Fig. 1, Ecce Ancilla Domini, 1850, by

D. G. Rossetti,

whose sister, Christina, was the model for the

virgin.

"There is No Friend like a Sister":

Psychic Integration in Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market

I

Fig. 1, Ecce Ancilla Domini, 1850, by

D. G. Rossetti,

whose sister, Christina, was the model for the

virgin.

"There is No Friend like a Sister":

Psychic Integration in Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market

I

Within the last twenty-five years or so, Christina Rossetti has benefited from renewed scholarly examination, not in small part due to feminist interest in her work as an important woman poet in the nineteenth century.1 Her Goblin Market and other Poems (1862) was the first popularly successful book of Pre-Raphaelite poetry (Swann 92), and the title poem is generally considered Rossetti's masterpiece. In February 1964, for instance, Peter Quennell, writing to The New York Times Book Review, stated his belief that Goblin Market "establishes her claim to immorality" (qtd. by Bellas 37). A nineteenth-century fairy tale, Goblin Market is Rossetti's longest and most discussed poem, as well as her most popular poem, one that can be enjoyed by both children and adults.2

Goblin Market has been interpreted in many different ways. Although, as Katherine Mayberry points out, "the New Critical approach was never applied to" Rossetti's work as a whole (2), numerous other approaches have been applied. Until recently, the most frequent approach to her work in general and to Goblin Market in particular has been the biographical approach, with an emphasis on her supposed love life and her deeply held religious beliefs (she was an Anglo-Catholic). Referring to Goblin Market, her brother and posthumous editor, William Michael Rossetti, in an oft-quoted statement, declared: "I have more than once heard Christina say that she did not mean anything profound by this fairy tale--it is not a moral apologue consistently carried out in detail." He adds, however: "Still, the incidents are such as to be at any rate suggestive, and different minds may be likely to read different messages into them" (459). Many different readings have indeed been offered, some more valid than others.

Jan Marsh, a recent biographer, discusses the "many [. . .] autobiographical elements" in the poem (229). Another Rossetti biographer, Lona Mosk Packer, believes "no poem of hers is more clearly based upon personal experience" (141). Packer connects her interpretation of Goblin Market to her still unproved theory that the Pre-Raphaelite poet and painter William Bell Scott was the central albeit unrequited love of her life. Packer suggests that the line, "For there is no friend like a sister" (Complete Poems I: 26; all references to Goblin Market refer to this edition, hereafter cited as CP ), may refer to Christina's older sister, Maria, who may have warned Christina that Scott had fallen in love with another woman, one who was not his wife (Packer 150-51). Packer is on more solid ground when she writes: "Temptation, in both its human and its theological sense, is the thematic core of Goblin Market " (142).3

In 1950 John Heath-Stubbs rated Christina Rossetti's "artificial dream-world" in Goblin Market higher than the poetic worlds created by her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris from "older romance": "within its smaller compass, her world has more of the genuine life of the world or romance and folk-tale than theirs." Lizzie, Stubbs maintains, "may be taken as a type of the Christian as well as of Christ" (175). Expanding on this idea, Marian Shalkhauser writes: "Lizzie [. . .] is the symbol of Christ; Laura represents Adam-Eve and consequently all of sinful mankind." If the poem reenacts the Edenic myth, then "Satan appears typically in the form of depraved animals" (19), an idea that overlaps with my own interpretation.

Writing about the same time as Heath-Stubbs (in 1949), Marya Zaturenska seems to rate Goblin Market even higher than he does:

The mingling of the

grotesque

and the terrible, the sense

of the trembling innocence

that hovers on the abyss of

the unnamable and the

repulsive,

make this strange little

poem one of the masterpieces

of English literature as well

as a Pre-Raphaelite show

piece. (77)

A. A. DeVitis interprets the poem as "an allegory that on one level suggests the creative process that the artist herself may not have been aware of, a process that for Christina involved the renunciation of the passionate side of life" (420). Winston Weathers sees Goblin Market as "the prototypal poem in Christina's myth of the self [. . .] the two sisters [Laura and Lizzie] are aspects of one self [. . .]" (82). DeVitis adds that "Together the sisters make up the whole person who becomes the artist" (425).

Dorothy Mermin rather stridently disagrees. Critics such as Weathers and DeVitis, "By turning the two sisters into parts of one person [. . .] minimize or distort the central action in which one sister saves the other; they shy away from the powerful image of Lizzie as Christ" (107). Ellen Golub, on the other hand, carries Weathers' tentatively Freudian interpretation even further:

The poem's nuclear fantasy [.

. .] is the

conflict

between regressive

oral sadism and the

reality-testing anal stage which

battles for

prominence in normal development.

After an immersion in

total

sensuality and

non-responsibility, aggressive impulses are given

free

access

to discharge. By resolving the conflict, the poem also

unites warring

parts

of the self. In addition, it moves briefly to the

genital level at

which

both sisters have matured into wives and mothers. (164)

Another provocative Freudian interpretation that also fails to ring entirely true is that of Maureen Duffy. In The Erotic World of Faery, Duffy writes: "This [Victorian] double female image [of two sisters] is an interesting component of the period's eroticism akin to the heterosexual male desire to see blue films about lesbians or for similar themes in the work of Courbet, Lautrec or Schiele" (288-289). I agree to some extent that "the goblins represent animal instinct," but Duffy's assertion that Laura's "eating the fruit is a powerful masturbatory fantasy of feeding at the breast" (290) is, I think, wrong-headed and reductive. The various fruits are of course sexual, but they are offered by chthonic male creatures, and they are metonymical extensions of the goblins themselves, figures from the collective unconscious which I shall further discuss later.

I quite agree with Stephen Prickett that love is what Lizzie can bring back from the goblins to save Laura and that her "urging 'eat me, drink me, love me' is more than Christ-like, suggesting a passion that is almost incestuous." Christina Rossetti herself would have been conscious only of the required love, and Prickett is right to observe: "The hidden antithesis of Victorian prudery was, naturally, the flourishing sub-culture of pornography--which is first identifiable as a separate genre in Victorian times" (106). This fact perhaps accounts for Duffy's opinion which I've just quoted. Prickett further comments: "Like so many fantasies of the period, it is not difficult to find in The [sic] Goblin Market an image of the divided mind, and a divided society, terrified to come to terms with its own deepest needs and desires" (106). From the Jungian point of view, then, the poem compensates for contemporary prudery in its lush depiction of a sexuality that goes far beyond what the poet intended.4

Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar note that in Goblin Market Rossetti seems "to be dreamily positing an effectively matrilineal and matriarchal world, perhaps even, considering the strikingly sexual redemption scene between the sisters, a covertly (if ambivalently) lesbian world" (567). It is true that the only male characters in the poem are the goblins, but the psychic integration that the sisters achieve by the end of the poem comes partly because they have absorbed the masculine qualities of the goblins,5 and through the symbolism of same-sex love they have each achieved a psychic whole. Rossetti's creative process and the process and symbols of her characters' individuations are what I would like now to concentrate on.

II

In my book, The Stuff That Dreams Are Made On, I discuss Jung's theories of creativity (6-7). Suffice it to say here that Jung, echoing Plato, writes: "Art is a kind of innate drive that seizes a human being and makes him its instrument. The artist is not a person endowed with free will who seeks his own ends, but one who allows art to realize its purposes through him." The artist as a human being has a free will, of course, but

as an artist he is "man" in a higher sense--he is

"collective man,"

a vehicle and moulder of the unconscious psychic

life of mankind.

That

is his office, and it is sometimes so heavy a burden that he is

fated

to

sacrifice happiness and everything that makes life worth

living for the

ordinary human being. (CW 15: 101)

Jung refers here to artists whose work is "visionary"; that is, the work compensates through its archetypal imagery for contemporary psychic imbalance. Goblin Market, as I have suggested, falls into this category. Given the known facts of Christina Rossetti's life, one is tempted to class her as an artist who sacrificed "happiness and everything that makes life worth living for the ordinary human being." We know that twice she gave up marriage for religious reasons. She rejected James Collinson, a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, as a teenager of about eighteen, because of Collinson's Roman Catholicism; and she rejected, at about age 30, Charles Bagot Cayley because of his relative lack of religious faith (see M. Rossetti lii-liv). If we are to believe Lona Mosk Packer's theory, discounted by Marsh (119), Rossetti's actual love was William Bell Scott, who because he was married was unavailable. In any case, Rossetti's unhappiness in love could apparently be more readily blamed on her religion than on her vocation as a poet. However, even her religious faith, strong as it was, did not vanquish all doubts, as a close reading of her poetry will demonstrate. For her, life was the veritable "veil of tears." Her sonnet called "One Certainty" reflects the view and uses the language of Ecclesiastes:

Vanity of vanities, the

Preacher

saith,

All things are vanity. The

eye and ear

Cannot be filled with what

they see and hear.

Like early dew, or like

the sudden breath

Of wind, or like the grass

that withereth,

Is man, tossed to and fro

by hope and fear:

So little joy hath he, so

little cheer,

Till all things end in the

long dust of death.

Today is still the same

as yesterday,

Tomorrow also even as one

of them;

And there is nothing new

under the sun:

Until the ancient race of

Time be run,

The old thorns shall grow

out of the old stem,

And morning shall be cold and

twilight grey. (CP I: 72)

Nothing very original here, yet the poem does illustrate a typical attitude in Rossetti's poetry.6 Her famous renunciation of love (and some would include life) was due more to her religious faith than to her art.7

On the other hand, out of her deep pain came her brilliant work as an artist. I believe that, like Laura and Lizzie in her best poem, Christina Rossetti was an introverted-intuitive type. As Marie-Louise von Franz notes, "Many introverted intuitives are to be found among artists and poets. They generally are artists who produce very archetypal and fantastic material [. . .]" ("The Inferior Function" 33). Furthermore,

the introvert feels as if an

overwhelming object wants

constantly to

affect him, from which he has continually to retire

[. . .]

he

is constantly overwhelmed by impressions, but he is

unaware

that he is secretly borrowing psychic energy from and

lending it to the

object through his unconscious extraversion. ("The Inferior

Function"

1)

Moreover, "the introverted intuitive has particular trouble in approaching sex because it involves his inferior extraverted sensation" (35).8 Ironically, one's inferior function can open one up to ecstatic experience. Robert A. Johnson, for instance, writes: "Carl Jung says that the inferior function is always one's God connection" (58). Von Franz cites the example of Jakob Boehme, the German mystic who was an introverted-intuitive type, whose "revelation of the Godhead [. . .] came from seeing a ray of light being reflected in a tin plate. That sensation experience snapped him into an inner ecstasy and within a minute he saw, so to speak, the whole mystery of the Godhead" ("The Inferior Function" 36).

In ecstatic poems like "A Birthday," Rossetti

seems

to experience the same kind of breakthrough. Unfortunately for her

personal

life, but fortunately for poetry, she never fully developed her

sensation

function into a satisfactory love relationship, unlike Laura and

Lizzie.

Regarding Boehme, von Franz says: "To be crucified between the superior

and the inferior function is vitally important." Such conflict was

destroyed

for Boehme by a German baron who, after Boehme's first book was

published,

provided for Boehme's family, thus relieving him of that financial

burden

and at the same time allowing him to escape "the torture of his

inferior

function" (37). Von Franz implies, as does Jung, that suffering is

necessary

to produce great philosophy or art. It is necessary, in other words,

for

creativity. This is a large issue which time and space do not allow me

to develop fully here. In Christina Rossetti's case, however, the idea

that from suffering comes great art applies.9

William Michael Rossetti's comment that his sister's "habits of composition were entirely of the casual and spontaneous kind, from her earliest to her latest years" (lxviii) has stimulated much critical discussion. Thomas Swann comments: "Christina was not the craftsman her brother was. She wrote simply, often carelessly, and she did not like to revise." He also says: "The best whimsy is spontaneous and not the product of conscious artistry" (24; he feels Christina's whimsy is superior to that of her brother, Dante Gabriel, and the other Pre-Raphaelites). To contend that Christina Rossetti did not revise, was not a conscious artist, is quite simply wrong. As Packer and others have shown, she was a careful artist who conscientiously revised her work (see especially Antony Harrison 1-22). Virginia Woolf's centennial essay, "'I Am Christina Rossetti'," is perhaps the best description of Rossetti as an artist. Addressing the poet herself, Woolf writes:

I doubt indeed that you

developed very much.

You were an instinctive

poet. You saw the world

from the same angle always. [. .

.] Yet for all

its

symmetry, yours was a complex

song. When

you struck your harp many

strings sounded together.

Like all instinctives you had a

keen sense

of the visual beauty of the

world. [. . .] A firm

hand pruned your

lines; a sharp ear tested their music.

Nothing soft, otiose, irrelevant

cumbered your pages.

In a word, you were an

artist. (220)

Although her best work, including Goblin Market, may have arisen spontaneously from the unconscious, even as she wrote Rossetti applied consciously her craft as a poet. It could be no other way. Many critics have remarked on the eccentric meter and rhythm of Goblin Market, and many note how Rossetti adapts that rhythm to meet the requirements of the mood and/or imagery she is conveying. This is the work of a true artist.

III

Christina Rossetti lived in an era of renewed

popular

interest in myth, romance, legend, and fairy tales. Indeed, fairy

painting

became a "unique Victorian contribution to art," stimulated by this new

interest and, according to Jeremy Maas, a widespread interest in

spiritualism

(148). Maureen Duffy remarks: "Often in fairy paintings the subject

simply

provides an excuse for painting the naked female form" (291). But

Rossetti

objected to the depiction of naked fairies by her friend Gertrude

Thomson,

a "popular illustrator of children's books." Rossetti suggested to

Thomson

that "perhaps [. . .] women artists ought not to paint nudes"

(Zaturenska

245). Rossetti also refused to be caught up in the "fashionable

seances"

attended by her brothers, Dante Gabriel and William Michael, in 1864

(Packer

212).

Nevertheless, in poems such as Goblin Market, The Prince's

Progress, and in her children's books, Sing-Song (poetry,

1872)

and Speaking Likenesses(prose, 1874), she freely indulges in

fantasy

and fairy tale.

Speaking Likenesses is generally dismissed by those critics who bother to comment; and in fact Rossetti herself called the volume "merely a Christmas trifle, would-be in the Alice style with an eye to the market" (qtd. by Packer 305). Illustrated by Arthur Hughes, Speaking Likenesses contains three stories told by an "aunt" to several little girls. The first and longest story is about Flora's unhappy eighth birthday party from which she, like Alice, escapes by falling asleep. Flora walks down a "yew alley" and enters an enchanted house whose door knocker shakes hands with her and whose furniture is alive, rather like the furniture in television's Pee-Wee's Playhouse. The children in this Victorian fantasy playhouse come in shapes of quills, angles, hooks, and slime. The games the children play, "Hunt the Pincushion" and "Self-help," as one critic points out, "reveal a deep fear of sexual violence and a disturbing disrespect for humanity" (McGillis 227). "Hunt the Pincushion" is described thus:

Select the smallest and weakest player (if possible let her be fat: a hump is best of all), chase her round and round the room, overtaking her at short intervals, and sticking pins into her here or there as it happens: repeat, till you choose to catch and swing her; which concludes the game.

The narrating aunt adds: "Short cuts, yells, and sudden leaps give spirit to the hunt" (Speaking Likenesses 33).

The sexual connotations are clear, and the fact that the victim is female accurately portrays the woman's role in Victorian England so far as sex and romance are concerned, but taken as a whole, Rossetti's take-off on the Alice stories lacks the Carroll magic.

The same may be said for the other two stories. In the second story, the heroine is Edith, whose task is to get a kettle boiling. She fails, even with the help of a frog who can't boil the kettle either. The final story takes place in winter, unlike the previous two (the children, who carry on a running dialogue with the storyteller, ask for a "winter story," 70). Here Dame Margaret, owner of the "village fancy shop" (71) sends her granddaughter, Maggie, on a Christmas Eve errand to deliver "tapers" to a doctor's large house (74). Excited at the chance of seeing the doctor's Christmas tree, Maggie slips on a piece of ice, and then her adventures begin. She encounters scary children who want to play Hunt the Pincushion and Self-help. In brackets, one of the aunt's auditors, Ella, asks: "are these those monstrous children over again?" And the aunt replies: "Yes, Ella, you really can't expect me not to utilize such a brilliant idea twice" (78-81). One suspects the real reason for the repetition is a paucity of ideas. Maggie soon meets a horrid boy at whose heels "marched a fat tabby cat" with a tabby kitten in her mouth (84). The boy's face is all mouth and teeth, and, reversing the sex roles of Goblin Market, he demands of Maggie a piece of the chocolate she's carrying to the doctor's house. Whereas in Goblin Market the male goblins tempt the females with their fruit, here the female Maggie has the food the voracious male desires. She successfully resists him.

At the doctor's house, Maggie is not invited in to see the Christmas tree. However, on her way home she rescues a wood-pigeon, a "small tabby kitten" (93), and a puppy. They all arrive safely at Maggie's grandmother's house, where Maggie is received with a "loving welcoming hug" (95). Archetypally, Maggie has a healthy relationship with the positive and negative unconscious figures represented by the images of the mouthy boy and the helpless animals. One is somehow reminded of the Little Red Riding Hood story here, except that, of course, Granny is really Granny when Maggie arrives home; and Maggie has, as it were, already successfully encountered the menacing shadow/animus figure of the boy in the dark of the cold winter forest, symbolic of the unconscious. Like Laura and Lizzie, this child returns to the warmth and wholeness of a female world. Nevertheless, Speaking Likenesses is more in Jung's psychological mode than in his visionary mode. It speaks as much of Rossetti's personal psychology as it speaks of the Victorian age, and perhaps that accounts for its relative lack of popularity.10

Sing-Song, unlike Speaking Likenesses, was not written "with an eye to the market," yet it was one of Rossetti's most popular books, and remains so today. This fact suggests that, as is the case with Goblin Market, something in the book appeals to the collective psyche. Although at the time of its publication The Academy reviewed it with Carroll's Through the Looking Glass and Lear's More Nonsense (Packer 265), Sing-Song is hardly in the same category as these classics in terms of originality and archetypal appeal. Still, it is a pleasant, albeit often didactic, children's book. There are precious few nonsense verses à la Lear, very little of the trickster archetype. Blake's influence can be seen in such poems as the one that begins "Dancing on the hill-tops/Singing in the valleys" (Poetical Works 434) with its echo of Blake's "Piping down the valleys wild." But there is virtually none of Blake's wildness and numinous imagery. Rossetti shows a fondness for paradox ("A pin has a head, but has no hair; /A clock has a face, but no mouth there [. . .]" 432), and she exhibits an introverted attitude toward nature:

I have but one rose in the

world,

And my one rose stands

a-drooping:

Oh when my single rose is dead

There'll be but thorns for

stooping. (437)

Death, as in her other poetry, is a frequent theme (fairly ironic in

book for children).

Yet she has joyful, fanciful verses such as:

In the meadow--what in the

meadow?

Bluebells, buttercups,

meadowsweet,

And fairy rings for the

children's feet

In the meadow. (435)

Motherless and dead babies abound, reflecting not only contemporary reality but also a deep psychic need for the growth and wholeness offered by these symbols (mother and child) from the collective unconscious. The first edition, illustrated by Arthur Hughes, begins and ends with pictures of mother and child. The frontispiece shows them in an idyllic setting surrounded by sheep, birds, ponies, and a rabbit. Angels look on from the tree whose base the mother sits on, knitting, the baby in her lap.11 There are examples, too, of female threesomes such as we have in Goblin Market and poems like the sonnet, "A Triad." As we shall see, three is often a number of wholeness for the female.

Another motif in Sing-Song found frequently in Rossetti's other poetry is that of dreaming: "'I dreamt I caught a little owl/And the bird was blue---'" (440). To find examples from Rossetti's other work, one has merely to glance at the Table of Contents from her Complete Poems: "Dream-Land," "My Dream," "Dream-Love," for instance. Dreams are one of the chief sources of archetypal images, and the motif appears as well in Goblin Market: "Laura awoke as from a dream" (CP I: 25).

Goblin Market is so well known that a brief summary of the narrative seems almost superfluous. Two sisters, Laura and Lizzie, who live in the country, are tempted by goblin men to buy and eat their delicious, exotic fruits of many varieties. Although both intuitively understand that to eat would be deleterious (they have the example, too, of Jeanie, who died after eating the fruit), Laura succumbs to temptation by purchasing the fruit one night (symbolic of the unconscious) with a lock of her golden hair. Elisabeth G. Gitter has shown that for the Victorians golden women's hair had "powers both magical and symbolic," connected to both "wealth and female sexuality" (936). For Gitter, Laura's bartering her hair for the goblin fruit is obviously sexual (946). She gorges herself with great pleasure. The imagery here is clearly sexual.12 Laura

sucked their fruit globes fair

or red:

Sweeter than honey from the rock.

Stronger than man-rejoicing wine,

Clearer than water flowed that

juice;

She never tasted such before,

How should it cloy with length of

use?

She sucked and sucked and sucked

the more

Fruits which that unknown orchard

bore;

She sucked until her lips were

sore. . . . (14)

Laura is so immersed in the unconscious, she can't tell if it is "night or day. [. . .]" That the imagery suggests oral sex is appropriate since this is a tale about female same-sex individuation.

Fig. 2, drawing by D. G. Rossetti for the cover of Goblin Market

and Other Poems (1862), his sister, Christina's first book of

poems.

Now Laura can no longer hear the goblins call, though she addictively desires the fruit and her sister Lizzie does hear the goblins.13 Watching Laura slowly die, Lizzie goes to the goblins to buy some fruit in order to provide Laura with a cure. The goblins refuse to accept Lizzie's penny. She must eat the fruit herself. When she refuses, they attack her, smearing enough of the fruit juices on her face that Laura, upon Lizzie's pleading ("Eat me, drink me, love me [. . .]"), eats the now bitter juice and thus recovers. At a first reading, the "moral" of the tale, spoken by Laura, seems almost tacked on, not unlike the "morals" of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and The Picture of Dorian Gray :

"For there is no friend

like

a sister

In calm or stormy weather;

To cheer one on the tedious

way,

To fetch one if one goes

astray,

To lift one if one totters

down,

To strengthen whilst one

stands." (CP I: 26)

Katherine Mayberry feels the ending is necessary to "complete" Rossetti's "definition of her own poetics" (85). I have, however, another explanation. The closing statement by Laura demonstrates what she's learned about the salvific effects of sisterly sacrifice and love. Together the two sisters have accomplished their own individuation processes.

That the goblin men are archetypal images from

the

collective unconscious is clear from their power over the sisters'

imaginations,

especially over Laura's. As the noted Jungian psychologist James

Hillman

writes: "one thing is absolutely essential to the notion of archetypes:

their emotional possessive effect, their bedazzlement of

consciousness

so that it becomes blind to its own stance" (24, my italics).

"Bedazzlement" is the perfect word to describe the goblins' effect

after Laura has eaten of their fruit. Both Laura and Lizzie apparently

have superior intuitive functions to begin with. They both intuit the

dangers

of eating goblin fruit. Says Laura:

"We must not look at

goblin

men,

We must not buy their

fruits:

Who knows upon what soil

they fed

Their hungry thirsty roots?"

(12)

Lizzie agrees: "'Oh,' cried Lizzie, 'Laura, Laura,/You should not peep at goblin men'" (12). Yet, Eve-like, Laura cannot resist the sensuous feast offered by "each merchant man," described by Rossetti thus:

One had a cat's face,

One whisked a tail,

One tramped at a rat's pace,

One crawled like a snail,

One like a wombat prowled

obtuse and furry,

One like a ratel tumbled

hurry skurry. (13)

One is also "parrot-voiced and jolly" and "One whistled like a bird" (14).

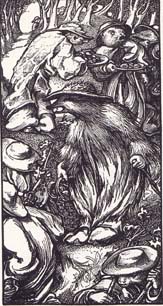

Although the description seems harmless enough, for most are cuddly, pet-like, androgynous animals such as Christina's brother, Dante Gabriel, might have kept (in fact did keep) in his private menagerie, these half-human/half-animal creatures are Victorian equivalents of such classical tricksters as satyrs, sileni, Pan, Priapus, Dionysus, Eros, and Hermes. The illustrations by Laurence Housman (brother of A. E. Housman) make clear their menacing quality in the edition published in 1893, the year before Rossetti's death (see Fig. 3).14 The animal imagery Christina Rossetti uses is not that of goats (or horses, also associated with sileni and centaurs), but their description matches that of satyrs and sileni given by Catherine Johns:

Both species were rural

spirits who, being half-animal,

were able to behave in ways which

would not have been

acceptable for humans. In effect,

they embody the animal

side of human nature, seen as a

separate quality. (82)

One of the animals, Rossetti mentions, the cat, is actually a close companion of Dionysus in the form of a panther, as well as of a tiger (Johns 84). One trickster trait is the ability to change genders, and Pan, son of Hermes and a companion of Dionysus, appears as both male and female in ancient art (44). Dionysus too is an androgynous god, raised as a girl to protect him from Hera (Johnson 6). Like the other Greek and Roman figures I've cited, Pan is a highly sexual being. He is often "depicted sexually accosting other deities, nymphs, shepherds and shepherdesses" (Johns 48).

Fig. 3, drawing by Laurence Housman for

the 1893 edition of Goblin Market.

Hermes, the Greek trickster, has the "gift of guile in sexual seduction" (Brown 13-14). Moreover, he is a guide, a "connection-maker," as Rafael López-Pedraza writes, an initiator "into the repressed unconscious nature" (7-8). Animals are part of his archetypal imagery (16). Eros, the Greek god of love, by the Roman era had become "a mischievous young boy, playing tricks on people and wounding them with his arrows [. . .] Like so many important deities, he had a dark as well as a light side; sexual passion can be a cruel and unrewarding experience" (Johns 54). Such is the case, at least initially, for Laura.

All of these mythological figures are associated with fertility. In fact, Priapus, known for his enormous phallus, is often pictured with fruit, "to demonstrate his function of ensuring the increase of crops" (Johns 50). Dionysus, of course, is a fertility symbol par excellence. One of the many fruits Rossetti cites in Goblin Market, the pomegranate, is associated with him, for a pomegranate tree, itself a fertility symbol, "sprouted from the earth where a drop of his blood had fallen" (Johnson 6).15 Pan and the satyrs are, as we know, closely connected to Dionysus. Indeed, the satyrs taught Dionysus the glories of dance and ecstatic sex (Johnson 7).

After eating the goblin fruit, Laura has become possessed, rather like a Victorian maenad, by the images of the goblins, and "possession," according to von Franz, "means being assimilated by [. . .] numinous archetypal images" (Shadow and Evil 128). Von Franz's description of a similar possession in a South American Indian folk tale describes Laura as well: she "has lost the instinct of self-preservation" (129): "Her hair grew thin and gray; / She dwindled, as the fair full moon doth turn / To swift decay and burn / Her fire away" (CP I: 18). The goblin men are, then, dual archetypes for the sisters. As malevolent, furry creatures with ambivalent sexuality, they symbolize the shadow; as male sexual creatures who represent unbridled fertility, sensuality, and sexuality, they are the negative animus for the two sisters.

Yet there is something positive they offer. They offer an approach to the inferior functions of both sisters. As intuitive types, their inferior function is sensation. If they can avoid being overwhelmed by this function and the archetypes from which it springs, they can gain a wholeness hitherto unknown to them. Laura has been pathologically overwhelmed. She has become addicted, as it were, to the sensual, sexual experience offered by the goblins,16 and she has immediately reached the stage that for most addicts comes much later--the stage in which the addictive substance no longer "works," no longer provides the desired high. Instead, it threatens to kill her. Sometimes the cure for addiction (including alcoholism) starts with a last dose of the substance to help the addict through withdrawal. Lizzie intuitively understands this. Jung has stated, in a letter to one of the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous, William G. Wilson, that the alcoholic's

craving for alcohol [. . . is]

the equivalent on a low level

of the

spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in

medieval

language:

the union with God [. . .] alcohol in Latin

is spiritus and you

use the same word for the highest religious

experience as well as for

the

most depraving poison. (Selected Letters 198)

The "cure" for alcoholism is the same cure Laura needs: a spiritual experience, a redemption in short. (That Dionysus is the god of wine is worth noting here; the goblin fruit is said to be "Stronger than man-rejoicing wine," 14.) This redemption is not possible till she reaches a "bottom" such as addicts and alcoholics must reach before recovery. Once she has experienced the depths, Laura is ready for the "salvation" Lizzie offers.

Lizzie, however, to complete her own, less drastic, individuation process, must also experience the shadow and negative animus. She has developed enough of the rational, thinking function to attempt to bargain with the goblin men by offering them money. They will have none of this, so they attempt to rape her:

They trod and hustled

her,

Elbowed and jostled her,

Clawed with their nails,

Barking, mewing, hissing,

mocking,

Tore her gown and soiled

her stocking,

Twitched her hair out by

the roots,

Stamped upon her tender

feet,

Held her hands and squeezed

their fruits

Against her mouth to make

her eat. (21)

Lizzie resists, "like a lily in a flood [. . .] like a beacon left alone / In a hoary roaring sea, / Sending up a golden fire,-- / Like a fruit-crowned orange-tree / White with blossoms honey-sweet / Sore beset by wasp and bee,--" She is also compared to "a royal virgin town / Topped with gilded dome and spire / Close beleaguered by a fleet / Made to tug her standard down" (22).

While many of the images are those of the female (the "lily" or "dome," for example) besieged by the ravenous male, some are those of the male (the "beacon" or the "spire") threatened by the devouring female. The psychological point is that Lizzie must experience the negative sides of both the female (the shadow) and the male (the animus) before she can be whole enough to rescue Laura. She must also absorb the positive sexual and creative energy represented by the chthonic goblins.

The imagery Rossetti uses here is both religious and sexual.17 Lizzie says to Laura:

"Hug me, kiss me, suck my

juices

Squeezed from goblin fruits

for you,

Goblin pulp and goblin dew.

Eat me, drink me, love me;

Laura, make much of me:

For your sake I have braved

the glen

And had to do with goblin

merchant men." (23)

Laura heeds Lizzie:

She clung about her

sister,

Kissed and kissed and kissed

her:

Tears once again

Refreshed her shrunken eyes,

Dropping like rain

After long sultry drouth;

Shaking with aguish fear,

and pain,

She kissed and kissed her

with a hungry mouth. (24)

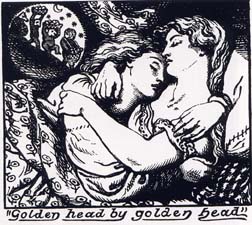

Rossetti describes and prescribes the same kind of same-sex union Plato proposes in the mouth of Aristophanes in the Symposium. Earlier Rossetti had shown the two sisters as two halves of the same whole:

Golden head by golden

head,

Like two pigeons in one

nest,

Folded in each other's

wings,

They lay down in their

curtained

bed:

Like two blossoms on one

stem,

Like two flakes of

new-fall'n

snow,

Like two wands of ivory

[. . .] (16; see fig. 2)

William Rossetti has attested to the fact that Plato was among Christina's favorite authors: "she read his Dialogues over and over again" (PW lxx); yet the idea that she would consciously depict lesbian love as a means to wholeness and redemption is of course out of the question. Nevertheless, she may have unconsciously depicted the union of the two primal female halves "each desiring his other half" (Plato 335) like the primal male-male and male-female human beings in Plato's myth. Not surprisingly, Plato uses traditionally Western symbolism for these primal sexes: "the man was originally the child of the sun, the woman of the earth, and the man-woman of the moon, which is made up of sun and earth" (335). Laura and Lizzie have each assimilated and accommodated the contrasexual as well as developed their inferior sensation functions and thus found in themselves their own individual Selves, which include vital connections to the earth, as well as motherhood and creativity. Lizzie demonstrates creativity in her dramatic rescue of Laura, who becomes an artist, a storyteller.

If any further evidence is required to demonstrate Goblin Market is a poem about female psychic integration, one need only examine Rossetti's conscious and unconscious use of the numbers three and four. As I have indicated, there are three females in the poem: Laura, Lizzie, and the late Jeanie. The "plot," Katharine Briggs observes, "is a variant of three main fairy themes: the danger of peeping at the fairies, the taboo against eating fairy food, and the rescue from Fairyland" (193). Now, although the number four is generally the number of wholeness in Jungian thought, the number three, when it appears in its "threefold aspect as maiden, mother, and Hecate [. . . the Kore figure, in short] has her psychological counterpart," Jung writes, "in those archetypes which I have called the self or supraordinate personality on the one hand, and the anima on the other" ("Psychological Aspects of the Kore" 182). The myth of Demeter and her daughter Persephone (also called Kore), who is abducted by Hades and must spend a third of the year with him in the underworld after having eaten a pomegranate seed, is well known. Here we have another set of three, three mythological seasons as opposed to the usual four. Demeter, the mother, is also Hecate, the moon goddess (see Kerényi 109-120), the female shadow, and with Persephone she makes a whole female Self.

The tripartite female is clearly portrayed in Goblin Market. All three women--Laura, Lizzie, and Jeanie--are maidens. Jeanie, a victim of the shadow (the goblins and their fruit are both male and female, as we have seen), never realizes the Self. Laura and Lizzie, on the other hand, experience, as I have demonstrated, the archetypal shadow, both personal and collective. Each in different measure experiences the "forbidden fruit" of sexual knowledge, albeit Lizzie never indulges fully as does her sister. By the end of the poem, both have become mothers: "wives / With children" (CP I: 25). Some of the numinous power of their experience lingers as Laura tells her "little ones" of "her early prime, / Those pleasant days long gone . [. . .]" As more than one critic has observed, she has become an artist, a storyteller, and she tells the story of "the haunted glen, / The wicked, quaint fruit-merchant men, / Their fruits like honey to the throat / But poison in the blood [. . .]" (25). She looks back with a mixture of nostalgia and regret, with feeling, in other words. Her final aphorism: "There is no friend like a sister" (26), shows that she's developed the thinking function (already developed, as we've seen, in Lizzie). The most developed or "differentiated," to use the technical term, function for both sisters has been the traditionally "feminine" intuition function. Of the inferior function (sensation for Laura and Lizzie), Jung writes: "Because of its contamination with the collective unconscious, it possesses archaic and mystical qualities, and is the complete opposite of the most differentiated function" ("A Psychological Approach to the Trinity" 121). Here the problem of the fourth is solved, for the sisters have, at least to some degree, developed all four functions of consciousness. The sensation function continues to be the weakest, but it has opened the door to individuation for both sisters, the equivalent of a "mystical" experience. When Laura awakens from her near-death nightmare, her hair is no longer gray, "Her breath was sweet as May / And light danced in her eyes" (25).

Although the sisters have married, their husbands play no part in the poem; they are neither seen nor named. Laura and Lizzie's most important relationship has been with each other. And it is clearly an erotic relationship that has brought them peace and psychic integration. Von Franz believes that Jung, in his Memories, Dreams, Reflections , implies "that a preconscious spiritual order lies at the base of all love relationships" (Number and Time 293), and she speaks of "an all-uniting Eros" (292). It is, then, the archetype of love which has transformed the lives of both Laura and Lizzie in Christina Rossetti's finest poem.

Notes

1Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar note, for instance, that Goblin Market "has recently begun to be something of a textual crux for feminist critics" (566). See Katherine J. Mayberry (16). Also, Jan Marsh's biography, Christina Rossetti, has recently appeared.

2Here I disagree with some critics. Elizabeth Jennings, for instance, declares that "Goblin Market, though it is often set before children at school it is not, to my idea, a poem for young people at all; it is an adult, short epic which happens to make use of fairies and goblins" (10).

3It is true that Goblin Market was dedicated to Maria Francesca Rossetti. The best William Michael could come up with by way of explanation was the following: "apparently C. [Christina] considered herself to be chargeable with some sort of spiritual backsliding, against which Maria's influence had been exerted beneficially" (qtd. by Packer 150). No one has been able definitively to establish exactly what Christina might have owed to her sister Maria, who did indeed seem to have a firmer faith and who near the end of her life became an Anglican nun (Packer 304-305).

4Christina Rossetti herself was, not surprisingly, a prude. William Michael Rossetti writes that she was "barely eighteen" when she gave up theater of any kind: "not perhaps that she considered plays and operas to be in themselves iniquitous, but rather that the moral tone of vocalists, actors, and actresses is understood to be lax, and it behoves a Christian not to contribute to the encouragement of lax moralists" (Poetical Works lxvi). She was, on the other hand, extremely tolerant of those, like her brother Dante Gabriel and Algernon Charles Swinburne, whose life styles she disapproved of. "Judge not, that ye be not judged" was the "precept of the Christian religion" she lived by (ibid. lxvii). Despite her tolerance for her relations and friends, she privately expurgated her own copy of Swinburne's Atalanta in Calydon by pasting "strips of paper over the lines in the atheistic chorus" (Packer 353).

5I owe this idea to my colleague at California State University, Long Beach, Donald J. Weinstock.

6In addition to Goblin Market itself, a famous exception is "A Birthday," of which the first stanza goes:

My heart is like a

singing

bird

Whose nest is in a watered

shoot;

My heart is like an apple

tree

Whose boughs are bent with

thickset fruit;

My heart is like a rainbow

shell

That paddles in a halcyon

sea;

My heart is gladder than

all these

Because my love is come

to me. (CP I: 36).

7Jerome J. McGann observes that for Rossetti "Erotic love must either be renounced altogether--an unimaginable project in itself--or it must be translated into forms of desire which are equally unimaginable or unspeakable" (14).

8I refer here to Jung's theory of the four functions of consciousness. Thinking and feeling are rational responses to the world, the first through one's intellect, the second through the unconscious. Feeling relates to values. Intuition and sensation are irrational functions. They perceive either through the unconscious (intuition) or through the conscious (sensation). See Snider 12-14.

9As a practicing poet, I have been on both sides of this issue. I must say, though, that my best work has never been deliberately willed; rather, it has come from an inner impetus that is largely outside my conscious control. Examples of suffering artists are far too numerable to mention, and, although I do not believe in the Freudian theory of sublimation, I do believe that some kind of psychic tension is necessary to produce lasting art.

10Perhaps the most striking archetypal image in the book is Arthur Hughes's illustration for the "Apple of Discord" which the children at Flora's birthday party fight over. The Apple is depicted as a pointy-eared, bare-breasted, medusa-like woman with snakes in her long Pre-Raphaelite hair. A scowl on her face, an apple in her right hand, and a long dagger in her sash, she towers threateningly over the children (11).

11Sing-Song i. Rossetti herself approved of Hughes's drawings. She wrote to her brother, Dante Gabriel:

What a charming design is

the ring of elfs [sic] producing the

fairy ring--also the apple

tree casting the apples--also

the three dancing girls

with the angel--kissing one--

also I liked the crow-soaked

grey stared at by his

peers. (qtd. by Zaturenska

195)

Notice the "fairy ring" (the verse is quoted above), another symbol, like the mother and child, for wholeness. The "three dancing girls" refers to the poem that begins: "Sing me a song--/What shall I sing?--/Three merry sisters/Dancing in a ring [. . .]" (Sing-Song 73), an example of a set of three females (with a fourth, the angel, making a whole) and a mandala--the ring.

12Marsh has a fairly balanced, albeit incomplete, discussion of the sexual imagery in Goblin Market. She concludes that "at some level . . . the sexual dimension was intentional. [. . . but] her deployment of erotic feeling in Goblin Market was [. . .] largely unconscious, derived from childish memories of sensual desire and perhaps other arousals" (234).

13Ellen Moers has made a similar observation: "Gorged on goblin fruit, Laura craves with all the symptoms of addiction for another feast, but craves in vain, for the goblins' sinister magic makes their victims incapable of hearing the fruit-selling cry a second time." For Moers, "'Suck' is the central verb of Goblin Market; sucking with mixed lust and pain is, among the poem's Pre-Raphaelite profusion of colors and tastes, the particular sensation carried to an extreme that must be called perverse." Moers concludes "that Christina Rossetti wrote a poem, as Emily Brontë wrote a novel, about the erotic life of children" (102).

14In the more famous illustrations by Christina's brother Dante Gabriel, the goblins are also menacing creatures, but the picture of Laura and Lizzie lying down and embracing asleep is the more remarkable for what it reveals about their relationship (see Fig. 2). An edition with color illustrations by George Gershinowitz published in 1981 emphasizes the human, sensual side of the goblins, as well as their menacing quality.

15Winston Weathers also sees a symbolic connection with the goblins and Dionysus, referring to "the deep, archetypal, even primordial freedom" he represents, at least in the paradigm posited by Nietzsche (83).

16In her brief Jungian analysis of Goblin Market, Gwen Mountford too sees the "fatal fruit" as "addiction." For Mountford, the poem is about "animus taking over in the field of a woman's sensuality" (68). Mountford, who also analyzes Virginia Woolf's Orlando , is heterosexist, as well as shallow, in her interpretations. She totally ignores the symbolism of same-sex love in both Rossetti and Woolf.

17Rod Edmond comments: "The fusion of eucharistic and sexual language in this scene makes it one of the most powerful in the poem, and it dominates the final sections" (185).

Briggs, Katharine Briggs. An Encyclopedia of Fairies:

Hobgoblins,

Brownies,

Bogies, and other Supernatural Creatures . New

York:

Pantheon, 1976.

Brown, Norman O. Hermes the Thief . 1947. Great Barrington,

MA:

Lindisfarne, 1990.

DeVitis, A. A. "Goblin Market : Fairy Tale and Reality." Journal

of Popular

Culture 1 (1968): 418-426.

Duffy, Maureen. The Erotic World of Faery . London: Hodder

and

Stoughton,

1972.

Edmond, Rod. Affairs of the Hearth: Victorian Poetry and Domestic

Narrative. London: Routledge, 1988.

Gilbert, Sandra M. and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic:

The

Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century

Imagination

. New

Haven: Yale UP, 1979.

Gitter, Elisabeth G. "The Power of Women's Hair in the Victorian

Imagination."

PMLA

99 (1984): 936-954.

Golub, Ellen. "Untying Goblin Apron Strings: A Psychoanalytic

Reading

of

'Goblin Market'." Literature and Psychology

25 (1975): 158-65.

Harrison, Antony H. Christina Rossetti in Context . Chapel

Hill:

U of

North Carolina P, 1988.

Heath-Stubbs, John. "Pre-Raphaelitism and the Aesthetic Withdrawal."

The Darkling Plain . London: Eyre and

Spottiswoode,

1950. 148-78.

Rpt. in Pre-Raphaelitism: A Collection of

Critical

Essays . Ed.

James Sambrook. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1974.

166-85.

Hillman, James. A Blue Fire: Selected Writings . Ed. Thomas

Moore.

New York: Harper, 1989.

Jennings, Elizabeth. Introduction. A Choice of Christina

Rossetti's

Verse.

By Christina Rossetti. London: Faber,1970. 9-12.

Johns, Catherine. Sex or Symbol: Erotic Images of Greece and Rome

.

Austin: U of Texas P, 1982.

Johnson, Robert A. Ecstasy: Understanding the Psychology of Joy.

San

Francisco: Harper, 1987.

Jung, C. G. "A Psychological Approach to the Dogma of the Trinity."

1948.

Psychology and Religion: West and East.

2nd Ed. Trans. R.

F.C.

Hull. 107-200. Vol. 11 of The Collected

Works of C. G. Jung . (CW )

Ed. Sir Herbert Read, Michael

Fordham,

and Gerhard Adler.

20 Vols.

---. "The Psychological Aspects of the Kore." 1941. The

Archetypes

and the

Collective Unconscious . 2nd ed. Trans. R. F.

C. Hull.

Princeton: Princeton UP, 1969. 182-203. Vol.

9, part i of CW .

---. "Psychology and Literature." 1950. The Spirit in Man, Art,

and

Literature.

Trans. R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton UP,

1966.

84- 105. Vol. 15 of CW.

---. Selected Letters of C. G. Jung, 1909-1961 . Ed. Gerhard

Adler.

Princeton: Princeton UP, 1984.

Kerényi, C. "Kore." Essays on a Science of Mythology

.

By C. G. Jung and

C. Kerényi. Trans. R. F. C. Hull. Princeton:

Princeton UP, 1963.

101-55.

López-Pedraza, Rafael. Hermes and His Children .

Einsiedeln,

Switzerland:

Daimon Verlag, 1989.

Maas, Jeremy. Victorian Painters . New York: Harrison House, 1969.

Marsh, Jan. Christina Rossetti: A Writer's Life. 1994. New York: Viking, 1995.

Mayberry, Katherine J. Christina Rossetti and the Poetry of

Discovery

.

Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1989.

McGann, Jerome J. "Introduction." The Achievement of Christina

Rossetti

.

Ed. David A. Kent. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1987. 1-19.

McGillis, Roderick. "Simple Surfaces: Christina Rossetti's Work for

Children."

The Achievement of Christina Rossetti.

Ed. David A. Kent. Ithaca:

Cornell UP, 1987. 208-30.

Mermin, Dorothy. "Heroic Sisterhood in Goblin Market ." Victorian

Poetry

21 (1983): 107-118.

Moers, Ellen. Literary Women . Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1976.

Mountford, Gwen. "Portrait of Animus." Harvest No. 25 (1979): 59-69.

Packer, Lona Mosk. Christina Rossetti. Berkeley: U of California P, 1963.

Plato. The Republic and Other Works . Trans. B. Jowett.

Garden

City, NY:

Dolphin Books, 1960.

Prickett, Stephen. Victorian Fantasy . Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1979.

Rossetti, Christina. Goblin Market. Illustrated by Laurence

Housman.

1893.

New York: Dover, 1983.

---. Goblin Market. Illustrated by George Gershinowitz.

Boston:

David R.

Godine, 1981.

---. The Complete Poems of Christina Rossetti. Ed. Rebecca W.

Crump. 2 vols. to date. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana State UP, 1979-85.

---. The Poetical Works of Christina Georgina Rossetti. Ed.

William

Michael Rossetti. London: Macmillan, 1904.

---. Sing-Song: A Nursery Rhyme Book. Illustrations by

Arthur

Hughes. 1872. Ann Arbor:

University Microfilms, 1966.

---. Speaking Likenesses . Illustrations by Arthur Hughes.

London:

Macmillan, 1874.

Rossetti, William Michael, ed. The Poetical Works of Christina

Georgina

Rossetti. London: Macmillan, 1904.

Shalkhauser, Marian. "The Feminine Christ." Victorian Newsletter 10 (1956): 19-20.

Snider, Clifton. The Stuff That Dreams Are Made On: A Jungian

Interpretation

of Literature.

Wilmette, IL: Chiron, 1991.

Swann, Thomas Burnett. Wonder and Whimsy: The Fantastic World of

Christina Rossetti. Francestown, NH: Marshall

Jones, 1960.

von Franz, Marie-Louise. "The Inferior Function." Lectures on

Jung's

Typology . By Marie-Louise von Franz and

James Hillman. Zürich:

Spring, 1971. 1-72.

---. Number and Time: Reflections Leading toward a Unification

of

Depth

Psychology and Physics . Trans. Andrea Dykes.

Evanston: Northwestern UP, 1974.

---. Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales. Dallas: Spring, 1974.

Weathers, Winston. "Christina Rossetti: The Sisterhood of Self." Victorian Poetry 3 (1965): 81-89.

Woolf, Virginia. "'I Am Christina Rossetti.'" The Second Common

Reader.

1932.

New York: Harcourt, 1960. 214-221.

Zaturenska, Marya. Christina Rossetti: A Portrait with Background.

New

York: Macmillan, 1949.

--Copyright © Clifton Snider, 2002. This article may not

be used without permission from the author.