Introduction

by

Wendy Griffin

Introduction

by

Wendy GriffinIntroduction by Wendy Griffin

When American feminist magazines ran articles on the budding Goddess Spirituality movement in the mid- to late '70s and early '80s, the information was largely limited to those feminists who either subscribed or borrowed copies of these magazines. When newspapers in California began to carry feature stories on Witches and Goddess groups in the late '80s, people attributed it to the reputation California has for attracting eccentrics.(1) In 1992, Elle, an upscale American women�s magazine, ran a feature titled �Goddesses, Gaia and the Witch Next Door,� and more people began to take notice. Even more took note when the extremely popular newsmagazine Time ran an article on Witches in the heartland of Wisconsin and reported a possible 100,000 adherents nationwide. Public attention increased dramatically when famed television evangelist Pat Robertson denounced a proposed equal rights amendment to the Iowa state constitution by saying it was part of a "feminist agenda. . .a socialist, anti-family political movement that encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism and become lesbians� (Goodman 1992). And during the American visit of Pope John Paul II, when he censured women�s involvement in the worship of an earth goddess and the celebration of her myths and symbols, something that conservative American clerics had already identified with Witchcraft (Cowell 1993), Goddess Spirituality made newspapers all over the country.The problem was that few outside the community of Goddess celebrants really knew what Goddess Spirituality was. Although thealogical explorations (thea meaning female divinity) had been published and a considerable number of books and journals by practitioners had appeared that dealt with everything from revisionist history to spell-casting, academic research on the practice itself was extremely limited. It still is. In Britain, the story is not that different. Even though some aspects of the movement are older in the United Kingdom, only a few British academics have published in this field.

This is true in spite of clear evidence that the movement has grown and continues to grow at a rapid rate. Gnosis, an American journal of mystery traditions, recently reported a population of up to 500,000 in the US Goddess community (Smoley 1998). Academic scholar Ronald Hutton (1998) suggests that the United Kingdom has between 110,000 and 120,000.(2) In some cases, research in this area has been actively discouraged. One colleague was advised to not put an article she had published on Goddess Spirituality into her tenure review file because the topic was �questionable.� Fundamentalist Christians picketed a presentation she gave on her research. Another was told to take the word �Goddess� out of the title of a book she was working on, as "the Goddess was passé.� Funding for doing research into religious and spiritual groups in general is typically hard to come by, unless, of course, these groups are suspected of being dangerous cults threatening to kidnap children or kill themselves and others. Funding for research into Goddess Spirituality is especially difficult to obtain. This may be particularly ironic, as most practitioners of Goddess Spirituality believe it is a serious threat to traditional religions and customs, not in the way that most people expect, but in its insistence on using very different frameworks of meaning and its reconstruction of gender and identity.

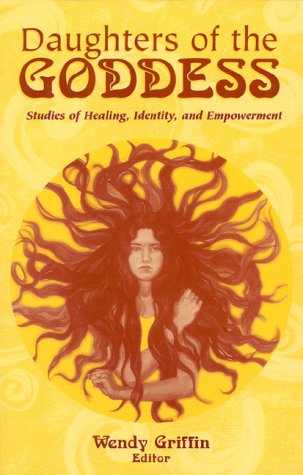

Who are the Daughters of the Goddess? They are women in the United States and Britain who may call themselves Witches, neo-pagans, pagans, Goddesses, Goddess women, spiritual feminists, Gaians, members of the Fellowship of Isis, Druids, and none of these names. (3) They practice Wicca, Witchcraft, the Craft, Women�s Mysteries and Earth Mysteries; they worship and celebrate in covens, large community rituals, and alone in front of their household or garden altars. They are housewives, students, teachers, secretaries, therapists, graphic designers, accountants, scholars, civil servants, travel agents, truck drivers, soccer moms, and some are even musicians performing in mainstream churches for a living. They are women who use female imagery in exploring and celebrating the Divine, and who see the Goddess as primary and immanent, encompassing all things, as the source and substance of being.(4) They are women involved in a new naming of reality.

In planning Daughters of the Goddess, I took into consideration the argument that the boundaries between many academic disciplines are artificial and a fuller understanding of the human experience can be achieved by refusing the limitations inherent in using just one perspective to study a particular cultural phenomenon. The academic researchers in this book come from the fields of anthropology, English, history, psychology, religious studies, sociology, and women�s studies. In addition to multidisciplinary perspectives, I have included several academic authors from Britain. Though variations in emphases of belief and practice exist on either side of the ocean, the contemporary story of what has become known as Goddess Spirituality has one of its major tap roots in Britain, and to ignore that would be to lose the depth that gives perspective its vision.

Along with the rich offerings to be found in these ethnographies, in-depth interviews, surveys, conversations, written materials, and corresponding analyses, I felt it important to include the voices and visions of a small sample of women who are not academics, but who are actively engaged in teaching a variety of forms of Goddess Spirituality. These women are among those who are creating the rituals, conducting the workshops and authoring the books that practitioners devour and we academics refer to in our writing. They are giving birth to contemporary images of female divinity that resonate with growing numbers of women and men. These three women have been selected because, in very different ways, they teach women to �heal and be healed� and �become the Goddess.� Although they are not among the most famous of Goddess teachers, through their workshops, community rituals and writings, these three authors have reached thousands of women.

The inclusion of their voices serves several purposes. In the debate about objective scholarship and privileged knowledge, this can be used as a device to compare epistemologies and raise questions about the nature of understanding. Clearly both their methodology and knowledge base differ dramatically from those of the academic authors, some of whom are also practitioners. In addition, it is important to understand the fluidity of practice that is permissible in Goddess Spirituality because it lacks a sacred, authoritative text. In our culture, reverence for the written word, the Word, often leads us to ignore the physical, subjective side of religious or spiritual experience. But Goddess Spirituality is radically embodied; to totally ignore experiential knowledge would be to dramatically and unnecessarily limit our understanding of the phenomenon. The voices of this second group of authors provide an alternative way to learn the kinds of things that practitioners learn and what they believe they are capable of experiencing.

The predominate theme weaving in and out of all the chapters in this book is one of wholeness of self and the power to define exactly what that self is. Healing the split between mind and body, feminist and Pagan, sexuality and spirituality, nature and human, and ancient and contemporary understandings of the Numinous is seen as healing the wounds believed to be inflicted by patriarchy. It is this process in Goddess Spirituality that appears to allow the possibility of creating a post-Christian, post-patriarchal, multifaceted and integrated identity.

In 1994, Witches in Bristol, England, declared that patriarchy was dead. It may indeed be dying, and certainly the research and teachings in Daughters of the Goddess suggest that significant social revisioning is taking place in both the U.K. and the U.S., an example of what New Religious Movements scholar Wade Roof Clark calls, �seethings of the spirit� (1998:12). Of course, even if the life and spirit have departed from patriarchal frameworks of meaning, the body has not finished thrashing about in its death throes. But as the old reality begins to lose its hold, a new reality is taking shape. * * *

The process reminds me of a weekend I spent with Witches several years ago camping in the mountains outside Los Angeles. We hiked to a small spring that bubbled out at the foot of a granite boulder. The large rock was vaguely human-like in shape. One woman climbed to the top of it and placed there a wreath she had woven out of yellow wildflowers. Another spontaneously took red berries and tucked them into cracks and crevices in the stone. Over the weekend, individual women would follow the trail to the spring, many adding leaves, flowers, pine cones and other offerings. With each addition, the shape in the rock became clearer, until it was no longer just a boulder. Pine needles outlined the curve of an arm, wild sage drew the eye to what could have been a pregnant belly, yellow flowers to flowing hair. With each visit, each offering, the Goddess of the Spring emerged from the rock and became more visible, more real.

With each woman, each ritual today, Goddess Spirituality contributes to the new reality that is taking form. This book explores the shaping.

Notes:

(1) Throughout the book, I have capitalized the word Witch as I would Christian, the word Witchcraft, Wicca or Craft as I would Judaism, the word Gaian as I would Muslim.

(2) Census figures for the U.S. suggest a current population of approximately 270,540, 000 (http:www.census.gov/cgi-bin/popclock). For the U.K., the latest figures amount to 58,660,000 http://www.statistics.gov.uk/stats/ukfigs/pop/htm/). Given both, these numbers reflect relatively equal percentages.

(3) Although male practitioners of Goddess Spirituality also exist, female participants vastly outnumber male, especially in the U.S..

(4) While some women and men also acknowledge a male divinity, the Goddess is always primary.

Works Cited:

Clark, Wade Roof. 1998. Religious borderlands: challenges for future study. Journal for the Scientific

Study of Religion. Vol. 37, No. 1, March. Pages 1-14.

Cowell, Alan. 1993. Pope issues censure of �nature worship� by some feminists. The New York Times.

July 5, Pages 1,4,6.

Goodman, Ellen. 1992. The ERA is back - older, wiser and playing to win. The Los Angeles Times.

October 20.

Hutton, Ronald. 1992. Personal Communication, September 2.

Smoley, Richard. 1998. The old religion. Gnosis. No. 48, Summer. Pages 12-14.

If any part of this introduction is quoted, Daughters of the Goddess: Studies of Healing, Identity and Empowerment. Wendy Griffin, Editor. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2000, must be cited.