include an over-concern with

appearances, hiding inner truth, "fear of intimacy," and "fear of

abandonment" (Hetherington 44-49). Though I am focusing on Wilde's

addictions (which naturally include his addictive personality, stemming

in part from his upbringing), I do not claim my approach is the

complete explanation: that no doubt will never be known. Alcoholics by

definition are self-destructive, and an adult child of alcoholics (or

an alcoholic if you exclude Wilde's mother) is laden with an extra

layer, as it were, of self-destructive traits.

Very few people, even members of Alcoholics

Anonymous, know the role C. G. Jung played in its founding. An

overview of Jung's role will shed light on Wilde's addictions, for what

Jung said about alcohol applies equally to any addiction, even those

never dreamed of when Jung was alive. A friend, Edwin T., of the

future co-founder of AA, Bill Wilson, had gotten sober with the help of

one Roland H., an alcoholic who had worked to get sober without success

with Jung for about a year. Jung told Roland H. frankly that his

case was hopeless unless, in Wilson's paraphrase, "he could become the

subject of a spiritual or religious experience--in short, a genuine

conversion," which subsequently happened (Letter to Jung from Bill

Wilson, 23 January 1961, "The Bill W.--Carl Jung Letters" 27).

Bill Wilson wrote to Jung in January 1961, some thirty years after the

event, to thank him for starting the "chain of events" that led to the

founding of AA (29). In his reply, dated 30 January 1961, Jung

writes that thirty years before he had to be very cautious about

anything he said regarding spiritual matters because he "was

misunderstood in every possible way" (Jung, Selected Letters 197).

Given Wilson's "decent and honest letter," which shows his

understanding of alcoholism, Jung feels he can be more open with him.

Roland H.'s "craving for alcohol," Jung writes, "was the equivalent on

a low level of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness,

expressed in medieval language: the union with God." "You see," Jung

concludes in language Wilde would certainly have understood, if not

accepted, "alcohol in Latin is spiritus and you use the same

word for the highest religious experience as well as for the most

depraving poison. The helpful formula therefore is: spiritus contra

spiritum" (Selected Letters 198). Wilde's

well-documented flirtation with Catholicism, his quixotic exaltations

of Christ in "The Soul of Man under Socialism" and in De Profundis,

and his supposed deathbed conversion to Catholicism,--all these and

more are manifestations of the deep spiritual need in Wilde he was

trying to fill with alcohol and other drugs (opium, hashish, and

cigarettes) and his romance addiction. As a man whose primary

sexual/romantic desires were directed towards other men, particularly

younger men, he was an outsider in a society which condemned him and,

partly because of his romance addiction, imprisoned him because of his

efforts to fill that spiritual need.

In "The Soul of Man under Socialism," Wilde writes: "the message of Christ to man was simply 'Be thyself.' That is the secret of Christ" (263). Unfortunately, Wilde was to learn that he could not live up to Christ's message, as Wilde saw it: "try to shape your life that external things will not harm you" (264). Stripped of "external things" and having reached what recovering alcoholics and addicts call a "bottom" in prison, Wilde writes again about Christ in his long epistle to Bosie, his homme fatale. Wilde recalls what he had written about Christ in "The Soul of Man": "that he who would lead a Christ-like life must be entirely and absolutely himself" (Complete Letters 740). He then proceeds to describe an unorthodox Christ of his own making: "the supreme Individualist . . . the first in History" (744). Yet, as if he were anticipating the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous, whose first step begins, "We admitted we were powerless over alcohol" (Alcoholics Anonymous {the so-called Big Book of AA} 59), Wilde proclaims Christ's "submission, his acceptance of everything" (742). He describes how, having lost everything he once held dear, including his "own eldest son," he "saw . . . that the only thing for me was to accept everything" (744). In prison, away from the "fixes" of his alcoholic and romantic addictions, he had spiritually grown to a point where he might have begun recovery. He might have found a way to fill the "vacuum of affirmative selfhood" (Doylen 553). The evidence of De Profundis, however, and the letters after it, shows that Wilde's new-found wisdom was indeed temporary.

That Wilde was homosexual is not irrelevant. Though there are no studies of which I'm aware about the incidence of alcoholism and other addictions among homosexuals during Wilde's lifetime, recent research "consistently shows a higher incidence of alcoholism and/or other forms of chemical dependency in gay and/or lesbian persons" (Kus 2). Furthermore, as Sheppard B. Kominars states, "One of the greatest obstacles to long-term sobriety for gay men and lesbians is internalized homophobia. The fear of, and hatred of, one's homosexuality is a major cause of relapse in the recovery process of the chemically dependent gay man, lesbian, and bisexual" (29-30). Kominars also states: "Acknowledging ourselves as we are, and allowing others the same freedom provided the baseline for change" (32, emphasis Kominars's). Had Wilde been able to follow Christ's example, as Wilde himself conceived it--"so he who would lead a Christ-like life is he who is perfectly and absolutely himself" ("The Soul of Man" 266)--he would have had a chance to overcome his addictions.

Auden, a keen student of both Freud and Jung, recognizes the acute insecurities of both Wilde and Bosie (Lord Alfred Douglas). Auden bases his conclusions on Wilde's being "overloved and indulged by his mother" (312) and Bosie's being "hated and rejected by his father" (310-311). I don't disagree. However, the profound feelings of unworthiness shared by both Wilde and Bosie are also characteristic of addicts (Carnes 108-109).

I have neither the time nor the space to analyze the character of Bosie Douglas here. However, since he figures so prominently in Wilde's romance addiction, a few words are in order. His life-long nickname stems from his mother's calling him "by the West Country diminutive 'Boysie,' meaning simply 'little boy,' which gradually shortened to 'Bosie' [. . . and] he remained at heart a little boy until his death" (Murray 12). The same may be said for Wilde. Apart from the betting, both shared addictions to "Boys, brandy, and betting," as Wilde famously says of Bosie in a letter to Ross written at the end of June 1900 (Complete Letters 1192). They were both what Jung called pueri aeterni, eternal youths. Like Wilde, Bosie's statements are not to be taken literally. But whereas Wilde based an aesthetic theory on "The Decay of Lying" and "The Truth of Masks," Bosie was a pathological liar, which any careful reader of De Profundis will discover.5 He gives himself undue credit for Wilde's writing during their relationship when Wilde himself, with some exaggeration, writes in what Ross would publish as De Profundis: "I remind you [Bosie] that during the whole time we were together I never wrote one line" (Complete Letters 683; see Douglas, Foreword xi). One of Bosie's biggest lies is that he became heterosexual after marriage to a woman and conversion to Catholicism. Even an otherwise astute queer critic such as Gary Schmidgall writes: "Boys apparently ceased to monopolize Bosie's attention" after his marriage and conversion (445 n.). Samuel M. Steward's Chapters from an Autobiography provides ample proof of Bosie's duplicity on the question of his life-long queerness. Steward was a professor, a prolific writer, and close friend of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. He writes in his memoirs that in his twenties he visited the 67-year-old Bosie in England with the idea of going to bed with him in order to be "linked" with Wilde (51). Even while disclaiming "homosexual leanings and entanglements . . . [since] he became a Catholic" (50), after enough booze, Bosie and Steward were "in bed" and Steward's "lips [were] where Oscar's had been" (51). Given Steward's description of Bosie, matched by Bosie's biographers', right down to the prominent nose (see Hyde, Lord Alfred Douglas 300), the story is credible.

Wilde and Bosie, Oxford, c. 1893

Steward contends that after their sex and while still in bed, Bosie said: "You really needn't have gone to all that trouble, since this [meaning mutual masturbation] is almost all Oscar and I ever did with each other" (51). Even here Bosie would appear to be disingenuous, for H. Montgomery Hyde, biographer of Wilde and Bosie, quotes Bosie's letter to Frank Harris in which Bosie admits to practicing with Wilde "a species of oral homosexual intercourse" (Hyde, "Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas" 146; Hyde's words). In his biography of Bosie, Hyde quotes Bosie's letter more fully; to wit: "he [Wilde] 'sucked' me" (28). Bosie further lied to Steward by claiming he and Wilde got "boys for each other . . . . I could always get the workers he liked, and he could get the intellectual ones I preferred" (51). Bosie's latest biographer dispels this lie about the type of boys Bosie preferred: "The sexual relationship between Wilde and Douglas was short-lived , but it was replaced in both by a taste for rent-boys" (Murray 43).

Nevertheless, what evidence exists seems to

suggest Wilde did indeed prefer oral to anal sex. During Wilde's

second trial, the "rent-boy" Charles Parker testified that Wilde

"committed the act of sodomy upon me" (Hyde, Trials 171).

However, he also testified he had "to do what is vulgarly called

'tossing him off' . . . 'and he would often do the same to me,'" yet

Parker would never "permit him to insert 'it' in my mouth . . ."

(172). This evidence, plus the fact that "by the mid-nineteenth

century [sodomy] is identified principally as sex between men," a very

vague definition to say the least (Cohen 5; see also 84: before 1885,

"felonious buggery" was more likely to refer to anal intercourse),

suggests that Wilde's favorite sexual practices with young men, at

least before his trials, did not include anal sex.6

Now I will discuss Wilde's romance addiction.

The topic of romance was, of course, a favorite in Wilde's pre-prison

work. In The Importance of Being Earnest, for instance,

Jack tells Algernon he has "come up to town expressly to propose to"

Gwendolen. Algernon replies: "I thought you had come up for pleasure? .

. . I call that business.

JACK: How utterly unromantic you

are!

ALGERNON: I really don't see

anything romantic in proposing. It is very romantic to be in love.

But

there is nothing romantic about a definite proposal. Why,

one may be accepted. One usually is,

I believe. Then the excitement is

all over. The very essence of romance is

uncertainty. (Plays 350)

Algernon speaks like a true romance addict. In An Ideal Husband,

Lord Goring remarks: "To love oneself is the beginning of a life-long

romance . . . . (Plays 292). As an addict, Wilde never truly

learned to love his inmost self, a necessary task before one can truly

love another.

The main texts I will use to examine Wilde's romance addiction are his letters, particularly his long letter written in Reading Goal to Lord Alfred Douglas which Robbie Ross called De Profundis, but which Wilde himself called Epistola: In Carcere et Vinculis, implying that he knew one day it might be published, even though it is addressed specifically to Bosie (Complete Letters 782; for a brief history of the letter, which runs from page 683 to 780 in The Complete Letters, see Complete Letters 683 n. 1). Leaving aside his notion of Wilde's "transgressive aesthetic," I agree with Jonathan Dollimore that De Profundis "registers . . . Wilde's courage and his despair during imprisonment . . . [and] also shows how he responded to the unendurable by investing suffering with meaning" (95). Part of the dynamic in Wilde's relationship with Bosie, as Schmidgall puts it, is that Wilde "sought to retain his youth vicariously, by association" (194). Now, in prison, Wilde, rather like Lord Henry to Dorian Gray, plays the role of the archetypal wise old man, the senex, to Bosie's puer aeternus (see Snider 77-79; the puer aeternus is the eternal youth archetype; see also Jung, Symbols 258-259), except that Wilde, having suffered more than Lord Henry could ever dream of in his worst nightmares, speaks authoritatively, if not always accurately, with the heavy weight of experience. Sadly, and ironically, Wilde himself is a puer aeternus too, as we shall see.

Wayne Koestenbaum, in a perspicacious

reader-response essay, argues that "Wilde posits an essential 'gay

identity' [in De Profundis and "The Ballad of Reading Goal"] in

order to develop gay writing and gay reading as reverse discourses"

(236). If De Profundis teaches gay readers anything, as

Koestenbaum contends, it teaches mostly by negative example, given the

context of Wilde's complete oeuvre. As I have suggested, the

wisdom Wilde gains through suffering evaporates within months of his

release from prison. Literally like an alcoholic relapsing, he

moves from senex to puer, albeit never losing the wit

and erudition he was famous for. What he lost, in Jungian

parlance, was his exalted persona, the mask (to use Wilde's word) he

wore before the world, and this was too much to bear.

De Profundis confirms the fact that Wilde

was a romance addict. In a perceptive study of "Sexual Compulsivity in

Gay Men," Jungian analyst John A. Gosling writes that

sexual compulsivity in some persons may be understood as a powerful urge to connect with "something" that is compelling and fascinating, over which the individual feels he has little or no control. In this context, the basic instinct is sexual in nature and for gay men the compelling object is the phallus. Being in the presence of the phallus can be a "numinous" experiencne (resulting in a connection with transpersonal or spiritual energies . . .) although the person may not be aware of it. (149)

For Wilde, however, the phallus, the erect penis (see Monick 9 and 16), is not the inspiration, the primary numinous subject of his homoerotic fantasies. Rather, the face and the body of the beautiful young man inspire him; these are what he romanticizes. Instead of Priapus, his ideal is Antinous. For the queer sex addict as described by Gosling, Priapus, "the Roman god whose enormous erection will not go away" (Monick 106) is the operative archetype. For the queer romance addict, Antinous, the supremely handsome young lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian, is the shining ideal (see Complete Letters 1022).

To Antinous, in Wilde's personal myth, we need to add Hyacinthus, the gorgeous boy loved by Apollo, and Marsyas, the Phrygian flute player, symbol of the suffering, sacrificed artist, who challenged Apollo and lost and whose punishment was to be skinned alive. As if anticipating his own fate, in "The Decay of Lying" Wilde praises Marsyas, "not Apollo," as "the singer of life" (Intentions 314); and, alone in his prison cell, he remembers Marsyas: "I hear in much modern Art the cry of Marsyas. It is bitter in Baudelaire, sweet and plaintive in Lamartine, mystic in Verlaine" (Complete Letters 756). Until his prison writings, Wilde is far more Romantic, with a capital R, than a realist. But it is his romance addiction (with a small r), I wish to examine. For this I add one more classical archetype, Dionysus, Greek god of wine and frenzy, of uninhibited sensual abandon, to the constellation of archetypal figures which govern Wilde's alcohol and romance addictions.

In her ground-breaking book, Escape from Intimacy, Anne Wilson Schaef classifies romance addiction as one of the "process addictions," which are "much more subtle and tricky than substance addictions" (2), such as alcoholism and other drug addictions. Furthermore, "most of the books in the field combine and thus confuse" sex, romance, and relationship addictions. In fact, they are "three separate addictions" (3). It's easy to understand why the three are often combined: they often go together in obvious ways. The sex addict may create romantic situations or illusions to get the sex he wants (for convenience, and since I am referring primarily to a gay man, I will use the the masculine pronoun, though of course there are sex, romance, and relationship addicts of all genders and sexualities). The romance addict may enter into relationships even though he cares little about sex or the intimacy a deep relationship calls for. Sex would again be involved. And one can be addicted to more than one of these process addictions (others include addictions to "work, money . . . religion, [and] exercise," Schaef 2). It seems superfluous, but probably necessary, to add "that addictions are not matters of morality; they are progressive, fatal diseases" (Schaef 5). Finally, Schaef reminds us "addictive relationships are the norm for our culture" (7). If this is true for our culture, it was no less true for the Victorians with their mania for collecting, for rectitude, and for sentimentality, not to mention all the other addictions Schaef cites.

After examining Wilde's life and letters

carefully, I have come to the conclusion that he is not a sex addict,

although he might seem so. His famous simile in De Profundis

to describe his relationships with the rent-boys, "It was like feasting

with panthers" (Complete Letters 758), seems to suggest a

roaring sex life. He even uses a rare phallic image: "They were

to me the brightest of gilded snakes" (759). But the language is

so striking, so poetic, it brings the element of romance to the

description:

The danger was half the

excitement. I used to feel as the snake-charmer must feel when he lures

the cobra to stir from the painted cloth or reed-basket that

holds it, and makes it spread

its hood at his bidding, and sway to and fro in the air as a

plant sways

restfully in a stream . . . . Their poison was

part of their perfection. (758-759)

With his alliterative prose, Wilde goes on, as he does over and over in his long, lecture-like epistle, to fling blame at Bosie and his father: "I did not know that when they were to strike at me it was to be at your piping and for your father's pay" (759). In another place, Wilde writes: "Desire, at the end, was a malady, or a madness, or both . . . . I ceased to be Lord over myself. I was no longer the Captain of my Soul" (730). If Wilde's description seems like sex addiction, it should be accompanied by the testimony of the boys, the charmers and the charmed. Charles Parker, for example, describes a dinner with Wilde: "The table was lighted with red-shaded candles. We had plenty of champagne with our dinner and brandy and coffee afterwards" (Hyde, Trials 171). Then there were the expensive gifts, the silver cigarette cases (189). These are hardly compulsive encounters in a public lavatory. They are romantic encounters, staged by a master dramatist.

As Schaef says, "The romance addict is in love with the idea of romance. The romance addict does not really care about the other person." He is "an expert in illusion, in fact, lives in illusion" (47, emphasis Schaef's). The "fix" comes "from 'love' and romance, not from sex, not from relationships" (46). And of course Wilde's central romance, one just as fatal as the mini-romances with the rent-boys, was that with Bosie. In the letter that was used in a failed effort to blackmail Wilde and as evidence against him in court, Wilde plays the roles of both senex and romantic lover. "My Own Boy," Wilde writes to Bosie in January 1893,

Your sonnet is quite lovely, and it is a marvel that those red rose-leaf lips of yours should have been made no less for music of song than for madness of kisses. Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry. I know Hyacinthus, whom Apollo loved so madly, was you in Greek days . . . . (Complete Letters 544)

After another paragraph about more mundane things, Wilde ends with, "Always, with undying love, yours [,] Oscar" (544). This is the language of high romance, of infatuation, and, yes, of love. But the love is not more important than the romance. Bosie's renowned good looks, his aristocratic title, his aspirations as a poet, his being at Wilde's own college at Oxford, and not least his impulsive personality, including a love of the accoutrements of high living,--all these explain why Wilde preferred Bosie to Robbie Ross or John Gray. As Ellmann puts it: "In temperament he [Bosie] was totally spoiled, reckless, insolent, and, when thwarted, fiercely vindictive. Wilde could see only his beauty . . ." (324).

But why did Wilde continually take Bosie back after all kinds of scenes, lies, extravagant outlays of Wilde's money, and interruptions of Wilde's creative time? Why did he not end their "fatal friendship" (693 and 770)? Repeatedly, Wilde accuses Bosie of a "lack of imagination," his "one really fatal defect of . . . character" (709) and berates him for having "the supreme vice, shallowness" (715). Had Wilde refused to see Bosie after his release from prison, one might believe all this vituperation. However, just as he had accepted Bosie back approximately every three months, as he says in De Profundis, so he returned to live with him in Naples after his release and with the certainty of losing his income from his wife for doing so. Clearly we are dealing with an addiction here, but not a sexual addiction (for Wilde and Bosie sex was never an important part of their relationship), and not a relationship addiction, for both sought other sexual partners and never took the time really to become intimate with each other. The addiction was romance, and for Wilde it was as fatal as any drug.

Within five months after his release from prison (September 1897), Wilde was living with Bosie in Naples. In defense of his decision, he writes to Turner:

Much that you say in your letter is right, but still you leave out of consideration the great love I have for Bosie. I love him, and have always loved him. He ruined my life, and for that reason I seem forced to love him more: and I think that now I shall do lovely work . . . whatever my life may have been ethically, it has always been romantic, and Bosie is my romance. My romance is a tragedy of course, but it is none the less a romance, and he loves me very dearly, more than he loves or can love anyone else, and without him my life was dreary. (948, emphasis Wilde's)

Wilde adds: "So stick up for us, Reggie, and be nice." We know

in retrospect that Wilde did not do "lovely work" living with Bosie.

Apart from finishing "The Ballad of Reading Goal" in Naples, he added

nothing to his creative oeuvre. The key words in this letter are

"seem forced" and "without him my life was dreary": the romance addict

without his fix is compelled to find it again. Others intervened

to break them apart, but doubtless they would have broken up in time,

for the old pattern had reasserted itself. Bosie was again spending

Wilde's meager funds as if he were entitled to them (Ellmann

555). It was the same fatal process Wilde had wailed about in De

Profundis. Disease is no respecter of people, time, or place.

Schaef describes four levels of romance

addiction. The first two fit Wilde well. The first level

"is the person who practices his or her addiction almost completely in

fantasy," and in the second level "romance addicts act out their

fantasies" (62). Third level addicts act out "in such a way that

it is harmful to themselves and others and may even verge upon

or be illegal" (64, emphasis Schaef's). This level also applies

to Wilde given the fact that were it not for him Alfred Taylor, the

person through whom Wilde met his rent-boys, would not have been tried

and convicted, never mind the harm Wilde did himself through his

romantic addiction to Bosie. As for the illegal actions, the

applicable laws no longer apply (and of course never should have been

on the books).7

As far as Schaef's first level goes, Wilde's

fantasy life was rich when it came to attractive young men.8

Young male fans of his wrote to him, and soon Wilde, after asking for a

photograph, would be flirting with them, even though they had never

met. One of these fantasy romances was with H. C. ("Jerome," as

he preferred) Pollitt. Wilde writes to him on 3 December 1898: "Mrs

Leverson, a recognised authority for the colour of young men's hair,

assured me you were quite golden, and I have always thought of you as a

sort of gilt sunbeam masquerading in clothes . . . . (Complete

Letters 1106-07).

Another such unmet young man, Louis Wilkinson,

was a student at Radley who made up a story about a dramatic society

that wanted to make a play of Dorian Gray so that he could

strike up a correspondence with Wilde. In this Wilkinson

succeeded, no doubt beyond his wildest ambitions. Before long

Wilde was flirting with him via the postal system. In a letter

postmarked 3 February 1899, Wilde describes a photo Wilkinson had sent

him: in it "you have the eyes of the poet, and your hair is charming. I

am sure it is shot with wonderful lights, and I like the curve of its

curl" (1122). Wilde goes on to comment favorably (of course) on a poem

Wilkinson had sent him and to express the "hope" he would "devote

himself, with vows, to poetry. It is a sacramental thing, and there is

no pain like it" (1122). Perhaps here Wilde has Marsyas in

mind. Before long, Wilde is addressing Wilkinson in language

usually reserved for Bosie or Maurice Gilbert, an Antinous who became a

close friend: "My dear Boy" (1133). As with Bosie and Maurice,

the salutation illustrates Wilde's dual roles (at least in his

fantasies) of lover and senex.

Holland and Hart-Davis describe Maurice Gilbert

as "one of Wilde's closest and most devoted friends during these last

years [1898-1900]. Except that his father was English and his mother

French, and that he was a young soldier in the marine infantry, nothing

is known of him" (1025 n. 4). If one reads the letters, however,

this note is one of the very few instances in which Holland and

Hart-Davis are simply wrong. The letters reveal much. In addition

to being loved by Wilde, Gilbert was Bosie's lover and also beloved by

Ross and Turner. As Belford puts it: "As lover to the whole

group, Gilbert linked them together and symbolized how homosexual love

could germinate without jealousy" (296). The letters do support Belford

here, though how much sex was involved, if any, between Wilde and

Gilbert, is hard to say. What is clear is Wilde's romantic

attachment to Gilbert. Punning on his own name, Wilde writes to Turner

on 11 May 1898: "How is my golden Maurice? I suppose he is wildly

loved. His upper lip is more like a rose-leaf than any rose-leaf

I ever saw" (1066). Since he uses the same diction he had used to

praise Bosie, it would seem Gilbert has taken Bosie's place as the

romantic image in his fantasies. Later in the same month of May

and also to Turner, Wilde refers to "our dear Maurice. He appeared,

jonquil-like in aspect, a sweet narcissus from an English meadow"

(1074). And to Ross a few days later Wilde writes of Gilbert: "He

is a great dear, and loves us all, a born Catholic in romance; he is

always talking of you and Reggie" (1076). Gilbert was at Wilde's

deathbed (Complete Letters 1219) and at Ross's request took the

photograph of Wilde lying in state.

Then there are the hustlers. Writing to Ross in February 1898, Wilde enunciates his oft-quoted defense of homosexuality: "A patriot put in prison for loving his country loves his country, and a poet in prison for loving boys loves boys. To have altered my life would have been to have admitted that Uranian love is ignoble. I hold it to be noble--more noble than other forms" (1019). He had paid what would turn out to be a fatal price for his "loving boys" in England (an ear injury in prison was the seed of his final illness, meningitis), and in addition to the fantasy romances I have described, he would act out his fantasies with young men in France and in Italy (Scheaf's second level of romance addiction).

Jean Matet, Wilde: cabaret, rue de Dunkerque

Wilde's letters to his gay friends often contain

gossip about the various young men Wilde has met. Whether they

were sexual partners or not, Wilde describes them typically in romantic

terms. He wonders whether Turner remembers "the young Corsican at

the Restaurant Jouffroy? His position was menial, but eyes like

the night and a scarlet flower of a mouth made one forget that: I am

great friends with him. His name is Giorgio: he is a most

passionate faun" (letter postmarked 26 November 1898, 1104).

One of the reasons Wilde was so unhappy staying in Gland, Switzerland, as the guest of the wealthy and gay Harold Mellor, apart from what he considered Mellor's stinginess, was the "lack of physical beauty" in the Swiss (1132). He complained about it over and over. A letter to More Adey in March 1899 proves Wilde had not lost his wit: "At Nice I knew three lads like bronzes, quite perfect in form. English lads are chryselephantine. Swiss people are carved out of wood with a rough knife, most of them; the others are carved out of turnips" (1129). He also complained about Mellor's closetedness: he "has Greek loves, and is rather ashamed of them" (1132). If Wilde is a gay martyr, he is also an exemplar of the uncloseted gay man who refuses to bend to the world's homophobia--a position which, for him, came at a great price.

If Switzerland was barren ground for the romance

addict, Italy was a veritable garden. Here is Wilde writing to Ross

from Rome in April 1900:

I have given up Armando, a very smart elegant young Roman Sporus. He was beautiful, but his requests for raiment and neckties were incessant: he really bayed for boots, as a dog moonwards. I now like Arnaldo: he was Armando's greatest friend, but the friendship is over. Armando is un invidioso apparently . . . . (1182; the Italian is glossed as "Jealous" n. 3)

How much of this is literally true and how much fantasy we can not know.

Despite the obvious delight with which Wilde describes his "tricks," to use a modern word, he felt equivocal about them. He says in a letter to Ross from Rome (14 May 1900):

In the moral sphere I have fallen in and out of love, and fluttered hawks and doves alike. How evil it is to buy Love, and how evil to sell it! And yet what purple hours one can snatch from that grey slowly-moving thing we call Time! My mouth is twisted with kissing, and I feed on fevers. The Cloister or the Café--there is my future. I tried the Hearth, but it was a failure. (1187)

Like an addict trying to quit his "drug of

choice," Wilde shows his frustration with having "to buy Love."

In his last extant letter to Louis Wilkinson, someone who, because of his education (he was going to Oxford) and writing talents, might have been another Bosie or Maurice Gilbert, Wilde writes in July 1900 from the Hôtel d'Alsace in Paris:

Dear Boy, Come and see me next week. I can get you a room in my hotel. I am not going to write to you any more: I want to see you. I have waited long enough. (1192)

The progression of his romance addiction is fairly clear here. The long-distance romance he had with Wilkinson no longer fills that spiritual vacuum which plagues him. He needs more; he needs the physical presence of the fantasy object. Wilkinson never came, but he did send a wreath of flowers to Wilde's funeral (1222).

Schaef writes that "romance addiction keeps

individuals . . . immature" (72). And some fifty years ago one

of Wilde's biographers noted Wilde's "emotional life . . . never

reached maturity" (Pearson 285). Worse than that, his addictions,

whatever their causes (and homosexuality was not one of them),

led him on a path of inevitable self-destruction. His final

illness can not have been helped by his drinking and smoking cigarettes

nearly to the end. Nevertheless, during his last years perhaps

the drinking and the romancing ironically alleviated some of the pain

caused by those very addictions and by his loneliness and the routine

rejections of those who used to honor him. Wilde's work remains.

By now it has passed the "test of time." As a gay icon he remains

both a positive and a negative example to all sexual minorities just as

he remains one of the best as well as one of the most popular writers

from the late nineteenth-century.

1My purpose here is not to debate

the recent critical discussions about the so-called "construction" of

homosexuality and the appropriateness of using the terms "gay,"

"queer," and "homosexual" applied to Wilde and other

pre-twentieth-century figures. There is some truth on all sides, but my

feeling is that, as far as his sexual orientation goes, Wilde can not

be called anything other than homosexual (or gay or queer) in the

modern usage of the word, particularly as he is seen as such by twenty-

and twenty-first century critics and the public. For a detailed

discussion of some of these issues, see Joseph Bristow's "'A complex

multiform creature': Wilde's Sexual Identities" in The Cambridge

Companion to Oscar Wilde.

2I started my research with the

hypothesis that Wilde was also a sex addict, but although there is some

evidence for this, it is too slim to support such a thesis. Also, I

know some experts in alcoholism refute the idea it is a disease.

Nevertheless, I agree with one of the foremost experts on the subject,

Donald W. Goodwin, who writes: "I am convinced that alcoholism is an

illness and not a vice. I do not believe victims of alcoholism got that

way because they exercised free will and chose to get that way" (ix).

3For this Belford provides evidence from another of Wilde's biographers, Richard Sherard, who "observed Willie drunk," when Wilde stayed "at Oakley Street between his trials . . . and Lady Wilde" went to her bed "with a bottle of gin" (Belford 280). This one incident, of course, hardly proves Wilde's mother was alcoholic, particularly given the fact that, as Holland states, Sherard "wrote vividly if with questionable accuracy about . . . [his] friendship with Wilde" ("Biography" 5). See also Frances Winwar's Oscar Wilde and the Yellow 'Nineties (9).

4The categories I omit yet which still apply to Wilde to some extent are the following: "1. Adult children of alcoholics guess at what normal behavior is." They "have difficulty following a project through from beginning to end" (Number 2); they "lie when it would be just as easy to tell the truth" (Number 3); they "judge themselves without mercy" (Number 4); and they "take themselves very seriously" (Number 6; Woititz xxvi).

5For example, Wilde recounts his experience of having caught the flu from Bosie after having nursed him during his illness. Bosie not only refuses to nurse Wilde; he also lies about his behavior (Complete Letters 697).

6According to William Stewart,

"sodomy has served historically as an umbrella term for any sexual

practice to which sexual moralists took offense" (239). Wilde was

"charged . . . with committing acts of gross indecency with various

male persons" (Hyde, Trials 154).

7I know of no evidence that Wilde

experienced the fourth level, "violent romantic behavior" (Schaef 65).

8That the boys had to be attractive

is illustrated by the well-known, and unfortunate, incident during

Wilde's first trial, against Queensbury. Wilde was asked if he had

kissed Walter Grainger, a lad of about sixteen. As Hyde reports, Wilde

replied, "in a fatal moment of folly": "'Oh dear no!' . . . 'He was a

peculiarly plain boy. He was, unfortunately, extremely ugly. I pitied

him for it'" (Trials 133).

Works Cited

Alcoholics Anonymous. Alcoholics Anonymous. 4th ed. New

York:

Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, 2001.

Auden, W. H. "An Improbable Life." Rev. of The Letters of Oscar

Wilde. The New Yorker 9 March 1963.

Rpt. in Forewords and Afterwords. By W. H.

Auden. New York: Vintage, 1974. 302-324.

Belford, Barbara. Oscar Wilde: A Certain Genius. New York: Random, 2000.

Bennett, Arnold. "Arnold Bennett on Wilde as an Outmoded Writer."

1927. Oscar Wilde:

The Critical Heritage. Ed. Karl Beckson.

New York: Barnes &

Noble,1970. 417-418.

Bristow, Joseph. "'A complex multiform creature': Wilde's Sexual

Identities." The Cambridge

Companion to Oscar Wilde. Ed. Peter Raby.

Cambridge:

Cambridge UP, 1997. 195-218.

Carnes, Patrick. Out of the Shadows: Understanding Sexual

Addiction. 3rd ed. Center City, Minnesota:

Hazelden, 2001.

Dollimore, Jonathan. Sexual Dissidence: Augustine to Wilde,

Freud to Foucault. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991.

Douglas, Lord Alfred. Foreword. Oscar Wilde and the Yellow

'Nineties. By Frances Winwar.

Garden City, NY: Blue Ribbon, 1940.

Doylen, Michael R. "Oscar Wilde's De Profundis: Homosexual

Self- fashioning on

the Other Side of Scandal." Victorian

Literature and Culture 27 (1999):

547-566.

Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde. New York: Knopf, 1987.

Goodwin, Donald W. Alcoholism: The Facts. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000.

Gosling, John A. "Sexual Compulsivity in Gay Men from a Jungian

Perspective." Addictions in the

Gay and Lesbian Community. Eds. Jeffrey R. Guss

and Jack Drescher. New York: Haworth, 2000. 141- 167.

Hetherington, Cheryl. "Dysfunctional Relationship Patterns: Positive

Changes for Gay

and Lesbian People." Addiction and Recovery in

Gay and Lesbian Persons.

Ed. Robert J. Kus. New York: Haworth, 1995. 41-55.

Holland, Merlin. "Biography and the Art of Lying." The Cambridge

Companion to Oscar Wilde.

Ed. Peter Raby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. 3-17.

---. The Wilde Album. New York: Holt, 1997.

--- and Rupert Hart-Davis, eds. The Complete Letters of

Oscar Wilde. By Oscar Wilde. New York: Holt, 2000.

Hyde, H. Montgomery. Lord Alfred Douglas: A Biography.

New York: Dodd, Mead, 1984.

Jung, C. G. Selected Letters of C. C. Jung, 1909-1961. Ed.

Gerhard Adler. Princeton: Princeton UP,

1984.

---. Symbols of Transformation: An Analysis

of the Prelude to a Case of Schizophrenia . 2nd. ed.

Trans. R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1967.

Vol. 5 of The Collected Works of C. G. Jung.

Koestenbaum, Wayne. "Wilde's Hard Labor and the Birth of Gay

Reading." Oscar Wilde:

A Collection of Critical Essays. Ed. Jonathan

Freedman. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice, 1996.

234-247.

Kominars, Sheppard B. "Homophobia: The Heart of the Darkness." Addiction

and Recovery in

Gay and Lesbian Persons. Ed. Robert J. Kus. New

York: Haworth, 1995. 29-39.

Kus, Robert J., ed. Addiction and Recovery in Gay and

Lesbian Persons. New York: Haworth, 1995.

Lahr, John. Introduction. The Plays of Oscar Wilde. By

Oscar Wilde. New York: Vintage, 1988.

Monick, Eugene. Phallos: Sacred Image of the Masculine. Toronto: Inner City, 1987.

Murray, Douglas. Bosie: A Biography of Lord Alfred Douglas. New York: Hyperion, 2000.

Pearson, Hesketh. The Life of Oscar Wilde. London: Methuen, 1954.

Schaef, Anne Wilson. Escape from Intimacy, the

Pseudo-Relationship Addictions:

Untangling the "Love" Addictions: Sex, Romance,

Relationships. New York: Harper, 1989.

Schmidgall, Gary. The Stranger Wilde: Interpreting Oscar. New York: Dutton, 1994.

Snider, Clifton. The Stuff That Dreams Are Made On: A Jungian

Interpretation of Literature.

Wilmette, Illinois: Chiron, 1991.

Steward, Samuel M. Chapters from an Autobiography. San Francisco: Grey Fox, 1981.

Stewart, William. Cassell's Queer Companion: A Dictionary of

Lesbian and Gay Life and Culture.

London: Cassell, 1995.

Wilde, Oscar. The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde. Ed.

Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis.

New York: Holt, 2000.

---. "Impressions of America." 1883. The Artist as Critic:

Critical Writings of Oscar Wilde.

Ed. Richard Ellmann. Chicago: U of Chicago P,

1969. 6-12.

---. Intentions. 1891. The Artist as Critic: Critical

Writings of Oscar Wilde.

Ed. Richard Ellmann. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1969.

290-432.

---. The Plays of Oscar Wilde. New York: Vintage, 1988.

---. "The Soul of Man under Socialism." 1891. The Artist as

Critic: Critical Writings of Oscar Wilde.

Ed. Richard Ellmann.

Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1969.

255-289.

W[ilson], Bill and C. G. Jung. "The Bill W.--Carl Jung Letters." AA

Grapevine Nov. 1978: 26-31.

Winwar, Frances. Oscar Wilde and the Yellow 'Nineties. Garden City, NY: Blue Ribbon, 1940.

Woititz, Janet Geringer. Adult Children of Alcoholics. Expanded

ed. Deerfield Beach, Florida:

Health Communications, 1983.

--Copyright © Clifton Snider 2009

This essay originally appeared, in shorter form, in The Wildean: A Journal of Oscar Wilde Studies 23 (2003), published by the Oscar Wilde Society <www.oscarwildesociety.co.uk>.