Copyright © Brent C.

Dickerson

I would like to warmly thank California State University, Long Beach, for generously hosting this site dedicated to fostering an understanding of the people, conditions, and ethos of an earlier period of our area. These materials, to be developed, elaborated, edited, and updated continuously, are provided to enrich peoples' understanding of a short period of pre-Yankee California, and deepen the understanding and broaden the background for readers of my book Narciso Botello's Annals of Southern California 1833–1847, as well as to supply corrections or "fine-tuning" arising from further research. All materials on this site respect copyright law and the doctrine of fair use; should anyone know anything to the contrary concerning a specific item, please have the person in possession of the rights on the particular item or items contact me at once so I can remove the material in question. The drawings, and details of drawings, by William Rich Hutton which appear on this site are here by very special and specific courtesy of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California; requests concerning any further use of these images by Hutton must be made to not me but rather the Huntington Library. While other images on this site have in many cases had enhancements or changes of one sort or another for æsthetic or historical reasons (in other words, to "fix" blemishes, or to alter the view to something more specific to what Botello would have seen), these images of Hutton's are presented as drawn, in their current state, with at most a few pixels cropped around the perimeters to provide a smooth-looking edge to the images. Those wishing to contribute corrections or other matter relating to Botello's text and the California or Mexico of its time are not only welcome to contact me—they are encouraged to do so via e-mail at odinthor@csulb.edu. Please include the source of the data supplied, and, if applicable, if it is under copyright. Contributors should indicate in their messages whether they wish their names to be included should the material be published on this site. Materials provided will be regarded as being supplied voluntarily and gratis, with no anticipation of monetary compensation. Current representatives of the families which take part in Botello's narrative, or those which were present during the time of his narrative, are also encouraged to contact me with pertinent information, including family stories, about their ancestors and their ancestors' doings. As in the book itself, notes are referenced by the number of the paragraph in Botello's text in which the item in question occurs. Many thanks to Franklin G. Mead, descendant of the old Angeleno families Cota (Maria Luisa Cota) and Rosas (Jose Antonio Basilio Rosas), for his great help in catching many of these typographical errors!

• This section refers to Botello's text:

¶ 1.

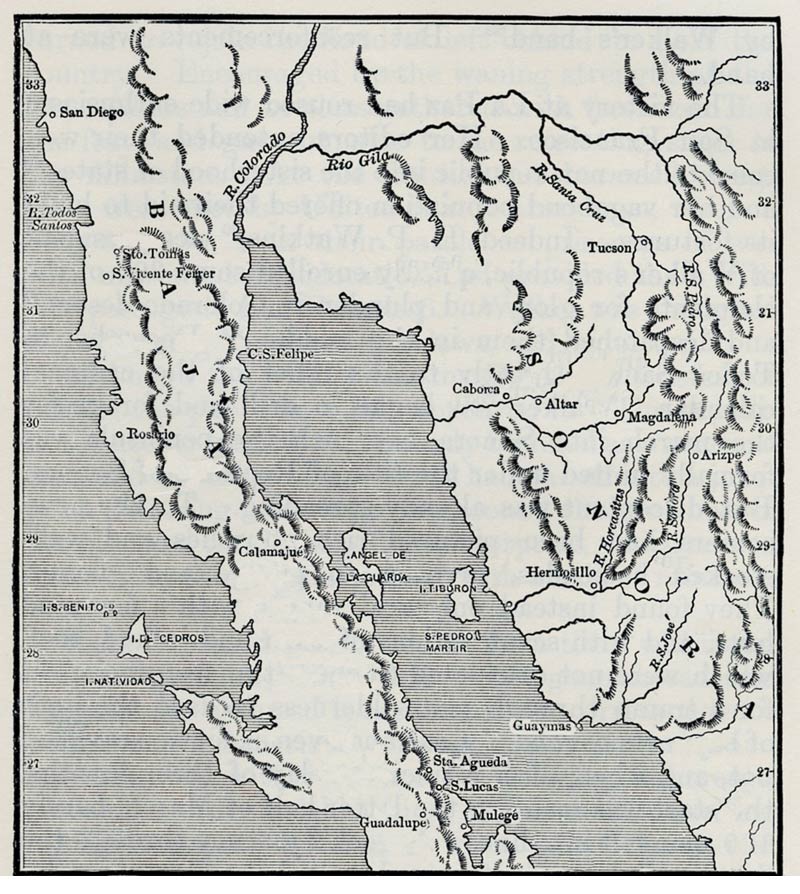

–A map of a portion of Baja

California and Sonora, showing the area of Botello's initial

travels (developed from an original map in Bancroft's History of

California).

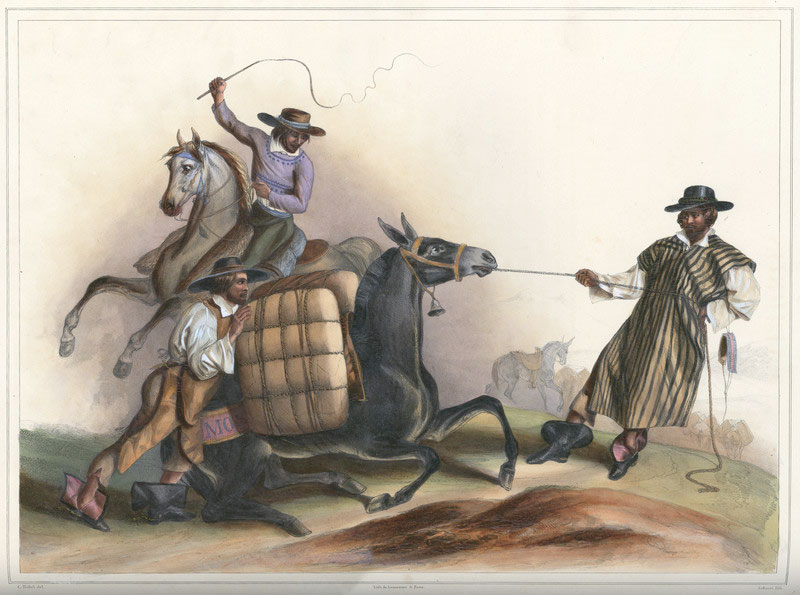

–The pleasures of overland travel in 1830s Mexico. Plate by Carl Nebel entitled Arrieros, from Voyage Pittoresque... of 1836.

¶ 2.

–Guaymas:

Some description of Guaymas from the mid- to late-1820s, when it would

have been familiar to Botello, this from R.W.H. Hardy's Travel in the

Interior of Mexico, pp. 89-91. "We arrived at the port of Guaymas on

the 8th February. The harbour is, beyond all question, the best in the

Mexican dominions: it is surrounded by land on all sides, and protected

from the winds by high hills. It is not very extensive, nor is the water

above five fathoms deep abreast of the pier; but there are deeper

soundings farther off. It would shelter a large number of vessels. The

entrance is defended by the island of Paxaros [sic], on which, at

the proper season of the year, is found a prodigious quantity of eggs,

deposited by gulls, so that its surface becomes completely whitened by the

vestiges which they leave behind them. During the dry season, the hills

which surround the harbour present a sterile appearance, truly unpleasing

to the eye, and give but a bad idea of the prosperity of the town; while

the size of the houses, the number of its inhabitants, or the want of

cattle in its neighbourhood, do not tend to remove that impression. [...]

The founder of Guaymas is still an inhabitant of it; an old man, who is

seldom sober when he can get tipsy. He sometimes buys a barrel of liquor

to retail to the sailors of vessels who frequent the port. But, as he

says, he always likes to keep the tap running; so when there are no other

customers, he becomes one himself. [...] Guaymas is a miserable place,

that is, as far as regards the houses, covered with mould, so that, during

a hard rain, the inmates may take a shower-bath without going out of

doors. The rafters are whole palm-trees; and there is a large kind of

humble-bee which perforates them with the greatest ease, so that, by

degrees, these great bores, which serve the insect for a nest, so

weaken the rafters, that the lodger may sometimes find a grave without

going to the churchyard, the roof falling for want of due support; which

has since happened to the very house wherein we then resided."

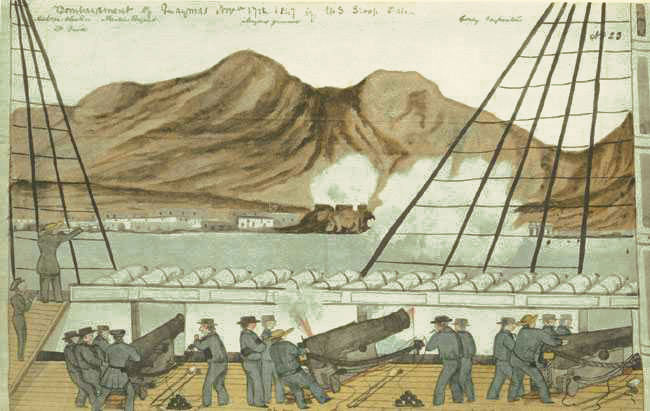

–A look at Guaymas from its harbor, under attack by the Yankees in 1847 in the Mexican-American War. Drawing by Gunner William H. Meyers, who indeed depicts himself, the rearmost figure in the darkest hat attending the gun at center. Acquired with others of Meyers' sketches by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and published in the rare 1939 book Naval Sketches of the War in California, a copy of which I happily own. The book has many images of interest to students of California history, and of the history of the Mexican-American War; but I limit myself to using on this site only three of Meyers' sketches in full, plus one detail from another. Here, we see the "sterile appearance" of the hills mentioned above by Hardy.

¶ 3.

–Richard

York: Richard York's correct name appears to be Richard

Yeoward. Yeoward was an agent of the British firm of William Duff & Co.

The ship co-owned by Yeoward (probably representing his employers Duff &

Co.) and Requena was the

Margarita.

–Commissioner-General

Riesgo: Juan Miguel Riesgo was the first governor of the

Estado de Occidente, the combination Mexican state which

comprised the former states of Sinaloa and Sonora, which were to be

separated again in 1830. I can offer a little more on Riesgo from the

same source quoted previously, R.W.H. Hardy's Travels in the Interior

of Mexico, p. 74ff: "The first person to whom I paid my respects on

my arrival here [Rosario], was Don Miguel Riesgo,

Commissary-general of the united provinces of Sonora and Sinaloa. [...]

I found him occupied in dictating dispatches to four clerks at the same

time, which he appeared to do with the greatest facility, even while

holding a conversation with me upon indifferent subjects. Whether he

owed this facility to memory or talent, it is difficult to determine, as

both these qualities may exist separately [...]. However, as he is the

most remarkable person in Rosario, I shall endeavour to give a

full-length portrait of him, observing only, that he sat to me but a few

times. Riesgo is a man whose jesuitically straight-combed hair and hard

features are considered, by those who know him best, to betray the

peculiar characteristics of his mind, The perpendicular furrows on his

face showed that the softening influence of a smile was a stranger

there, or, at least, that the experience was 'like Angels' visits, few,

and far between,' strongly indicating his habitual thoughtfulness and

cold calculation. The expression of his prominent eye showed quickness

of penetration, and, to a close observer, unsubdued irritability, and a

certain sinister and sycophantic disposition, which gave to his tout

ensemble the air of a courtier, joined to the sternness and pride of

a Republican in office. His firm tread was that of a man who knew that

his authority gave him importance, and had placed him in a situation to

make even his smallest wish obeyed by his inferiors. His whole carriage

indicated that he was neither ignorant of the great advantages of

possessing talents and education, nor careful to disguise the

supercilious contempt which he entertained for the greater part of those

by whom he was usually surrounded. Yet, with all the consciousness of

his own importance and mental superiority, there was a lurking

expression about Riesgo's mouth, which indicated the absence of entire

tranquillity, and gave rise to the suspicion of some hidden weakness in

his composition. [...] Certain it is, that although absent from his wife

and family, he was not condemned to forego the pleasures of female

society. But ever-waking scandal, we well know, seeks to fix upon the

noblest and most exalted, in order to level them with the common

standard of mankind; and may, therefore, have wantonly inflicted an

undeserved wound in the character of Don Miguel Riesgo. Whether or not

he sustained unmerited injury from such reports, he certainly suffered

much in the cause of the Revolution. At his own table we found him

hospitable, and exceedingly entertaining in his conversation, which

teemed with anecdote and severe satire, in the indiscriminate use of

which last he was by no means sparing, either to friend or foe. [...] In

his youth he had, I believe, been educated by the Jesuits, and, as I

understood, written a pamphlet in their justification. I would fain

attempt to relate some of his very curious stories; but it would be

impossible to retain the same spirit, and, above all, the same quaint

mode of expression." One can see why Requena could have felt

uncomfortable with Riesgo. Riesgo was born in Horcasitas; his

governorship of the Estado de Occidente lasted from September 12

to October 7, 1824; he died August 8, 1834.

¶ 5.

–The ship arrived at San

Pedro: Below, William Rich Hutton's depiction of the lonely

shore at San Pedro. One of the two structures shown is a warehouse/hide

house owned by Abel Stearns. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San

Marino, California. Call number HM 43214 (24). Used by permission.)

¶ 6.

–due to our taking the

wrong trail: "Roads in many parts of Mexico, and particularly

in the interior provinces, are merely paths traversed by horses and mules,

but never by a coach or waggon [sic]. And it requires a great

knowledge of travelling, constant observation, and nice discernment, to

make out the tracks which distinguish a high road from one which merely

leads to the open country, frequented only by those who go for wood; or

even from a rabbit track, as they all resemble each other as much as the

two blades of a pair of scissors" (from Hardy's Travels in the Interior

of Mexico, p. 224).

–arrived in Los Angeles towards the end of April: Ah, what is this unremarkable vale which strikes our eyes? Why, 'tis the site of L.A. in all its primitivity before undergoing the tender mercies of the human race. Observing from the east, well before Botello's time, we see where Los Angeles would be. The Los Angeles River, arriving from the San Fernando Valley at right, flows, if it flows at all, left towards the distant ocean. Careful observation at center will reveal what was to become La Loma de las Mariposas–Fort Hill–as well as the great Aliso tree which gave Aliso St. its name, and which was the focal point of the rancheria of Yang-Na, all the inhabitants of which appear to be away on a visit somewhere. The future Pound Cake Hill is visible, faintly, as is the range of hills someday to be known collectively as Bunker Hill; and Arroyo Seco is below us to our right. This view will impart a sense of the lie of the land for our proceedings.

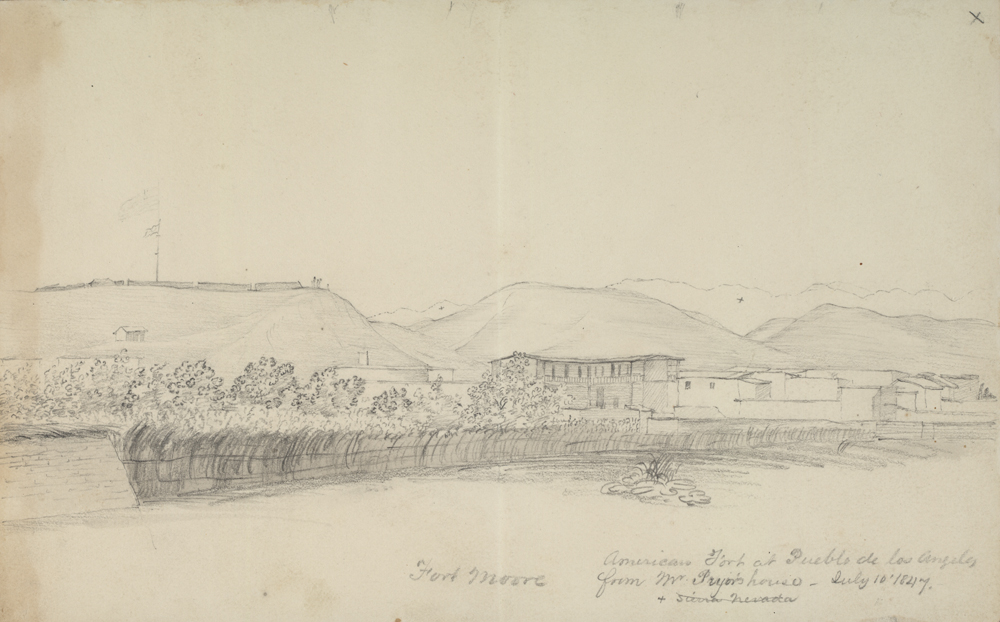

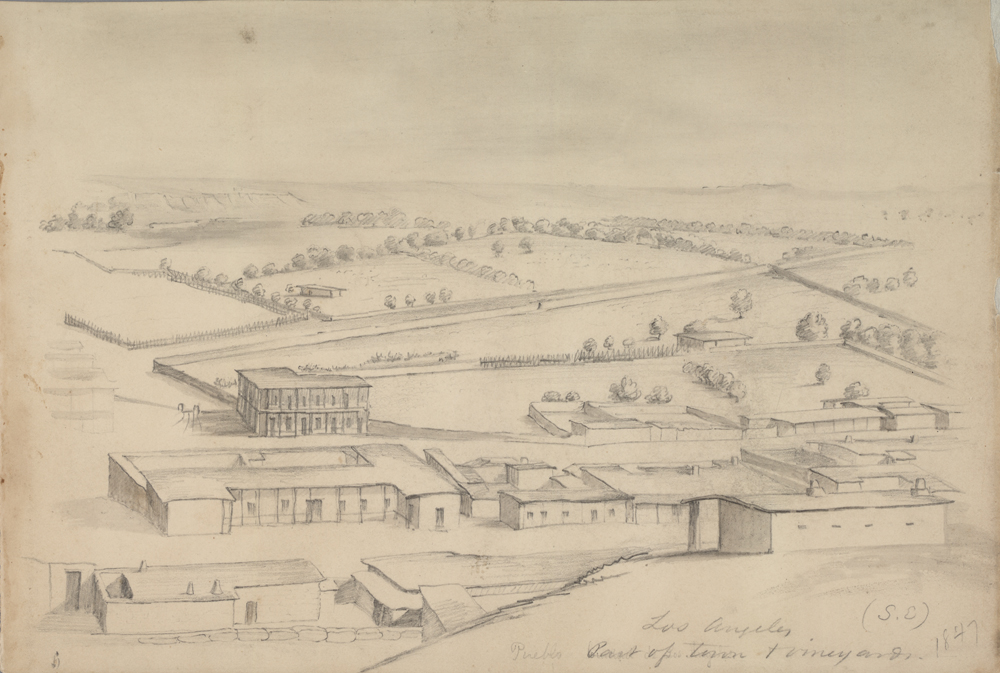

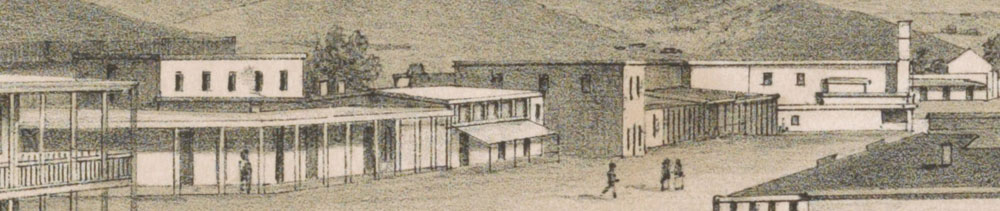

–Los Angeles: Botello and Johnson likely arrived in L.A. via one of two roads, amounting to either north or south of the Mesa. South of the Mesa would have brought them in on what came to be known as Aliso Street. From somewhat south of Aliso Street–to wit, from the roof of Nathaniel Pryor's adobe–William Rich Hutton gives us an idea of how something like this approach would have appeared in 1847, the main difference from the early 1830s being of course the presence of Fort Moore above the pueblo. At center as we approach, prominent is the two-story Bell Block. On the hillside below Fort Moore is the pueblo's old calaboose. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (25), used by permission.)

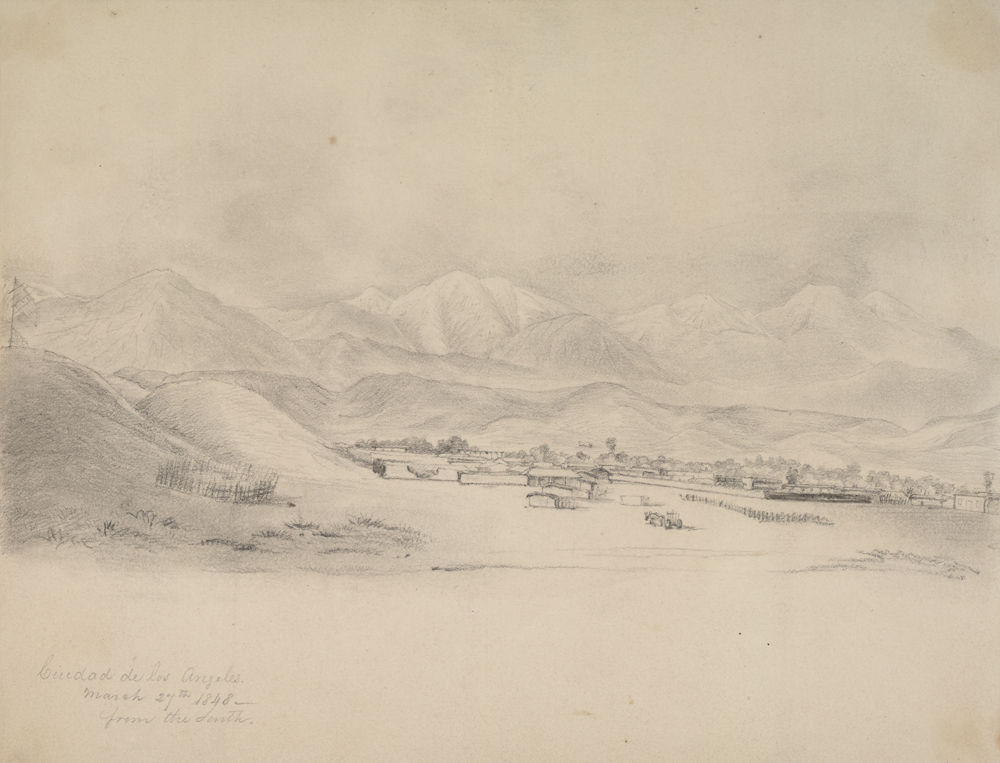

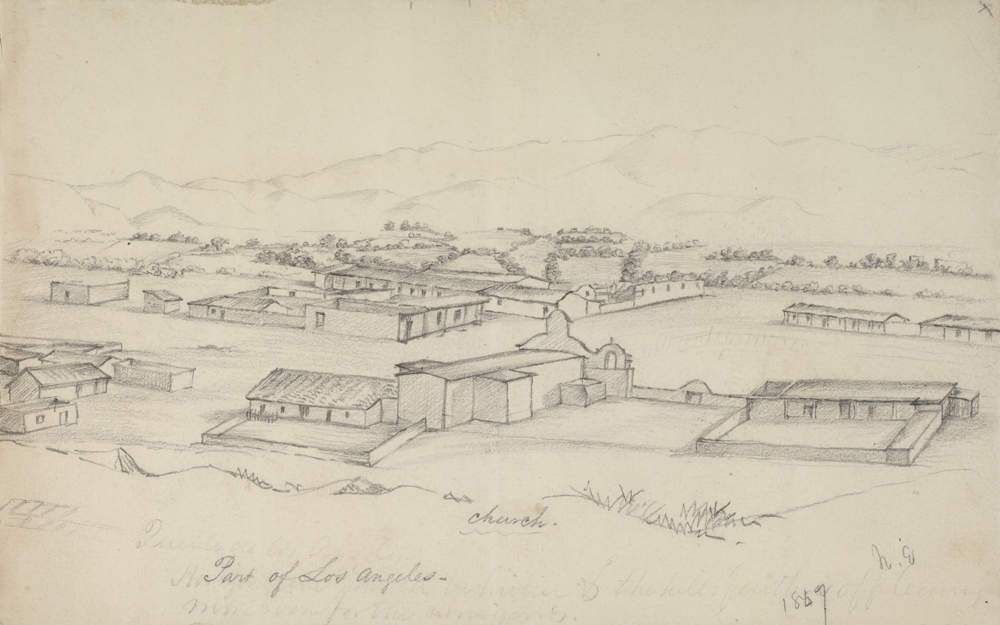

–But we must also see the Pueblo as we approach from the south. William Rich Hutton provides a drawing which I must admit baffles me in several ways; but we seem to be standing at about what would become 1st Street, a bit west of Spring Street, looking north. Hutton appears to have taken some liberties in this sketch, and perhaps we should take it as more of an "impression" than as a depiction. In particular, he seems to have suppressed any buildings south of what would now be Temple Street. This was likely a preliminary sketch for a more familiar color picture by Hutton, one which takes even more liberties but which compensates by featuring as amiable a horse as you could hope to see. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (28); used by permission.)

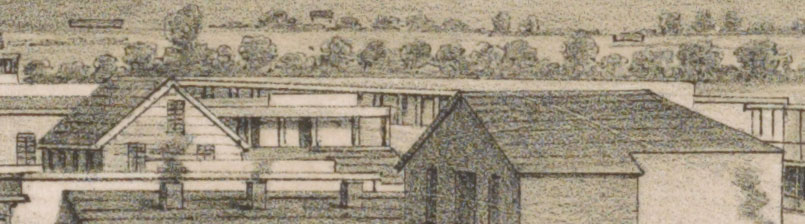

–Hutton also shares a very high view from the north, as L.A. appeared in 1852. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (32); used by permission.)

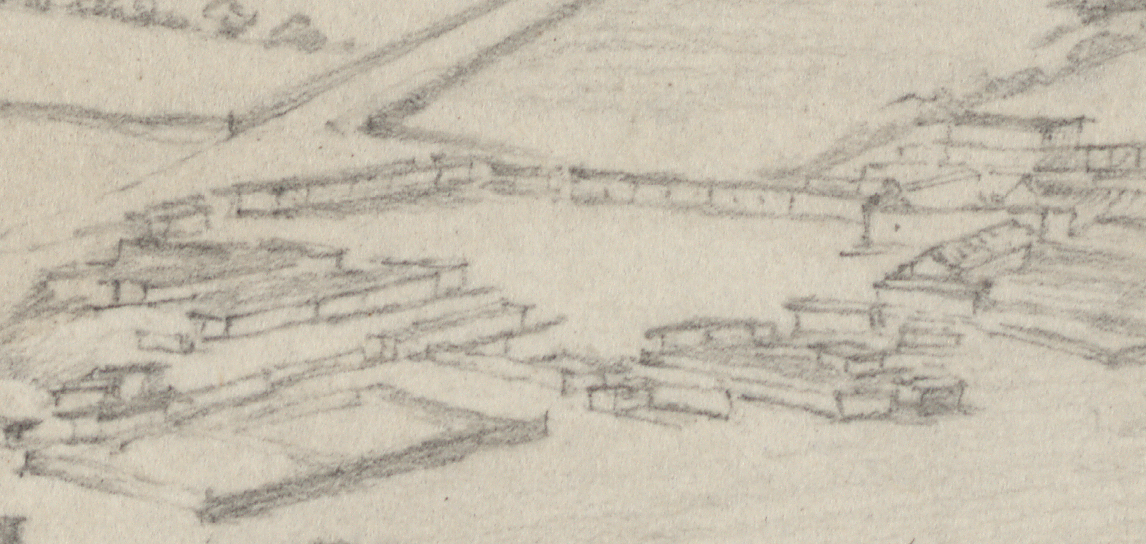

–Below, a much-enlarged detail from the above of the Plaza area in 1852. The Bell Block (near the upper right corner) and the Church (at the upper right corner of the Plaza) are easy to pick out. The Avila Adobe on what later would be Olvera Street is the building which edges closest to center left margin. Alameda Street exits the detail, going towards the south, at top center. (Permission from the Huntington Library as above.) The original Plaza, which evidently was still clear in Botello's first years in L.A. (1833-1834) now is the site of the several structures we see close to us at lower right.

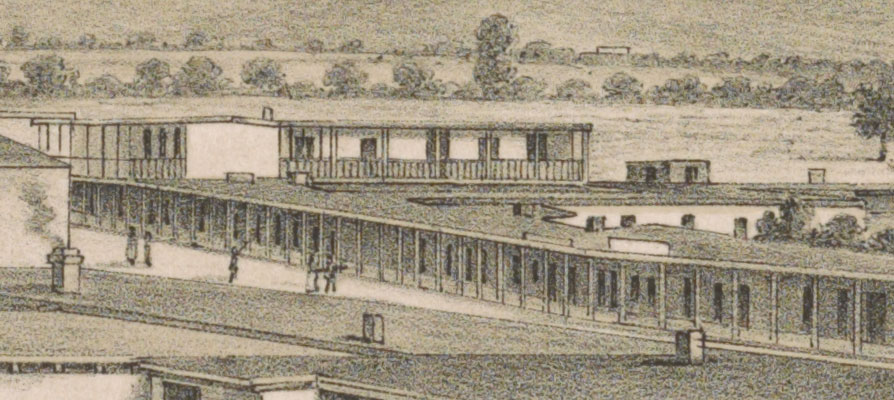

–South, east, north–now we need a look from the west, again courtesy of Hutton, who gives us in this and the next view probably the definitive views of our pueblo in the pre-Yankee era. Below us, at center, is the rear of the Plaza Church, the much-used rectory–so often a part of our story–is off to the left of the Church, with its own yard/corral. To the left of that, extending to the left edge of the picture, is the site of the original Plaza, still partially clear. The Plaza corner of what would become Olvera Street is beyond the top of the Church's facade, with Olvera Street extending to the left; on it, we get a good view of the front of the Avila adobe. Across the Plaza, opposite the church, we see the Lugo adobe, not yet a two-story structure. In front of us, next to the Church, is a yard which might or might not be a cemetery; to the right of that is the Mariano Dominguez adobe. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (29). Used by permission.)

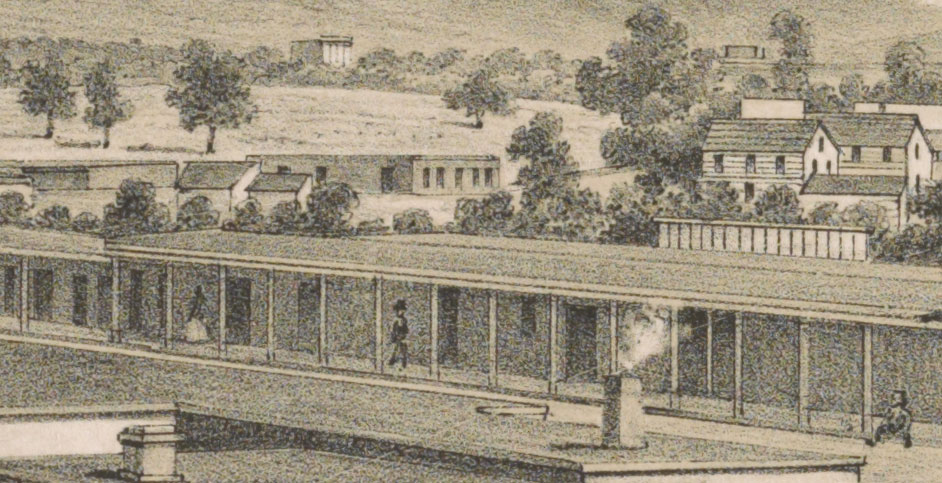

–For unknown reasons, Hutton skipped over the interesting area from the south perimeter of the Plaza to Aliso Street, depriving us of a view of the Jose Antonio Ezequiel Carrillo home, the two-story Vicente Sanchez home, the back of the Coronel adobe, and the other features of that area. But, in the view below, we can see from the west what we saw, a few images above, from the east: the two-story Bell Block at what would be the corner of Aliso Street with Los Angeles Street, and, beyond it, the Nathaniel Pryor adobe, from the roof of which Hutton drew the earlier image. On the nearer side of the Bell Block is El Palacio, the Abel Stearns residence, which features so prominently in L.A. history; we shall get a look at Don Abel himself in a moment. Going to the right, along Main Street, passing one lot of a jumble of small structures, we come to the Isaac Williams adobe with its large corral in back. The Williams adobe would be used for governmental purposes for a time, in both the Mexican and Yankee eras (it was the court house for the famous Lugo case), before becoming the original Bella Union Hotel. To the right of the Williams adobe, and, like it, partially obscured by the old calaboose so near us on the right, is the building which enters into Botello's story as Gaspar Oreña's shop which one night developed a hole in one wall. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (30). Used by permission.)

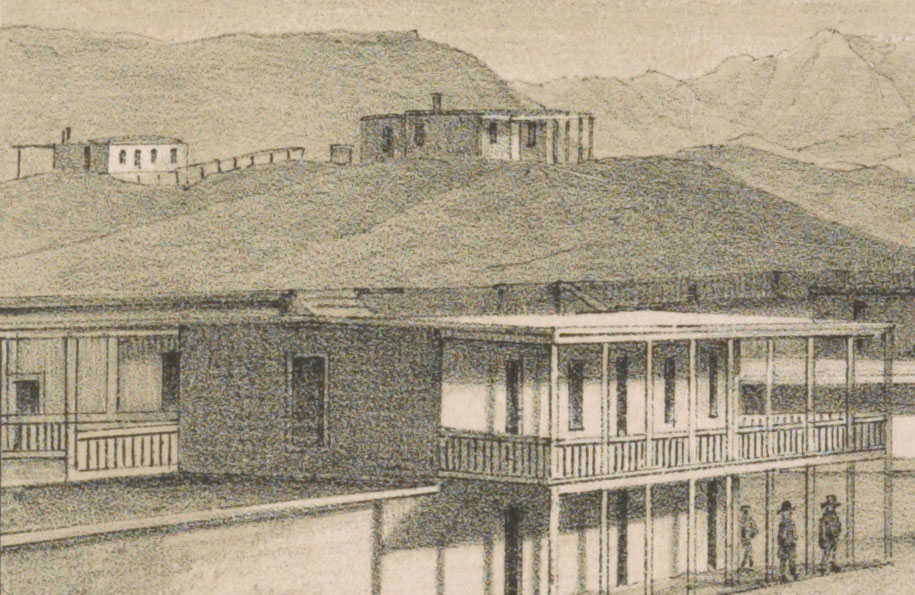

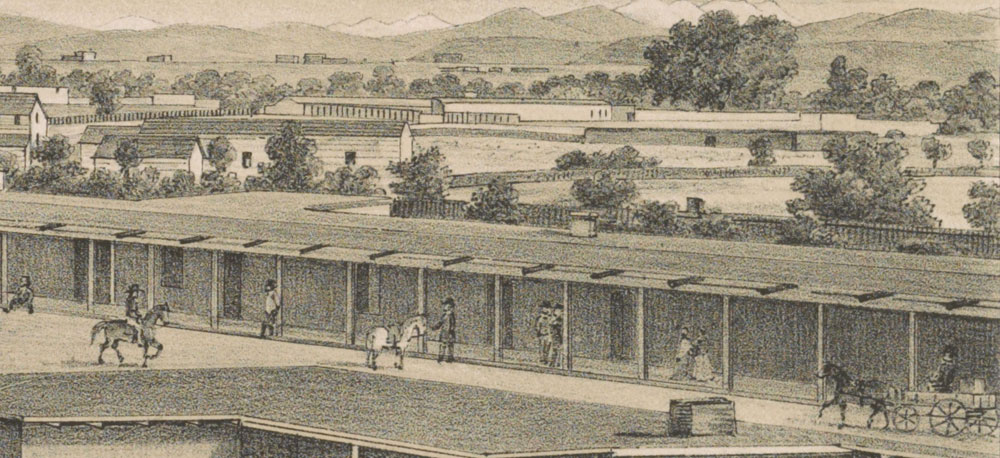

–Let's knock about town a little more, courtesy details from Kuchel & Dresel's 1857 view of L.A. Though in 1857 Los Angeles had fewer adobe structures and more frame buildings, we can still get much of the feel of how the cityscape had been a mere decade before. In the following series, our standpoint is a rooftop at about Main and 1st Streets. First, we look up and to the left, where the old calaboose presides in its minatory way over town. Above and beyond it can be seen, with some careful scrutiny, a bit of what remained of the defenses surrounding Fort Moore. Immediately before us is the "new" Temple Block at the junction of Spring, Main, and what would become Temple Streets.

–Lowering our gaze to look down at the street, we again see the "new" Temple Block (the "old" Temple Block is beyond it, and extending to the right), and now see, below us, the roof of the original structure of the U.S. Hotel, which hotel persisted, rebuilt, well into the 20th Century).

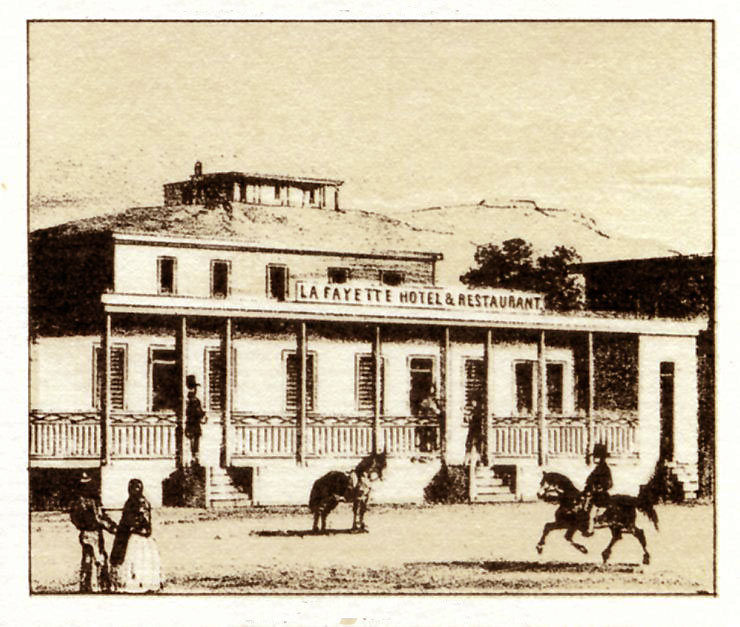

–The west side of Main St. between the Temple Blocks and the Plaza Church is not often depicted. The long building to the left is the old Temple Block, which would eventually become the Downey Block. Continuing to the right, this would have been the location of the De Celis and Salazar properties in Botello's time; later, the Lafayette Hotel would be found here. The building in the lower right corner, of which we see just the roof, will feature in Botello's narrative as the location of Arnaz's store; just beyond, next door to it, of which we can see almost nothing, is the building which was originally Isaac William's adobe, then (often) the "Government House" in the Mexican era, and finally the Bella Union Hotel. Further beyond, we see the bell tower and south wall of the Plaza church; and, beyond that, the building which was probably the site of the murder of Mr. Fink, detailed by Botello in the last paragraphs of his work.

–Now we come to the most interesting Plaza area. At left is, as we saw above, the Plaza Church etc. To the right, across Main St., is the Segura adobe. Continuing to the right, we come to what would eventually be Olvera St. The artist does not depict in this direction anything beyond the row of buildings immediately north of the Plaza; otherwise we would get a sidelong view of the Avila Adobe on Olvera St. On the right-hand side of that street, we see the adobe which was originally that of Tiburcio Tapia and later that of Agustin Olvera. The two-story structure which appears to be immediately to the right of the Tapia adobe is actually on the near (south) side of the Plaza, and is the home of Vicente Sanchez. To the right of that, we see the side of the Lugo adobe on the east edge of the Plaza. Alas, we can't see anything of the Plaza itself.

–Continuing to the right from the above (near top left, we see just a bit of the corner of the Lugo adobe), the central feature in this view is the long colonnade of posts running along the east face of the Calle de los Negros, a full view of which is blocked by Coronel's adobe at Coronel Corner. Beyond, we see open fields, which likely were actually vineyards. L.A. was to some degree surrounded by vineyards; the sweet smell of the vine flowers, and then of the ripening grapes, would combine with the aroma of the native chaparral to give L.A. a delightful air.

–And so we return to the Bell Block, from yet another angle. This colonnade of posts marks the east face of Los Angeles Street. Again we see the fields beyond, which were largely vineyards.

–Los Angeles Street continues to "drag its slow length along." The frame houses seen in the background would not have been there during the era of Botello's narrative. The gentleman sitting on the boardwalk at lower right is resting from our tour of the town; but I promise him and you that this little survey is nearly done.

–The gentleman does not believe me!–and so keeps his seat at mid-left. But we continue south on Los Angeles Street. We might pause, however, to gaze at the great old Aliso tree at upper right, the namesake of today's Aliso St., and, long ago, the gathering-place for the native Americans of Yang-na.

–And so we have circled back to the immediate environs of Main Street and First, where a hospitable family is gathering in their backyard to refresh us with their delightful conversation and–I hope–some cool drinks.

¶ 8.

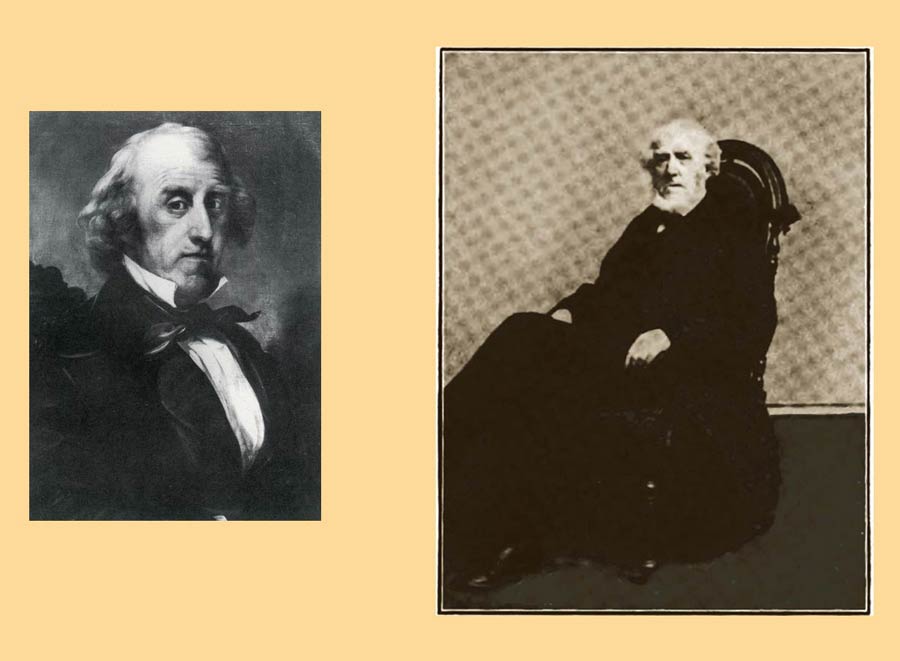

–Mr. Abel

Stearns: And now for the owner of the previously-mentioned

El Palacio: Below, Abel Stearns in middle age and in old age.

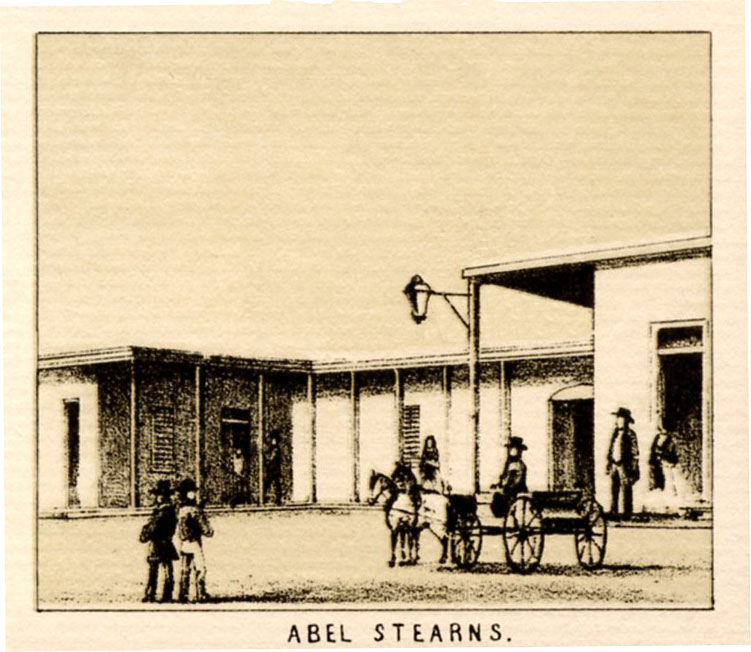

–the house of Mr. Abel Stearns: Which is to say El Palacio, below, as it appeared in 1857 (I think the lamp is the only innovation).

¶ 10.

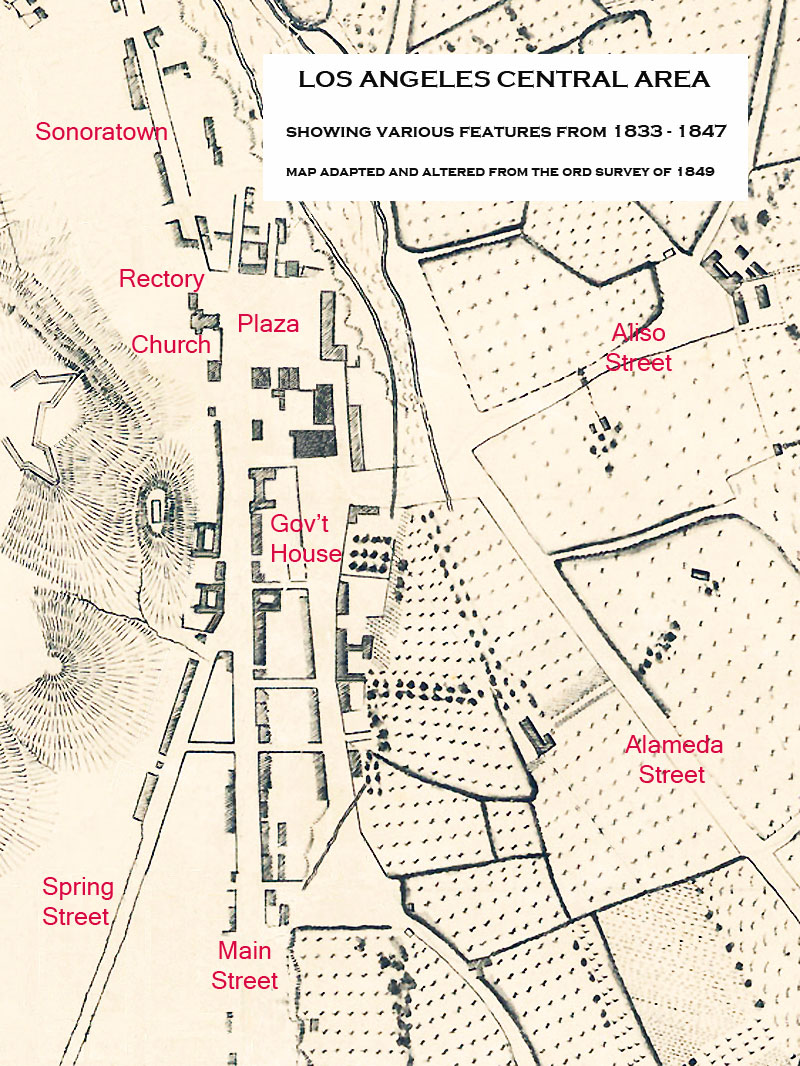

–A simplified map of

central Los Angeles giving an idea of the area ca. 1833-1847,

with features from various years (for instance, the Fort was not there

until the end of the period). Stearns' El Palacio is the structure

immediately north of Government House. Government House was, earlier,

Isaac Williams' adobe, and, later, the Bella Union Hotel. The Jail is the

rectangle at the top of the hill to the left of Government House (and, on

the map, below and to the right of the Fort). Observe the slopes of the

hills and ponder well the direction of the water runoff during and after a

rain. The old plaza–the one which preceded the one on the

map–was located at the site which is under the word "Rectory" on the

map; one can see how the water runoff from the adjacent wide slope of

Loma de las Mariposas (Fort Hill) would have been directed largely

at the site of the old Plaza, the flooding which prompted the change of

plaza location.

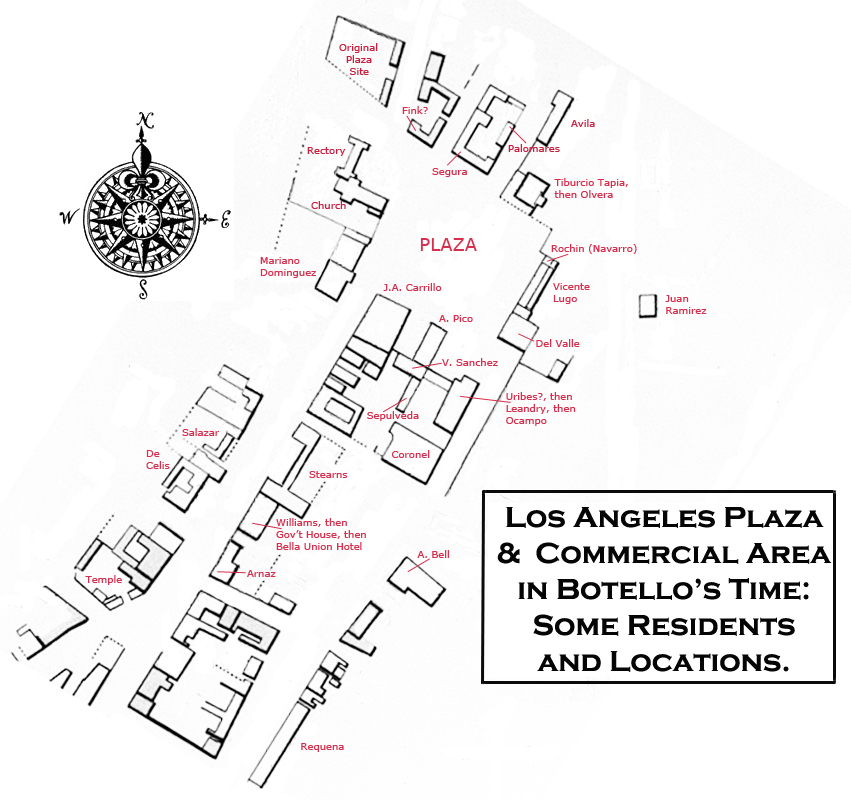

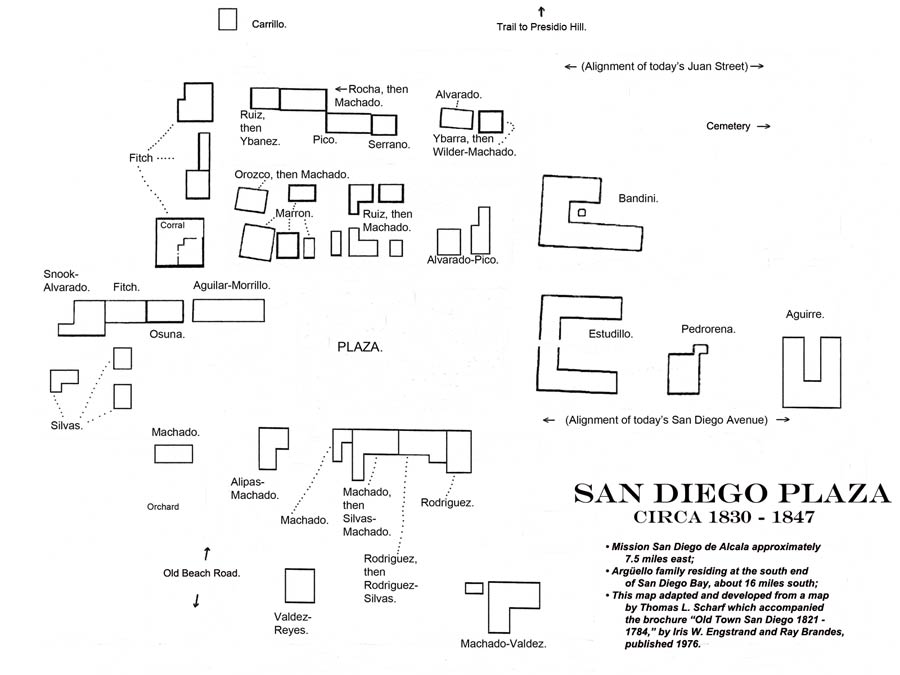

–A map (below) of the plaza and commercial area of 1833-1847 Los Angeles, indicating some sites and residents pertaining to our tale.

¶ 16.

–Day was arrested, taken

to prison, put in a cell, and shackled: In a view from 1857,

we see (behind and above the later Lafayette Hotel) Day's prison, L.A.'s

venerable calaboose. The old jail was later turned into a residence in

which the future Mayor Eaton was born.

¶ 17.

–"was left vacant and

remained" would probably be better rendered "be left vacant and

remain".

¶ 19.

–Don Tiburcio

Tapia: Some more on Don Tiburcio: 1829, "We stopped at the

house of Don Tiburcio Tapia, the 'Alcalde Constitucional' of the town,

once a soldier in very moderate circumstances, but who by honest and

industrious labor had amassed so much of this world's goods, as to make

him one of the wealthiest inhabitants of the place. His strict integrity

gave him credit to any amount, so that he was the principal merchant, and

the only native one in El Pueblo de los Angeles" [Alfred Robinson, Life

in California, p. 63].

–"The insisted"

should be "They insisted".

¶ 20.

–Brigadier-General Don

Jose Figueroa: A little information has come to hand about

Figueroa's career prior to his arrival in California. In the latter part

of 1811, then-Colonel Figueroa, under Morelos and Trujano, was spreading

the revolutionary insurgency to Tehuacan, in the state of Puebla, Tehuacan

being "the commercial centre of the provinces of Puebla, Oajaca, and Vera

Cruz" (History of Mexico 1804-1824, by H.H. Bancroft, p. 398).

February, 1821, finds him being sent by Iturbide on a mission to negotiate

with Guerrero (op. cit., p. 708). August 9, 1824, as President of

the Congress of the State of Mexico, he was a signatory to a provisional

organic law (History of Mexico 1824-1861, by H.H. Bancroft, p. 22).

In Fall, 1825, he was leading three hundred or so men in a campaign

against the Yaqui Indians in the area around Tubac, Tucson, and the Gila

River (see the site Tubac Through Four Centuries, by Henry F.

Dobyns); by August 31, 1826, he was comandante at Arizpe in

northern Sonora (see The Taos Trappers, by David J. Weber, p. 114).

Referring to about the same time, Hardy (Travels, p. 126) writes,

"In the neighborhood of Babiacora [Baviacora, Sonora], General

Figueroa is working a silver mine which formerly produced a great deal of

metal; but the Commandant General has not yet found it very productive,

besides an expensive outlay." Further biographical information may be

found in Bancroft History of California 3:234 (footnote), where ,

in the main text, Bancroft makes the comment "it is believed that his

appointment [as governor of California] was a measure dictated less

by a consideration of his interests or those of California than by a

desire to get rid of a troublesome foe."

¶ 26.

–green

spectacles: "The road from hence to the port [Guaymas]

is very sandy, and the reflection of the sun from the sandy soil is very

distressing to the eyes. Indeed this observation applies to all the roads

in the republic whereon I travelled in my various migrations, which were

neither few nor short. Strangers to the country use coloured spectacles,

which in some degree obviate the inconvenience" (Hardy, Travels in the

Interior of Mexico, p. 226).

¶ 27.

–his wife, Maria del

Rosario Villa–la Chala: Who might have looked like this,

La Chiera, from the 1855 Mexicanos Pintados por si

Mismos. Note the cigarette.

¶ 28.

–Gervacio [Alipas] [...]

was employed as a cowboy: And might have looked like

this, Claudio Linati's depiction of a Mexican caballero.

¶ 28-29.

–General

remarks: Many of these details could only have come from

Alipas and/or la Chala, presumably in statements made while in

custody and in response to the inevitable question, "What happened?".

¶ 29.

–his legs remained

uncovered: Something that happened during the burial, or

some consideration, made Alipas and la Chala leave prematurely.

Perhaps they saw or heard the wood-collector about to be mentioned

approaching in the distance.

¶ 30.

–the skillful Antonio

Ignacio Avila: Jose Antonio Ygnacio Avila, usually known as

Antonio Ygnacio; ca. 1776-1783, born at Villa del Fuerte, Mexico; parents,

Cornelio Avila and Maria Ysabel Urquidez; by 1783, present in California

with his parents; by 1799, present in L.A., when given land; February 6,

1803, married Rosa Maria Ruiz at Santa Barbara presidio; 1804, resident in

L.A.; 1810-1811, soldier in L.A. militia; February, 1816, present in L.A.,

evidently living at Rancho San Pedro; August, 1816, as a member of the

L.A. militia, serving at San Diego presidio; 1818, involved at Santa

Barbara and San Juan Capistrano in the defenses against oncoming pirate

Bouchard; 1820, 1821, regidor in L.A.; ca. 1821, present in L.A. with wife

and seven children; the "tract called Sauzal Redondo was temporarily

granted by the commandant of Santa Barbara in 1822 to Antonio Ygnacio

Avila, the land apparently belonging to the pueblo" (regranted 1837);

1823, present in L.A. in the militia; 1823, on church compliance list in

L.A.; evidently the Antonio Ygnacio Avila (Abila) mentioned in the 1824

will of Jose Bartolome Tapia concerning a transaction of 1823 involving

Antonio Briones (Priones); 1835-1848, juez de campo most of the

time, "and always prominent in the pursuit of Ind. horse thieves," quoth

Bancroft; 1836, present in L.A. as a ranchero; 1836-1837, of the

anti-Alvarado faction; January 15, 1837, Osio borrowing "one of Don

Antonio Ignacio Avila's very fine horses, which he called

gutierreños"; May 14, 1838, going to visit Pio Pico who was

imprisoned at the Home of Jose Antonio Ezequiel Carrillo; December, 1839,

evidently in prison, or having been in prison, as Joaquin Ruiz was tried

then for attempting to release him; 1842, juez de campo. 1842,

contributing towards the cost of provender for Michelorena's

batallon; 1844, present in L.A. as a laborer and landowner; 1845,

1848, juez de campo; 1850, present in what was to become east

Orange County as a grazier; September 25, 1858, died; September 26, 1858,

obsequies at Plaza church; October 2, 1858, published (Los Angeles

Star): "Died, on Saturday last, the 25th ultimo, in this city, at the

residence of Don Ygnacio Del Valle, Don Antonio Ygnacio Abila. His age was

not known, but he is supposed to have been over ninety years old. He was

born in the Villa del Fuerte, Mexico, and came very young to California;

served his country as a soldier, and by industry and integrity accumulated

great wealth, the greater part of which he gave away in works of charity.

In him the poor always found a sympathizing friend and protector. His

remains were escorted to their last resting place on Tuesday morning, by a

large concourse of citizens. The funeral services were performed in the

church by Rev. Father Raho and the other clergymen of the city. The direct

descendants of deceased number over one hundred and twelve"; children:

Maria, Maria Francisca de Paula, Maria de la Asuncion, Josefa, Juan, Jose

Martin, Maria Rafaela, Maria Ascencion, Pedro, Maria Marta, Dionisio de

Pilar, Higenio; illegitimate child with Maria Gregoria Matilde Cota: Maria

Antonia (last name also seen as Rendon); illegitimate child with Josefa

Castro: Jose del Carmel; son Juan Avila, dictating to Bancroft's worker

Thomas Savage within days of Savage's recording of Botello's material,

discusses his father, from which here is an extract (translation by

Alfonso Yorba, published in the 1939 Orange County History Series No.

3, p. 1): "My father was juez de campo from early manhood, in

the jurisdiction of Los Angeles, until his advanced age no longer

permitted him to mount a horse. Many times he asked to be relieved,

particularly in his last years, but the people insisted that he remain in

office, and there was no other remedy than for him to do as they asked. On

almost every occasion in which the people of Los Angeles had to send

expeditions, be it against thieves or against insurgents, deserters, or

criminals, he went at the head, because he was not only a man of great

activity and energy, but also because he was a good tracker, a faculty

which he did not lose up to the last moment of his life." Almost

undoubtedly, Duhaut-Cilly, writing of ca. April, 1827, refers to Avila in

this passage from his A Voyage to California..., referring to three

criminal Indians whom he had been entrusted to convey to San Diego:

"[While Duhaut-Cilly was anchored at San Pedro,] they were clever

enough to steal the only boat lying alongside the ship and, after first

letting themselves drift noiselessly away, they disappeared without being

noticed by the two seamen of the watch. As soon as I was informed of the

matter I sent two boats in search of the one they had taken, and it was

found abandoned on the rocks of Point San Vicente but without damage.

[...] I learned later that after wandering for several months in these

deserted hills they had finally been recaptured by a ranchero of the

neighborhood [note the reference above to Avila's tract of "Sauzal

Redondo"], well known for exploits of this kind. He made the poor

Indians pay dearly for the several cows they had killed for food; catching

them by surprise one day, he succeeded in garroting two of them

[doubtlessly via lassoing them] and put a bullet between the

shoulders of the third, who was fleeing" (Duhaut-Cilly, A Voyage to

California, translated and edited by August Frugé and Neal

Harlow, 1997, 1999, p. 92). So we understand all the better Botello's

reference to "the skillful Antonio Ignacio

Avila."

–doubtlessly by lassoing them in the above footnote about Avila: "This noose or lasso, used in all the Spanish possessions of the two Americas, is a leather rope as big around as the little finger and fifteen to twenty fathoms in length [75 to 120 feet]. While one end is fixed firmly to the saddle-bow, the other is tied in a running knot. For anyone other than these skillful riders such a weapon would be quite useless; in their hands it is a powerful and formidable arm. With it they have been known to confront the lances and bayonets of regular troops. [...] When a man wishes to use the lasso against an animal or another man, he holds it coiled in one hand while he gallops within fifteen feet of the enemy, whirling the lethal loop over his head like a sling. And at just the right moment he casts it with such skill that he never fails to bind the neck or the body or the legs of the one he wants to catch, and whom he drags cruelly along the ground as his horse gallops on" (Duhaut-Cilly, op. cit., pp. 69-70).

–gutierreños in the above footnote about Avila is uncertain in its signification. It's possible that Avila somehow came by the horses through Lt. Colonel (and sometime governor) Nicolas Gutierrez, commanding the soldiers based at Mission San Gabriel.

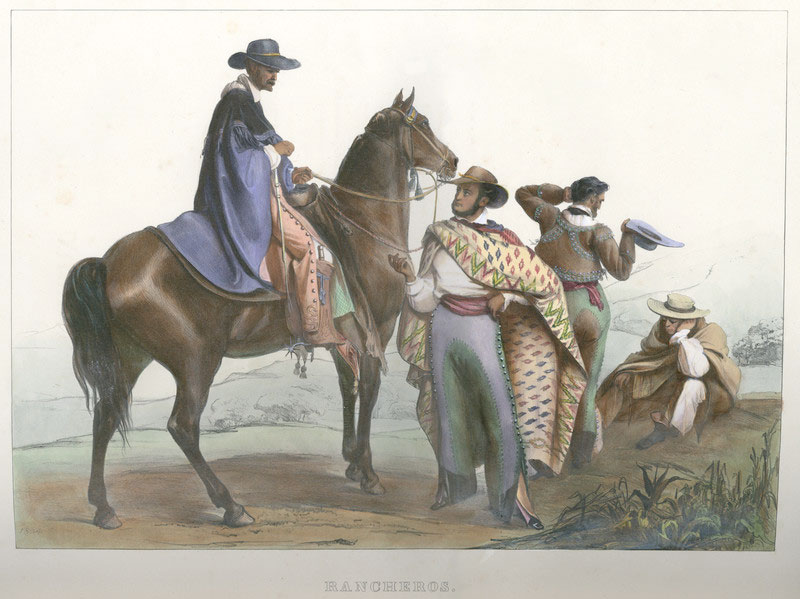

–as a ranchero (in the note above about "the skillful Antonio Ignacio Avila"): An image by Carl Nebel of Rancheros, from 1836 (below).

¶ 31.

–All of this caused an

uproar in town. [...] Everyone was crying bitterly: Aside

from political shenanigans, crime per se was extremely uncommon in

California at this time. A murder was profoundly shocking to society in

general: "From 1819 to 1846, that is to say during the entire period of

Mexican domination under the republic, there were but six murders among

the whites in California. As in the golden reign of England's good King

Alfred, a log cabin could hold all the criminals in the country. There

were then no jails, no juries, no sheriffs, law processes, or courts;

conscience and public opinion were law, and justice held an evenly

balanced scale" (from Bancroft's Popular Tribunals, Vol. I, 1887,

p. 62). In this specific case, "Horror and indignation took possession of

all minds, and while for the murdered man the mercy of God was

implored, exemplary punishment for the murderers was debated. [...]

Some were desirous that the criminals should be immediately executed;

but their ardor was restrained by the greater prudence of others, who

reminded them that such proceedings could only be excused on the

ground of necessity, and when carried out with coolness and in

accordance with the rules and principles of strict justice. The wisdom

of these suggestions was acknowledged, and the threatened outbreak

checked. On the 30th the funeral of Feliz took place, and the occasion

gave rise to a renewal of the popular clamor. Nothing but the

assassination was talked of, and the sentiment was fully approved that

an example was necessary to prevent the possible occurrence of similar

crimes. But holy week was at hand, and it was thought it would be

tantamount to sacrilege were the blood of so foul an assassin to stain

the remembrance of that most solemn of tragedies. Therefore the first

work-day after Easter, which would be the 6th of April, was fixed on

as that of the execution. A heavy storm which raged during the whole

of that day made postponement necessary, but on the 7th, at an early

hour, the most respectable men of all classes of the community

assembled at the house of John Temple. A Junta Defensora de la

Seguridad Publica, or Board of Public Security, was organized.

Victor Prudon, by birth a Frenchman, but a naturalized citizen of

Mexico, was chosen president. Manuel Arzaga, ex-secretary of the town

council, was elected secretary, and a retired officer of the army,

Francisco Araujo by name, appointed military commandant. [...] It was

then determined that both the man and the woman should be shot. The

junta was declared to be in permanent session until such time as the

object which called it into being should be accomplished, and measures

to that end were after discussion unanimously concurred in. At two

o'clock a sub-committee, with a copy of the resolutions, waited on the

alcalde, who thereupon convened the town council. At three o'clock, no

communication having been received from the alcalde, a message was

sent by the junta to that official, notifying him that the time

allowed for his action had elapsed, and informing him that the

resolutions of the junta were about to be carried into effect. No

answer was returned; but the second alcalde, accompanied by the

treasurer and another member of the council, appeared before the

junta and desired to be informed if that body recognized the legally

constituted authorities, and if so, what might be the significance of

this illegal assembly of armed men. The former question was answered

in the affirmative, and the answer to the latter, the magistrate was

informed, was contained in the resolutions which had been sent to the

first alcalde. At half-past three, by order of the junta, peaceable

possession of the guard-room of the jail was taken. No answer had yet

been received from the first alcalde, although he had sent a member of

the council to invite the president of the junta to a conference, to

which request answer was made to the effect that, apart from the

junta, the president was not at liberty to enter into negotiations. At

four o'clock both alcaldes made their appearance before the junta; a

resolution of the council condemnatory of the proposed illegal action

was read, and an attempt made to dissuade the junta from its purpose.

Convinced that their efforts were useless, the authorities withdrew,

after enjoining on those present the preservation of order, and

receiving the assurance that all measures necessary to that end had

been taken. [...] The military commandant was more compliant than the

alcaldes; he caused arms to be given to the firing party, and gave

orders necessary to the occasion. At half-past four the president of

the junta ordered Alipas to be brought forth for execution. Already

his irons had been filed so deeply that a single blow of the hammer

released his hands. The man was then shot, and after him the woman"

(op. cit., pp. 63-66).

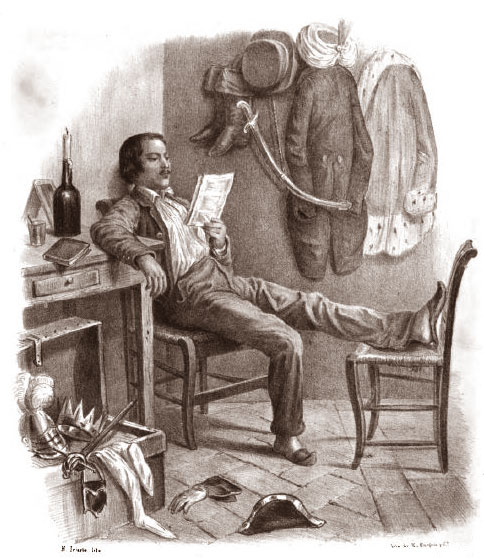

¶ 41.

–formed a governmental

plan: This image, the 1855 Mexicanos Pintados por si

Mismos's El Cómico de la Legua studying his script, could

just as easily serve as an illustration of one of the era's

políticos preparing his latest manifestación.

¶ 54.

–Bandini [...] went with

a few men to Sepulveda's house in order to arrest him: Below,

Don Jose hospitably awaits visitors on his doorstep. Image from 1857.

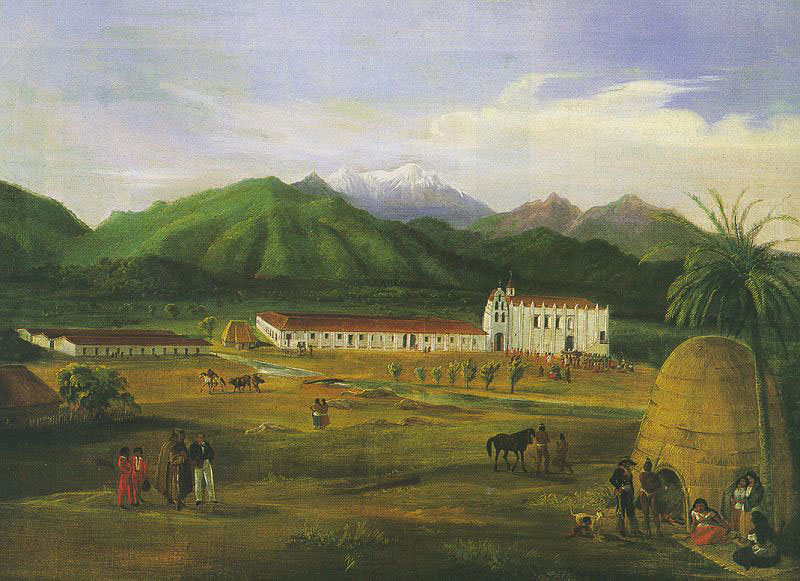

¶ 60.

–in command at San

Gabriel: Naturalist Ferdinand Deppe's 1832 oil of Mission San

Gabriel and its surroundings, below. The painting is now in the

collection of the Laguna Art Museum.

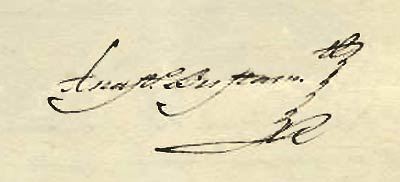

¶ 73.

–where was the rubric of

the President of the Republic?: Here it is (below), the

signature and rubric of Anastasio Bustamante.

¶ 79.

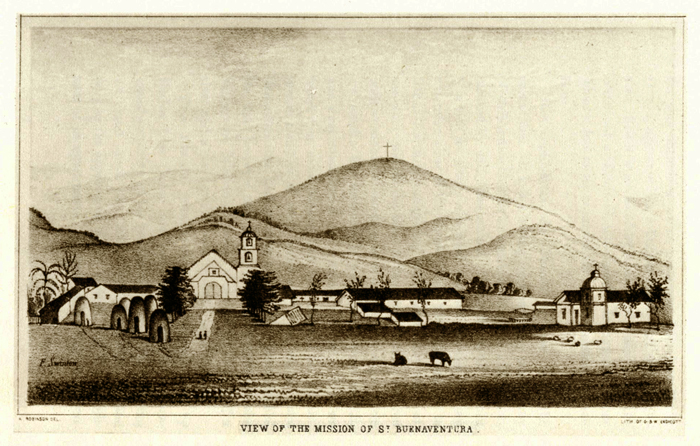

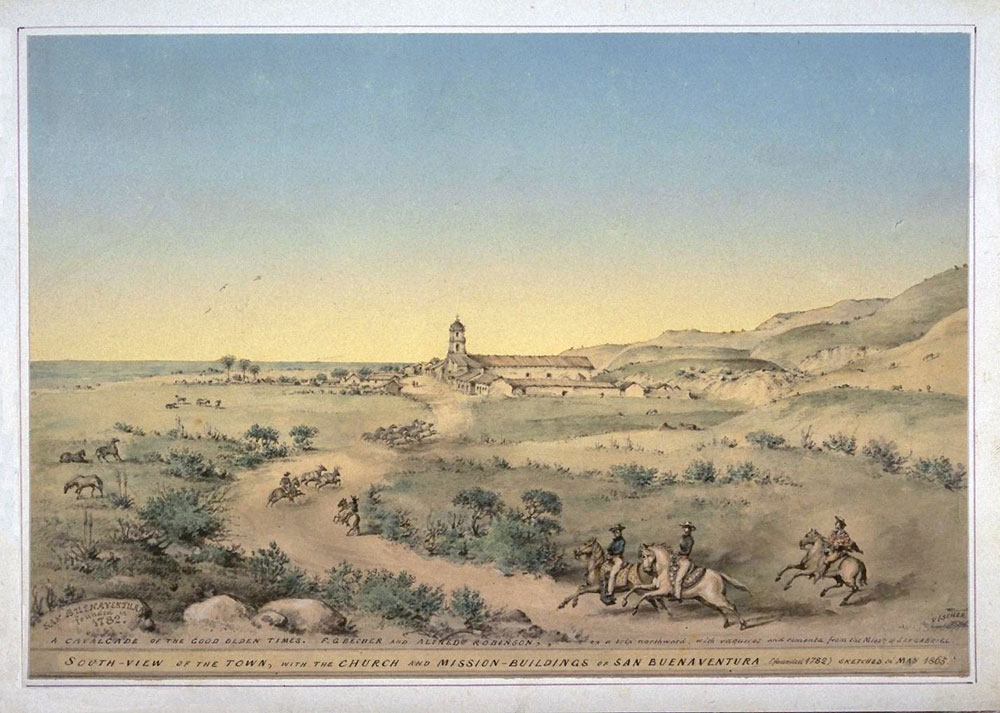

–we

withdrew to San Buenaventura: Below, from

Alfred Robinson's Life in California, San

Buenaventura.

–San Buenaventura: Another angle on San Buenaventura, this time as it would appear to those arriving from the south, courtesy Edward Vischer.

–the mission road was impassible by foot: "The morning after, we set out on an excursion to St. Buenaventura. The road thither is partly over the hard sandy beach, and at times, when the tide is low, it is possible to perform the whole journey [between Santa Barbara and San Buenaventura] over this smooth level. We were not over two hours on the road" [p. 49, Alfred Robinson's Life in California]. Also, impassible should be impassable.

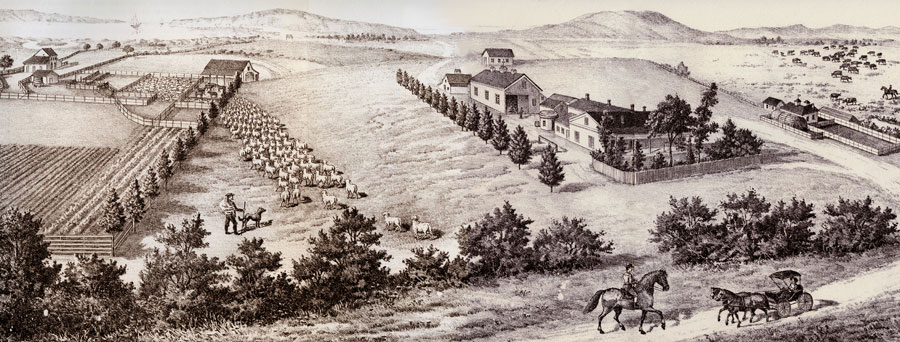

¶ 80.

–something to be taken

care of at his Rancho Los Alamitos: Below, Rancho Los

Alamitos several decades later in its years of ownership by the Bixby

family. We look west towards Palos Verdes. The clump of trees near the

middle in the distance is probably the neighboring Rancho Los

Cerritos. The land mass at upper left corner is part of Catalina. The

"mountain" in the distance at mid-right would be Signal Hill.

¶ 82.

–Ayala: Due to

mention of Ayala in the memoirs of Victoriano Vega, it is now certain

that this Ayala is Juan Pablo de los Santos Ayala, information on whom

can be found in the Botello book's notes to ¶ 134.

¶ 85.

–it was Don Juan

Avila: Avila himself recalls this in his Notas

Californias dictation for Bancroft: "When it was known in Los Angeles

that our force [at San Buenaventura] was threatened by the enemy, Governor

Carrillo asked for reinforcements and about twenty of us set out under the

command of Don Pio Pico. We got as far as the Santa Clara River where we

came upon some fugitives on foot who gave us news of our forces having

surrendered."

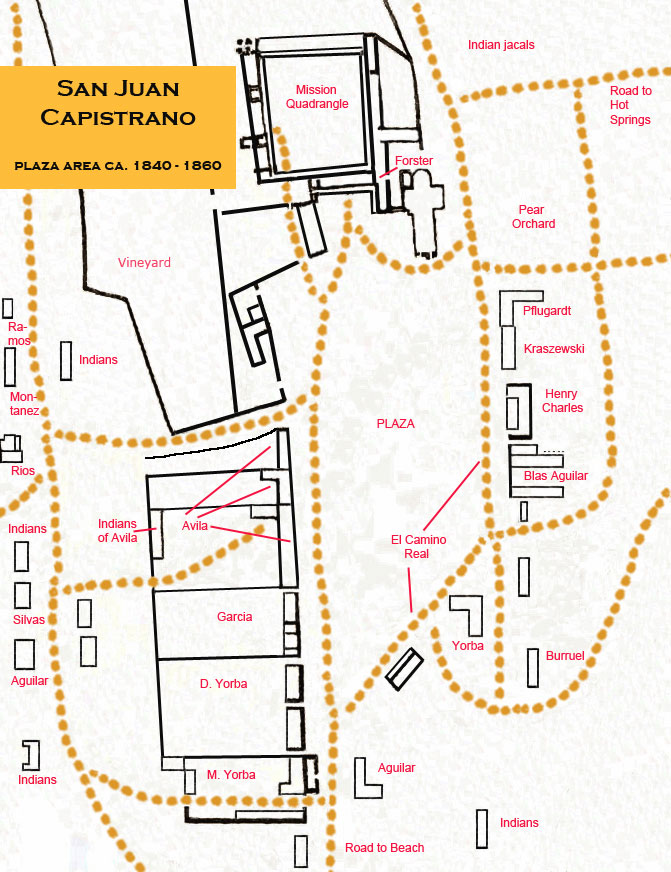

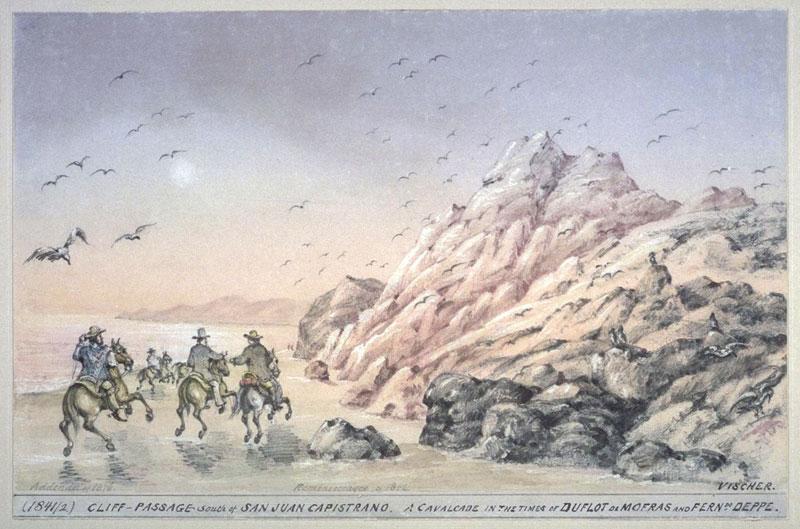

¶ 91.

–I reached San Juan

Capistrano: Below, a map of the San Juan Capistrano plaza

area, much simplified, showing various features selected from the era

1840-1860. I have made an effort to include some details which

particularly relate to something which will be of interest to many

historians, namely the locations of those involved in the January, 1857,

incursion of the Juan Flores/Pancho Daniel gang. The highly attractive

lines of buff-brown blobs indicate roads and paths. The road to the Hot

Springs is also the road to the Temecula area, Mission San Luis Rey, and

San Diego. The usual Los Angeles road would be what exits this map at the

top, which proceeds in that direction through the various Santa Ana

ranchos and so on.

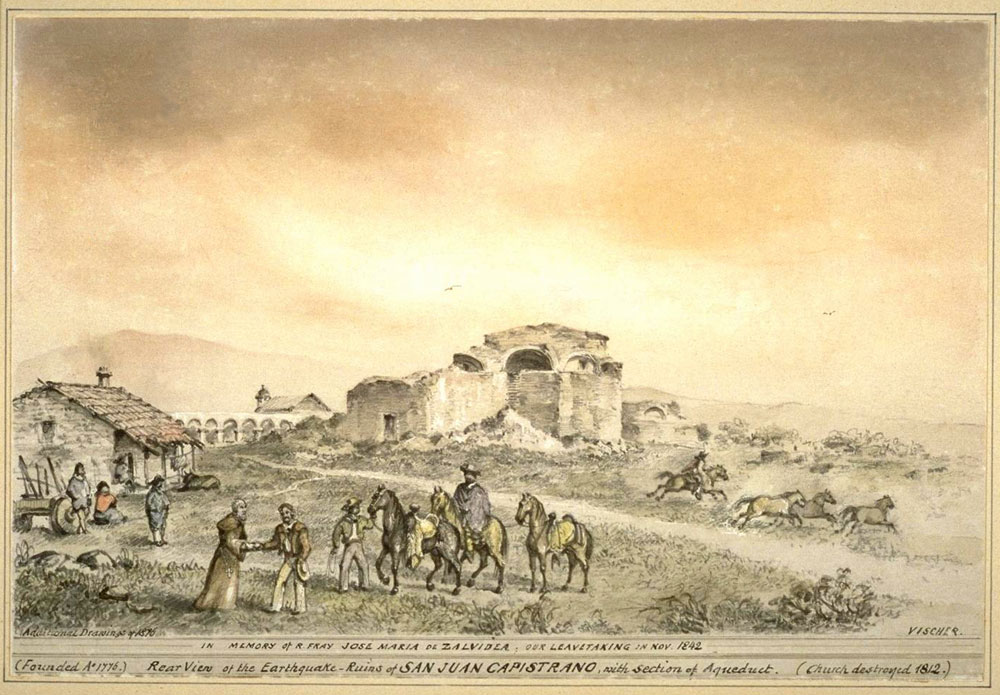

–San Juan Capistrano: A view by Edward Vischer of the area between the old barracks and the ruined stone church.

¶ 92.

–There was another

captain here by the name of Captain Agustin Vicente Zamorano:

Don Agustin obliges us by providing a self-portrait (below).

¶ 93.

–A map of the San Diego

Plaza area.

–he followed the troops to San Luis Rey, where he lived: Below, William Rich Hutton's drawing of Mission San Luis Rey in 1848 (image courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM 43214 20, used by permission.)

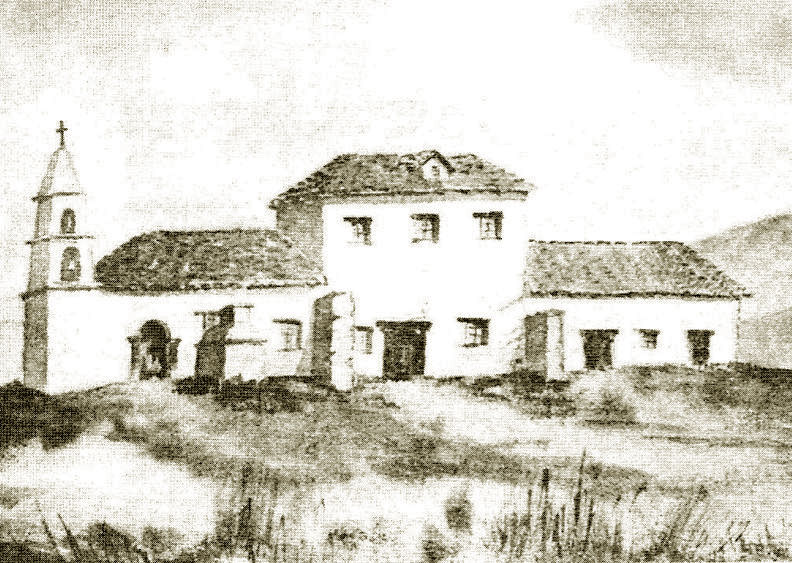

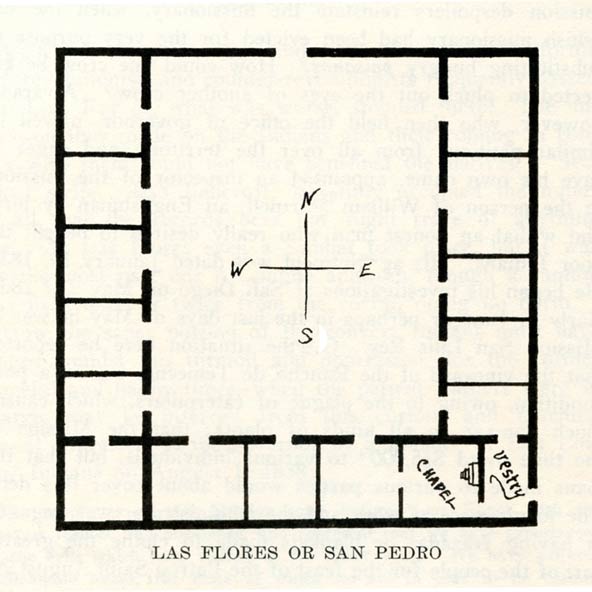

– Las Flores (a rancho belonging to San Luis Rey): Below are the ranch buildings, including the San Pedro Chapel, of the estancia Las Flores on Rancho Las Flores, as they appeared circa 1850. The belltower was prominent enough during its existence that mariners used it as a landmark. "It is situated on an eminence commanding a view of the sea, with the distant islands St. Clemente and Catalina, and overlooking an adjacent level, extending for miles around, covered with thousands of animals grazing" (from Alfred Robinson's Life in California, published in 1846, but this passage refers to Robinson's travels in 1829). Second below is a plan of the Las Flores compound grounds, from Zephyrin Engelhardt's San Luis Rey the King of the Missions. The rancho is Las Flores; the chapel in the Las Flores ranch-house complex is the chapel of San Pedro.

¶ 97.

–General

remarks: "[I]t requires careful examination to know

thoroughly the character of a Mexican. From whatever cause it may arise,

whether from apathy or self-willed obstinacy, from desire to use the power

of action, and not of reflection, which independence has bestowed upon

them, and of which they make a most licentious use; certain it is, that an

examination into the principles of justice is no concern of the partisan.

The feeling of the moment is quite sufficient for his enlistment, either

on the right side or the wrong; and the direction even of his thoughts is

left to the leaders of either faction–I say faction, because that is

the proper term applicable in Mexico, to what in other countries may be

termed party. In Mexico, a thing may be morally right and

politically wrong; and as political dogmas are, for the most part,

unintelligible, by a singular perversion of good feeling they are usually

adopted" (Hardy, Travels in the Interior of Mexico, p. 106).

"[P]ersons of Spanish heritage preserve an intense localismo,

or respect for one's own locale or district, a deep belief in

personalismo, which glorifies the individual over an abstract

principle, religious and familial practices, and an intense

preoccupation with the present, not generally shared by their Anglo

counterparts" (this latter quote from site California During

the Revolution, by Leon G. Campbell).

¶ 101.

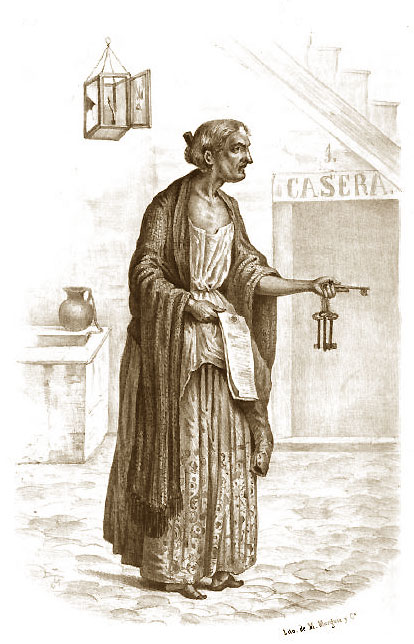

–old lady

Urquides: Perhaps Señora Urquides looked somewhat like

this...

¶ 102.

–the town of Santa

Barbara: Image from Alfred Robinson's Life in

California.

¶ 106.

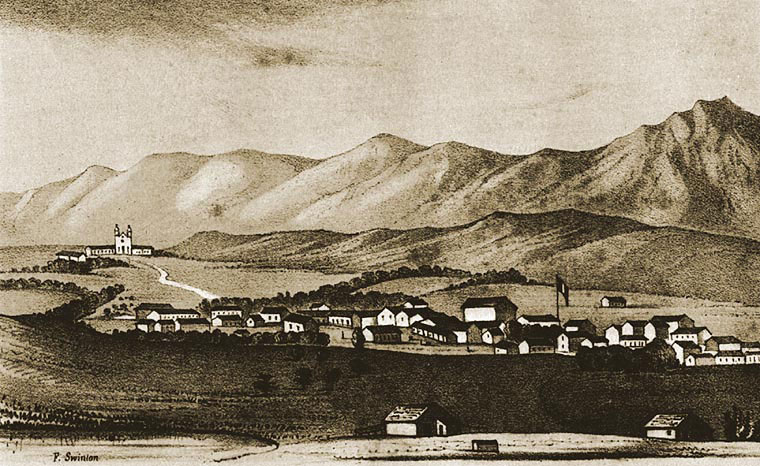

–we [...] arrived at

Mission San Luis Obispo about noon: Below, William Rich

Hutton's view of Mission San Luis Obispo, as it looked in 1850. (Image

courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM

43214 (43), used by permission.)

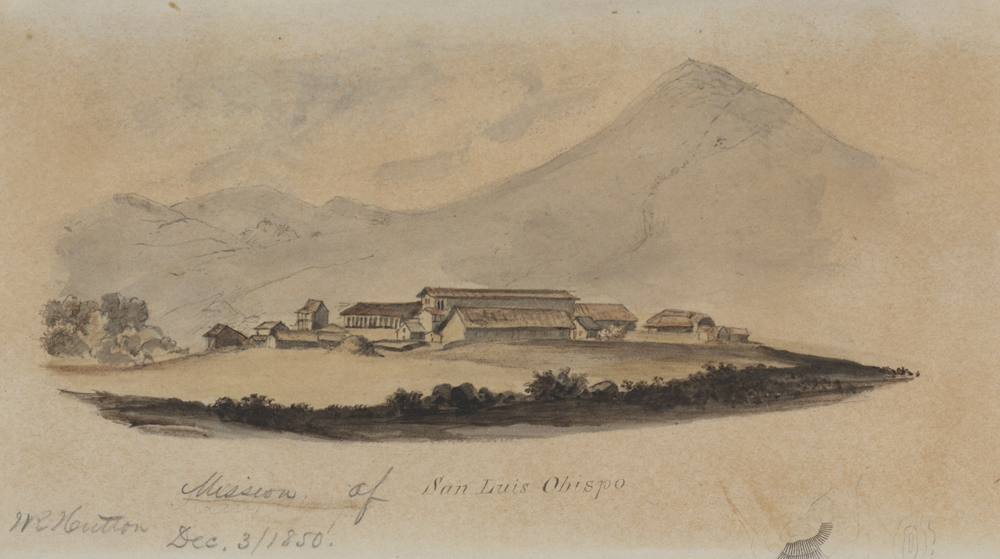

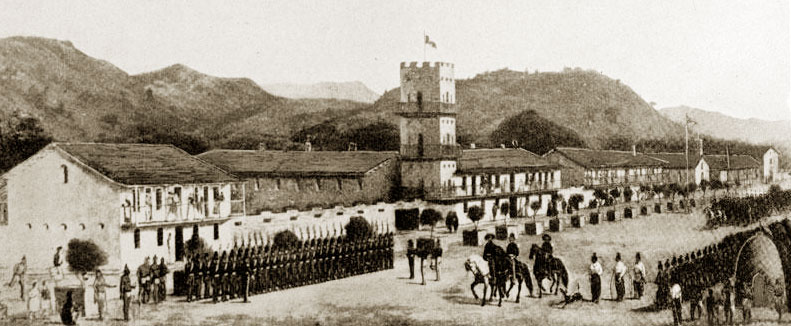

¶ 108.

–In

Sonoma: Below, a look at Sonoma's plaza, with Vallejo

reviewing his men, his residence at center with the castellated tower, and

Mission San Francisco Solano, where the prisoners were held, at right.

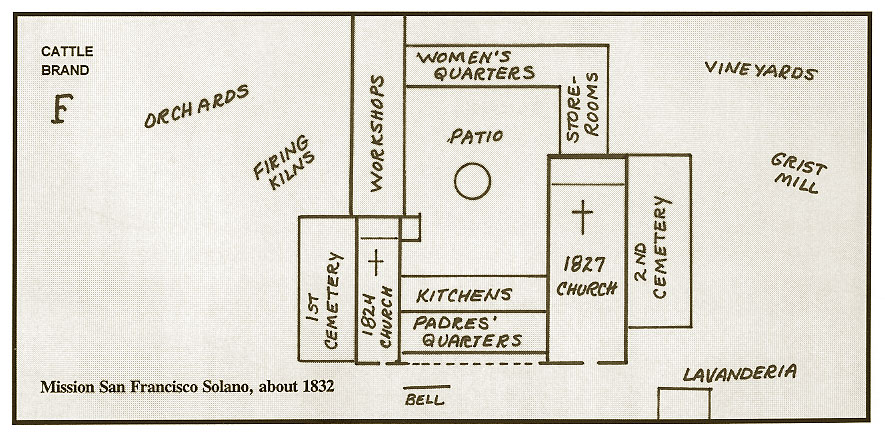

–the hall of the mission: This could refer perhaps to the refectory in the padres' quarters (see below), or possibly to what the old 1824 church was being used for at the time.

¶109.

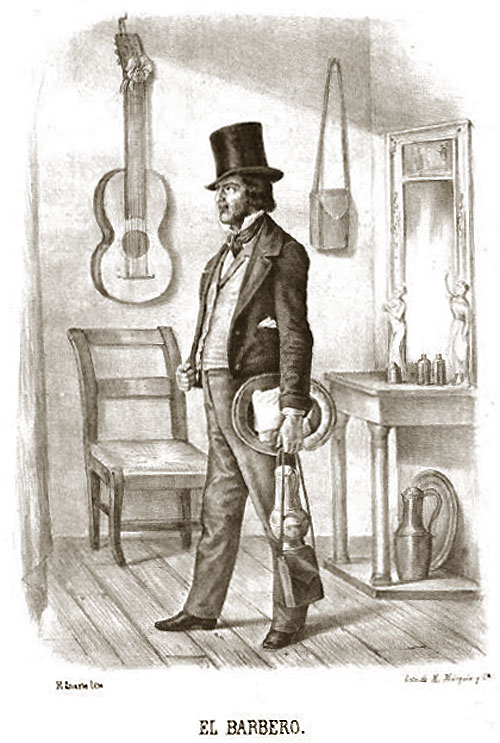

–He was an excellent

barber: Padilla would have been rather younger; but, below,

El Barbero, from the 1855 Los Mexicanos Pintados por si

Mismos.

¶ 110.

–The room was at the

rear of the mission: This was surely a room in the old

monjero or Women's Quarters (see the chart above), the door of

which would indeed have faced south.

¶ 126.

–a series of

dances: At the completion of Juan Bandini's home on the

Plaza in San Diego in 1829, he held a fandango, which was

described by Alfred Robinson in his Life in California: "At an

early hour the different passages leading to the house were enlivened

with men, women, and children, hurrying to the dance; for on such

occasions it was customary for every body to attend without waiting for

the formality of an invitation. A crowd of leperos was collected

about the door when we arrived, now and then giving its shouts of

approbation to the performances within, and it was with some difficulty

we forced our entrance. Two persons were upon the floor dancing 'el

jarabe.' They kept time to the music, by drumming with their feet, on

the heel and toe system, with such precision, that the sound struck

harmoniously upon the ear, and the admirable execution would not have

done injustice to a pair of drumsticks in the hands of an able

professor. The attitude of the female dancer was erect, with her head a

little inclined to the right shoulder, as she modestly cast her eyes to

the floor, whilst her hands gracefully held the skirts of her dress,

suspending it above the ankle so as to expose to the company the

execution of her feet. Her partner, who might have been one of the

interlopers at the door, was under full speed of locomotion, and rattled

away with his feet with wonderful dexterity. His arms were thrown

carelessly behind his back, and secured, as they crossed, the points of

his serape, that still held its place upon his shoulders. Neither

had he doffed his 'sombrero,' but just as he stood when gazing from the

crowd, he had placed himself upon the floor. The conclusion of this

performance gave us an opporunity to edge our way along towards the

extremity of the room, where a door communicated with an inner

apartment. Here we placed ourselves, to witness in a more favorable

position the amusements of the evening. The room was about fifty feet in

length, and twenty wide, modestly furnished, and its sides crowded with

smiling faces. Upon the floor were accommodated the children and Indian

girls, who, close under the vigilance of their parents and mistresses,

took part in the scene. The musicians again commencing a lively tune,

one of the managers approached the nearest female, and, clapping his

hands in accompaniment to the music, succeeded in bringing her into the

centre of the room. Here she remained a while, gently tapping with her

feet upon the floor, and then giving two or three whirls, skipped away

to her seat. Another was clapped out, and another, till the manager had

passed the compliment throughout the room. This is called a son,

and there is a custom among the men, when a dancer proves particularly

attractive to any one, to place his hat upon her head, while she stands

thus in the middle of the room, which she retains until redeemed by its

owner, with some trifling present. During the performance of the dances,

three or four male voices occasionally take part in the music, and

towards the end of the evening, from repeated applications of

aguardiente, they become quite boisterous and discordant. The

waltz was now introduced, and ten or a dozen couple[s] whirled gaily

around the room, and heightened the charms of the dance by the

introduction of numerous and interesting figures. Between the dances,

refreshments were handed to the ladies, whilst in an adjoining

apartment, a table was prepared for the males, who partook without

ceremony. The most interesting of all their dances is the contra

danza, and this, also, may be considered the most graceful. Its

figures are intricate, and in connection with the waltz, form a charming

combination. These fandangos usually hold out till daylight, and

at intervals the people at the door are permitted to introduce their

jarabes and jotas. G– [William Gale] and

myself retired early [...]" Below, we see El Jarabe, by Edouard

Pingret; much further down, we have occasion to picture the

jota.

¶ 134.

–"him men" should

be "his men".

¶ 135.

–jumped onto the

wall: Below, some L.A. walls of ca. 1850, just about a block

away from the location where the incidents of Botello's narrative were

taking place.

¶ 137.

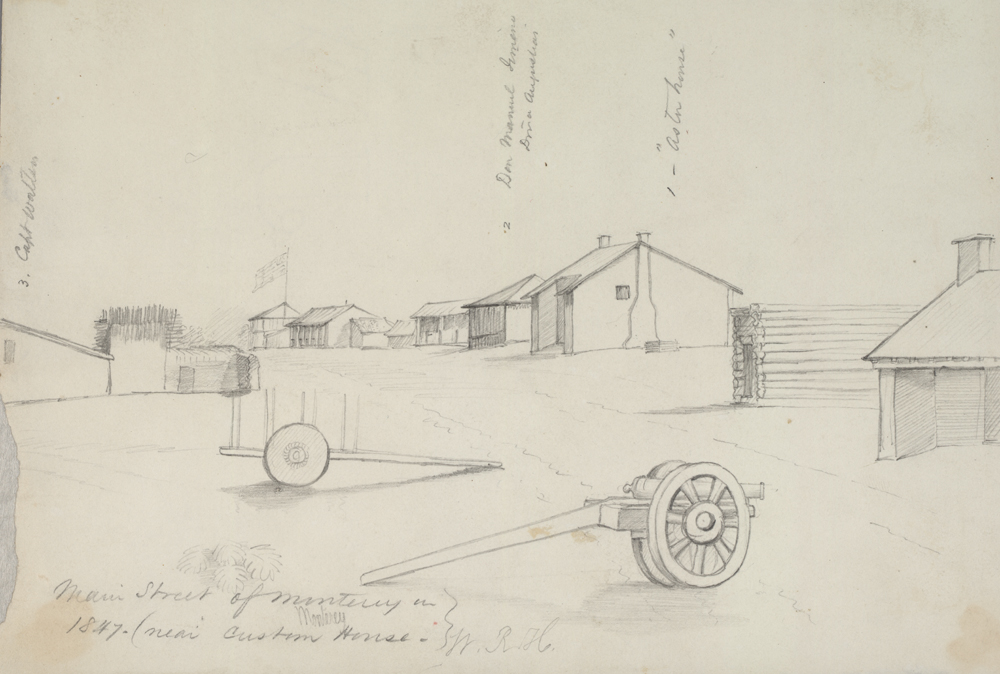

–I went to

Monterey: Below, William Rich Hutton's drawing of the main

street of Monterey in 1847. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San

Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (53); used by permission.)

–David Spence: David Spence was perhaps the merchant Mr. Spence whom author Hardy, of Travels in the Interior of Mexico, met in Guaymas in February, 1826. "His face I thought looked sallow, and his body wasted, from the effects of poison, which, as he assured me, had been administered to him at Pitic. He is married to a lady of the country. He possesses a great deal of hearsay information, although, perhaps, he is by no means qualified to form an opinion of his own" (p. 90).

¶ 138.

–"to support of"

should be "for support of".

¶ 142.

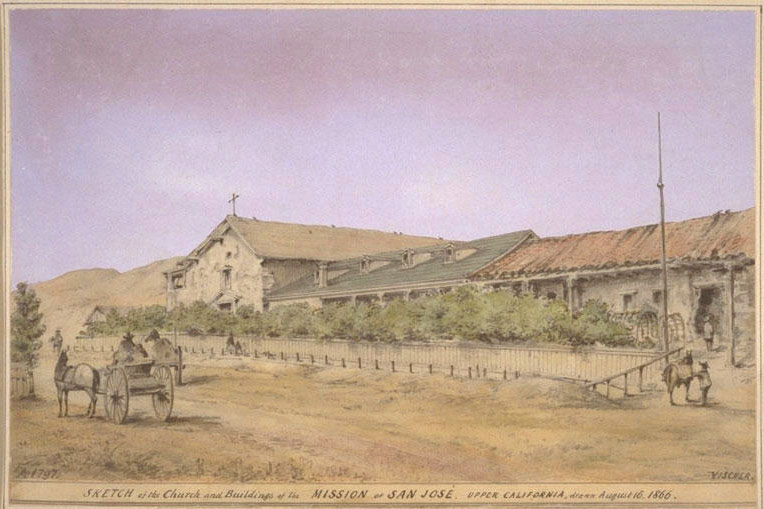

–Castro established his

headquarters at Mission San Jose: Below, Mission San Jose,

sketched by Vischer in a somewhat dilapidated state (the mission, not

Vischer).

¶ 155.

–"Manso, who

Spaniard" should be "Manso, a Spaniard".

¶ 165.

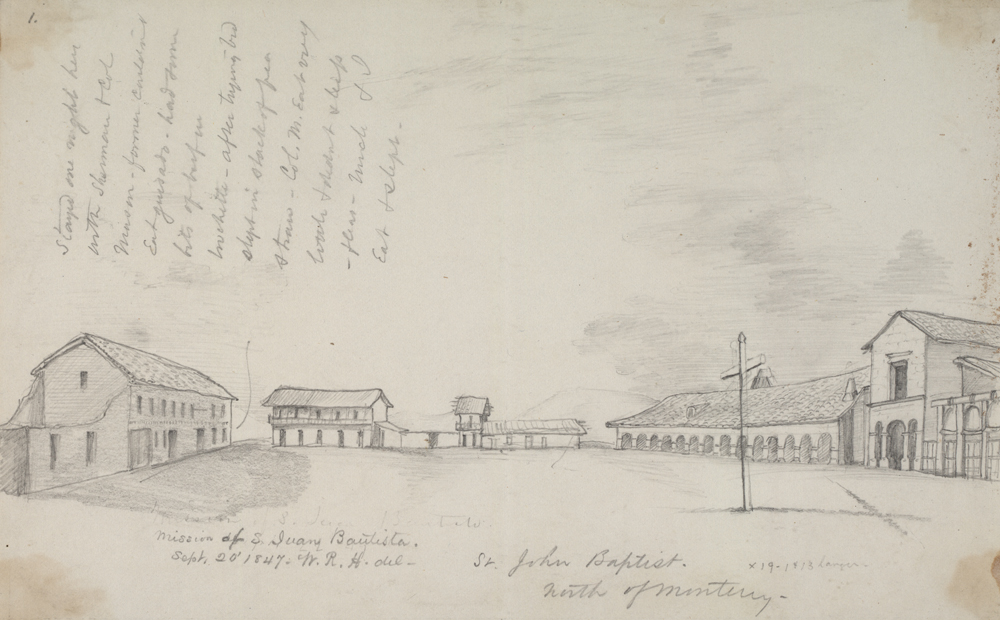

–They arrived in San

Juan Bautista: Below, William Rich Hutton's drawing of San

Juan Bautista in 1847. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino,

California, call number HM 43214 (59), used by permission.)

¶ 166.

–through the Sacramento

region where Captain Sutter had his establishment: William

Rich Hutton visited Sutter's Fort in April, 1849. (Image courtesy the

Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (91),

used by permission.)

¶ 169.

–A closing

parenthesis should be placed after "Santa Barbara."

¶ 178.

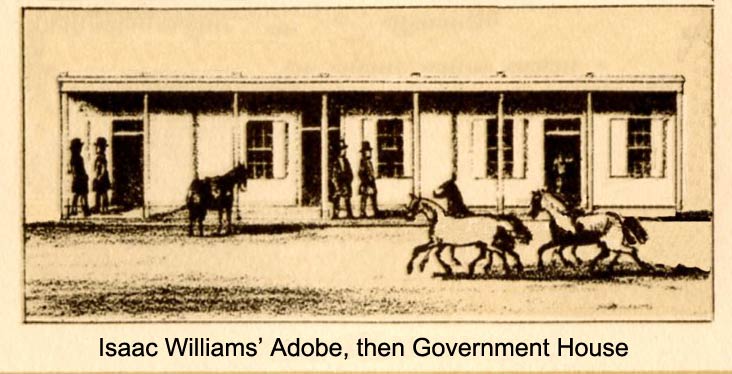

–and resided at the

government house: Below, a rendering of Government House,

which had been the Isaac Williams adobe, and which would be the first

incarnation of the Bella Union Hotel. I indeed have deconstructed an 1857

view of the Bella Union Hotel, taking off its second story so that the

building is as it would have been during the pre-Yankee era. In 1858, the

original structure would be demolished and replaced with the brick Bella

Union Hotel building which is more familiar to historians.

¶ 181.

–"groups or

three" should be "groups of three".

¶ 184.

–commanded by Don

Benjamin D. Wilson: We see Don Benito below:

–the house: This was Isaac Williams' ranch house, which Alfred Robinson had visited in mid-1842 and then mentioned in his book Life in California (p. 204): "At the farmhouse of Isaac W– we stopped awhile to rest our horses. It is the most spacious of the kind in the country, and possesses all desirable conveniences."

¶ 188.

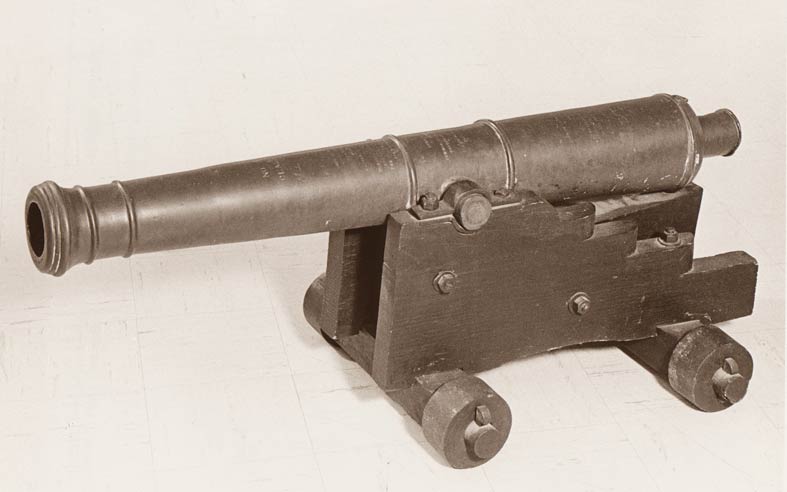

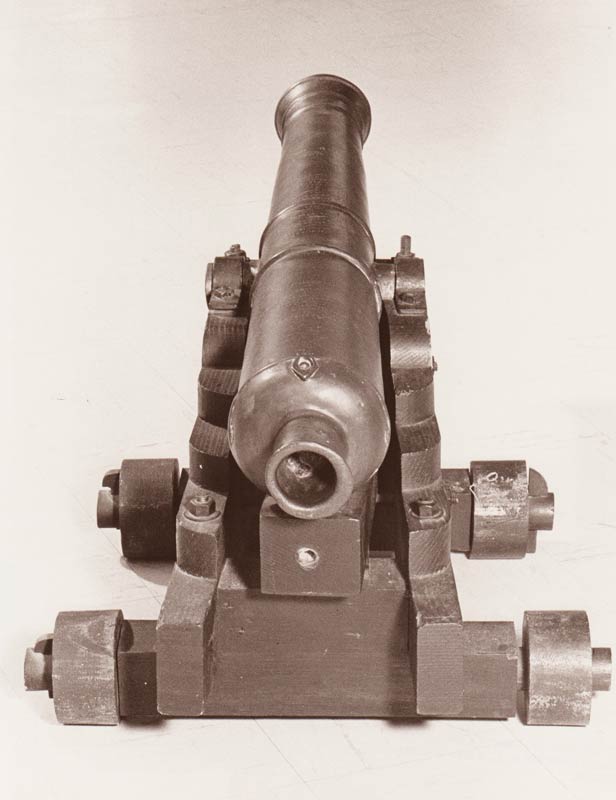

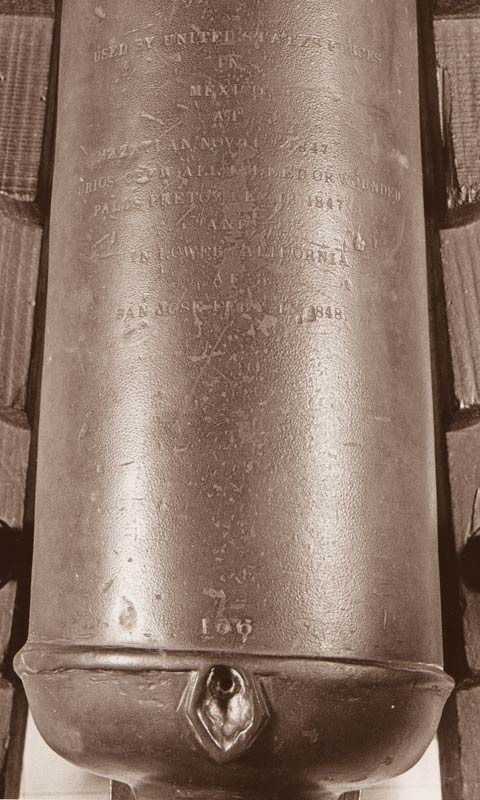

– this

cannon: Not many participants in the Californio

battles are still around; but we are fortunate that "this cannon," the Old

Woman's Gun alias El Cónico, is! Franklin G. Mead has

collected information on, and pondered well, the gun, and generously

offers these remarks: The Old Woman's Gun is a quite large swivel gun;

but it is, indeed, a swivel gun (in contradistinction to a field gun).

Description: Bronze, smoothbore, 4 pounder, cannon tube, 43½ inches

overall in length; bore 2.77 inches diameter; 4½ inch muzzle section

length; tube 4 inches in diameter at the muzzle astragal; 16 inch chase

section; 6 inches between 3rd and 2nd reinforce; 9½ inches across at

trunnions. I looked at the vent carefully and found nothing wrong with it.

The "wide" vent referred to by Antonio Maria Osio likely stems from

familiarity with small arms but not cannons. The wide somewhat

lozenge-shaped hole leading to the actual vent serves as a funnel and wind

guard (shield), which minimizes getting powder all over the hot breech of

the gun. The actual vent, the small round hole in the photo, appears to be

in good and serviceable condition. A flintlock musket, rifled musket, or

pistol all have vents, and the pan serves the same purpose as the vent

shield on the cannon, but looks very different. The Old Woman's Gun did

not have any igniting device available and was therefore fired with a lit

cigarette. This clearly indicates that there was no appreciable danger

firing the gun. Caliber-inch: See Botello's Annals, page 258, notes

to ¶ 188 this cannon–"Jose Francisco de Paula

Palomares states that it was bronze and of about six inch caliber." The

Old Woman's Gun was a four pounder with a bore diameter of 2.77 inches and

a length of 41.05 inches, with windage of 0.12 inches, using a lead

cannonball weighing 4.0036016 pounds and 2.65 inches in diameter. The gun

was incorrectly stated by Palomares to be six inch caliber. We know that

the bore diameter was 2.77 inches and not 6 inches. We know that the

cannonball was lead because a cast iron cannonball of 2.65 inches in

diameter would weigh only 2.4641885 pounds. The gun itself probably weighs

about 140 pounds. The socket at the rear of the breech is for a large

round peg used to aim the gun. After being turned over to the U.S. by the

Californios, the Old Woman's Gun was used in battle by U.S. forces

in 1847 and 1848 in Mazatlan etc., as recorded in the engraving on the

piece. It is now in the U.S. Naval Academy Museum at Annapolis, which

kindly supplied the black and white photos which follow. Equally kind was

the permission granted for me to use the color collage of photos below,

which are Copyright 2014 Springfield Arsenal LLC.

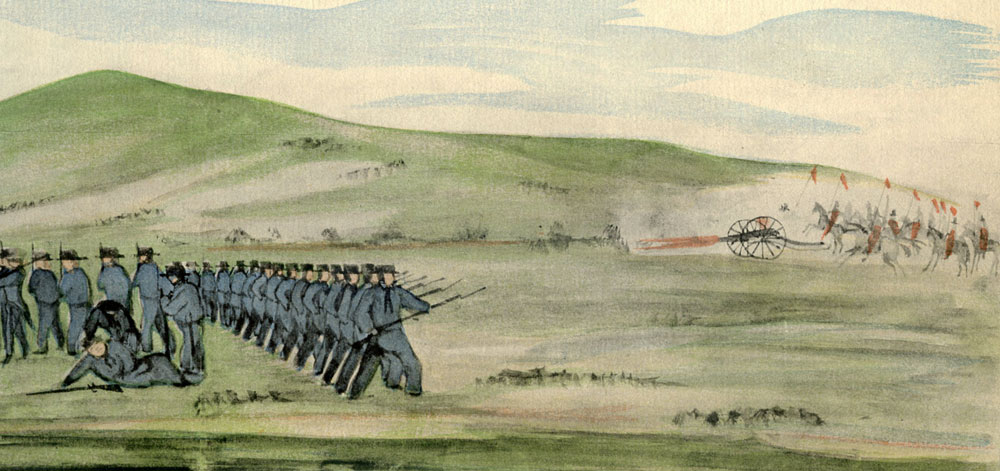

¶ 189.

–Aguilar fired again,

with the same success: Below, a detail from Gunman Meyers'

depiction of the Battle of Dominguez Rancho. He was perhaps not personally

present, as he shows a standard field gun on a standard carriage rather

than the Old Woman's Gun on its modified ox-cart, and shows no presence of

the mustard plants which were so important to the Californios as

providing cover. Civil War historians will perhaps be reminded to some

degree of Miller's Cornfield at Antietam.

¶ 190.

–"they could some him his

things" should be "they could send him his things".

¶ 194.

–General

remarks: Louis Robidoux, one of the Chino prisoners, makes

some interesting remarks in a letter dated May 1, 1848. Referring to

Flores at this juncture, he writes, "There was at that time a party which

always spied on him, which obstructed his plans and, when it was

necessary, opposed his particular designs. This party, knowing that our

departure was against the general interest of the Californians, and also

fearing a reprisal from the Americans, opposed Flores and formed a plan

(with help from us prisoners, that is to say with our money) to remove him

from office. That occurred on the evening before we were to leave for the

capital [Mexico City]." (This excerpt from article "Louis

Robidoux: Two Letters from California, 1848," in Southern California

Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 2, Summer 1972.) Who was the spy? I would be

inclined to point in the direction of Jose Antonio Ezequiel Carrillo. If

Flores had the same suspicion, it would go far to explain his attitude

toward Carrillo in this period.

¶ 195.

–General

remarks: As president of the Assembly, Botello was thus next

in the line of succession to be governor, his high-water mark in his

career.

¶ 201.

–a location known as

Los Barrancos: Vischer obliges us with a view.

¶ 207.

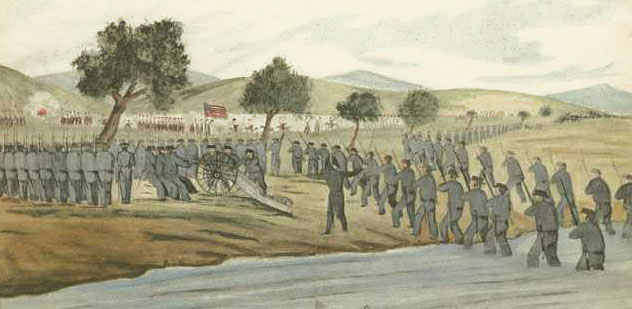

–The Battle of Bartolo

Pass: The moment of the battle when the Californios

were attacking as the Yankees were crossing the river, Commodore Stockton

directing at center. Sketch of 1847 by Gunner William H. Meyers, much

cropped at top (lots of cloudy sky), acquired with other of Meyers'

sketches by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and published in the 1939 book

Naval Sketches of the War in California. Diego Sepulveda is about

to call out HALT!, sending the Californios into confusion, and

snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. Juan Avila, in his Notas

Californias for Bancroft, recalls observing this moment of the

battle: "There was a movement [by the Californio forces] which

broke the American phalanx[,] which was in grave danger of

destruction, when Don Diego Sepulveda gave the order to halt to the

Californians who had jumped down to fall upon the Americans. Already

some of the Californians on horseback had broken into the square

[of Americans] and on their return said that the Americans were

taking refuge beneath their carretas" (translation by Lt.

Alfonso Yorba in Orange County History Series Volume Three,

1939). It is interesting to speculate on what would have happened had

Sepulveda not halted the Californios and thrown them into

confusion. Supposing that Stockton had surrendered, as it seems he was

on the point of doing, and the whole Yankee force been taken

prisoner, likely they would have been held as guarantees of acceptable

conditions for the Californios pending the outcome of the war

in Mexico.

¶ 213.

–The Battle of El

Llano de las Lagunas, alias the Battle of La Mesa: A picture,

slightly cropped, of the battle, by Gunner William H. Meyers, watercolor

of 1847, acquired with other of Meyers' sketches by Franklin Delano

Roosevelt, and published in the 1939 book Naval Sketches of the War in

California. The artist shows rather more carnage than actually

occurred. We're looking from the south; the Pueblo of Los Angeles would be

to the left, across the (unseen) river (the shrubbery at back left perhaps

gives a hint of the riverbed). The eminence at back is the site of today's

Boyle Heights; today, we would see the Santa Ana Freeway curling around

the base of the "mesa."

¶ 218.

–"our lives, our

libery" should be "our lives, our liberty".

¶ 224.

–and then go to San

Jose to spend it on bad habits: Referring to ca. 1830, Alfred

Robinson writes, "The town of St. Jose [sic] consists of about one

hundred houses; it has a church, court-house, and jail. [...] The men are

generally indolent, and addicted to many vices, caring little for the

welfare of their children, who, like themselves, grow up unworthy members

of society. Yet, with vice so prevalent amongst the men, the female

portion of the community, it is worthy of remark, do not seem to have felt

its influence, and perhaps there are few places in the world, where, in

proportion to the number of inhabitants, can be found more chastity,

industrious habits, and correct deportment, than among the women of this

place." Ca. 1846, Edwin Bryant writes (in What I Saw in

California), "The buildings of the Pueblo [of San Jose], with few

exceptions, are constructed of adobes, and none of them have even the

smallest pretensions to architectural taste or beauty. The church, which

is situated near the centre of the town, exteriorly resembles a large

Dutch barn. The streets are irregular, every man having erected his house

in a position most convenient to him. [...] During the evening I visited

several public places (bar-rooms), where I saw men and women engaged

promiscuously at the game of monte. Gambling is a universal vice in

California. All classes and both sexes participate in its excitements to

some extent. The games, however, while I was present, were conducted with

great propriety and decorum so far as the native Californians were

concerned. The loud swearing and other turbulent demonstrations generally

proceeded from the unsuccessful foreigners. I could not but observe the

contrast between the two races in this respect. The one bore their losses

with stoical composure and indifference; the other announced each

unsuccessful bet with profane imprecations and maledictions. Excitement

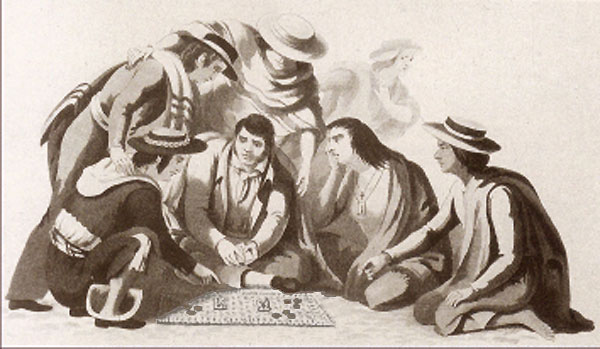

prompted the hazards of the former, avarice the latter." Below, Claudio

Linati's depiction of a group gambling at the game of Monte.

¶ 225.

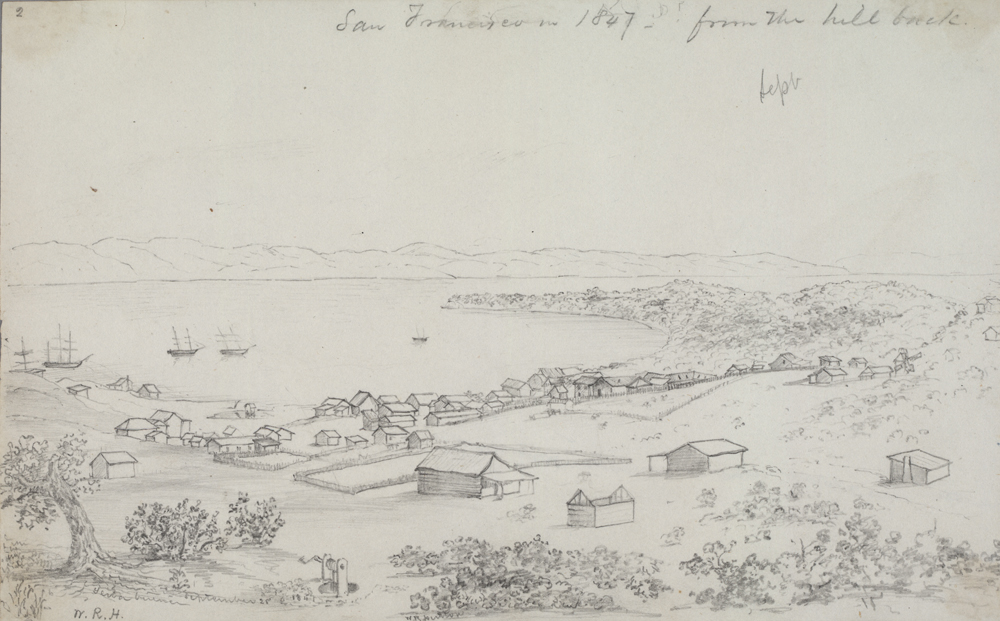

– I went to San

Francisco to buy goods: Willliam Rich Hutton shows us how San

Francisco "from the hill back" looked in 1847. (Image courtesy the

Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (81),

used by permission.)

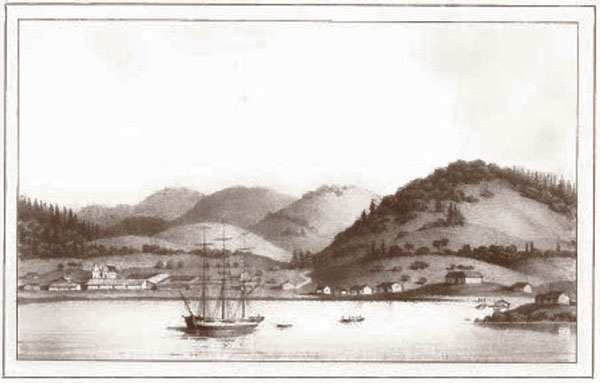

–He advised me to go to Monterey, and board a small vessel: Below, Duhaut-Cilly's view of Monterey, 1827, from the bay. The presidio compound with its chapel can be made out towards the left.

¶ 226.

–and put my people to

work.

¶ 231.

–"[personal["

should be "[personal]".

¶ 242.

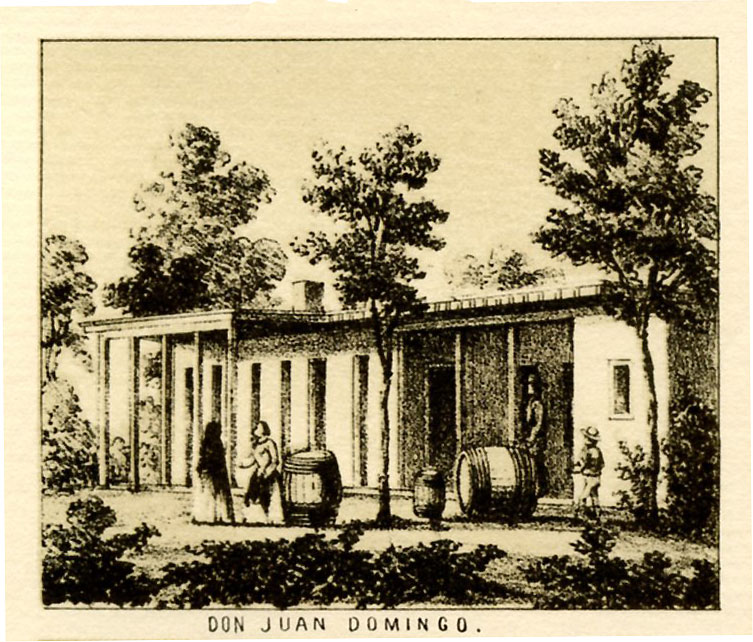

–Juan Domingo, another

German who lived nearby: Below, the home of Juan Domingo, as

it appeared in 1857.

• This section refers to information and/or text in the footnotes:

¶ 1.

–Narciso

Botello: Courtesy the kindness of Narciso's great great

grandnephew Stan Botello, I can offer some new information. Narciso's full

name was Jose Narciso Rafael Guadalupe Botello. He was baptised on

November 3, 1810, in Alamos, Sonora, Mexico. His parents were Vicente

Antonio Botello and Maria Francisca Miranda, listed on the baptismal

paperwork as residing in Minas Nuebas, a mining town about 7 miles west of

Alamos. The sister who is probably the one who went to Los Angeles with

Rafael Guirado was Maria Marcela Rafaela Botello, baptized February 28,

1807. He had another older sister who was named Maria Dolores Sacramento

Rafaela Botello, baptized April 22, 1803, and buried in Alamos June 4,

1838. His younger sister, mentioned in the text as Brigida, was Maria

Brigida Vicenta Botello, baptized October 16, 1821. Narciso's brothers

were Pedro Ysais Botello, who married Maria Concepcion Eligia Ramirez in

L.A. on December 12, 1858, and Jose Refugio Botello, who married Maria

Ygnacia Ramirez in L.A. on October 5, 1884. These two brides were sisters,

and, while not, as wrongly stated in Narciso's obituary, and in other

texts taken from that obituary, the daughters of a General Ramirez,

they were indeed the daughters of Alferez and Lieutenant Jose Maria

Ramirez, who himself appears in Narciso's Annals. Lt. Ramirez was married

to Maria Dolores Palomares, the sister of Ygnacio Maria Palomares (who

finds mention in Narciso's Annals). Narciso's paternal grandparents were

Vicente Miguel Cibiriano Botello and Juana Ysabel Siqueyros; these of

course were also the parents of Narciso's aunt mentioned in the text,

whose full name was Maria Ysabel Ursula Botello. Aunt Ysabel's husband

Jose Guirado (seen also as "Josef") had died April 12, 1819, in

Alamos.

¶ 9.

–latterly kept a

saloon: Rice's saloon was located on the west side of Main

St. between the later sites of the Downey Block and the Lafayette Hotel, nearly directly across from where Commercial St. opened on the east onto Main.

¶ 10.

–Don Antonio

Rocha: At the end of the entry, delete the

"ò".

–entry on the Rectory:

"normaly" should be "normally".

–entry on Antonio

Reyes: Delete the space before "possibly".

¶ 35-36.

–General

remarks: "Padrés" should be "padres"; and "themselves

entitles to promotion" should be "themselves entitled to promotion".

¶ 51.

–entry on playing

cards: "was the the guards" should be "was that the

guards".

¶ 84.

–Vicente

Elizalde: "*Star" should be "Los Angeles Star". Pamela

Filbert, a descendant of Vicente Ferrer Lisalde, very kindly corrects me

that the Vicente Lisalde who married Pilar Blanco in 1859 was not

our Vicente Ferrer Lisalde, and so that sentence may be deleted from

the footnote; and she adds that Vicente Ferrer Lisalde was a member of

L.A.'s first (volunteer) police force under Capt. (and Dr.) Alexander W.

Hope, that he subsequently served as one of the four constables (in 1852),

that he married Minerva Jane See (widow of William Corlew) on September 4,

1888, who filed for divorce exactly a year later, and that Vicente's death

was announced in the Los Angeles Herald on August 4, 1901. Many

thanks to Ms. Filbert for generously sharing this information!

¶ 86.

–We hid ourselves

in the mustard plants: "Lugo, says" should be "Lugo

says,".

¶ 100.

–Jose M. Ramirez:

I can add to my note about Ramirez in the book that Bancroft

(History 3:16) tells us that, "in a personal quarrel," he killed

the cruel El Capador Vicente Gomez in San Vicente, Baja California,

probably about September, 1827 (more about Gomez in a moment); and in

July, 1828, that he was in San Diego, not making Auguste Duhaut-Cilly very

happy: "Only a few minutes after we had dropped anchor, an officer named

Ramirez appeared on shore and called for us to send a boat; this I sent

manned by four seamen, but they returned without him, reporting that he

insisted on the presence of an officer. Suspecting a misunderstanding, I

myself went on shore and asked him why he had not come in the boat. 'I

judged it not fitting,' said he. 'You should have sent an officer to

receive me.' This pretentious and unreasonable demand set me greatly

against him. 'The boat I sent you,' I responded, and which I have just

come in, should be quite sufficient for the messenger of a government that

does not even have a canoe at its disposal. Such vanity does not please

me; if you have orders to take my declaration [of his cargo] you

may embark with me, but there will be no officer to accompany your return

to land. You now have the privilege of choosing what you should do.'

Seeing how I meant to deal with him, he made some awkward excuses for his

conduct, claiming that he had been badly treated by some other captains.

He finally decided to come on board, and after he had accomplished his

mission I sent him back to shore with no other retinue than the boatmen. I

was all the more uncompromising with this republican, knowing that he

enjoyed a bad reputation, having recently been accused of murder. I was

not displeased to find occasion to show my small respect for him" (from

Duhaut-Cilly's A Voyage to California, the Sandwich Islands, and Around

the World in the Years 1826-1829, pp. 194-195, translated by August

Frugé and Neal Harlow, University of California Press, 1997, 1999).

As to Gomez, the interested reader may revel in the details of his

criminal career in Hardy's Travels in the Interior of Mexico. For

instance, "This wretch was so atrocious in his cruelty, that he spared

neither sex nor age. At that period he had a thousand men under his

directions, all as ferocious as himself. He is still [1826] a

half-pay Colonel in the Mexican army! His station, before his exile, was

chiefly about the Peñou and San Martin, between Puebla and Mexico

[City]. At first he made war only against the old Spaniards; but when

these became scarce, he turned his hand against his own countrymen, by way

of keeping up practice! And there are living instances at Puebla which

attest the success of his skill. He once took a prisoner whom he ordered

to be sewed up in a wet hide, and exposed to the sun, by the heat of which

it soon dried and shrunk, and the wretched victim died in an agony which

cannot be described [etc., etc.]," (p. 122 in Hardy). Gomez spent a

short time in exile in California before his demise at the hands of

Ramirez.

¶ 109.

–Jose Ramon

Carrillo: "(*Star)" should be "(Los Angeles Star)",

and "heredetements" should be "hereditaments".

¶ 112.

–a sentinel by the name

of Higuera: Franklin G. Mead carefully researched the

parentage of Jose Ygnacio Teodoro Higuera, and, citing and supplying much

source material in support, kindly corrects the name of his mother to

Maria Ambrosia Pacheco, who, he writes, "was the mother of Jose Ygnasio

[as spelled on the baptismal record] Higuera. The source of the

error citing Maria Barbara Pacheco as the mother of Jose Ygnacio Higuera

was Mission San Carlos baptism record #2856, 12 November 1812, where Fray

Juan Amoros incorrectly recorded Maria Barbara Pacheco as the spouse of

Jose Antonio Higuera and the mother of Jose Ygnasio Teodoro Higuera. Both

Maria Barbara Pacheco's were already deceased when Jose Ygnasio Higuera

was born. [...]"

¶ 140.

–General

remarks: "dislilke" should be "dislike".

–The wealthy ranch-owners and others: Is this a wealthy ranch-owner (below)? He might be among "others." (From the 1855 Los Mexicanos Pintados por si Mismos.)

–Francisco Rico: We can narrow the possible date of Rico's wedding to August or September of 1846; and it took place in Los Angeles.

¶ 157.

–Don Antonio Jose

Cot: "far Callao, Peru" should be "for Callao, Peru".

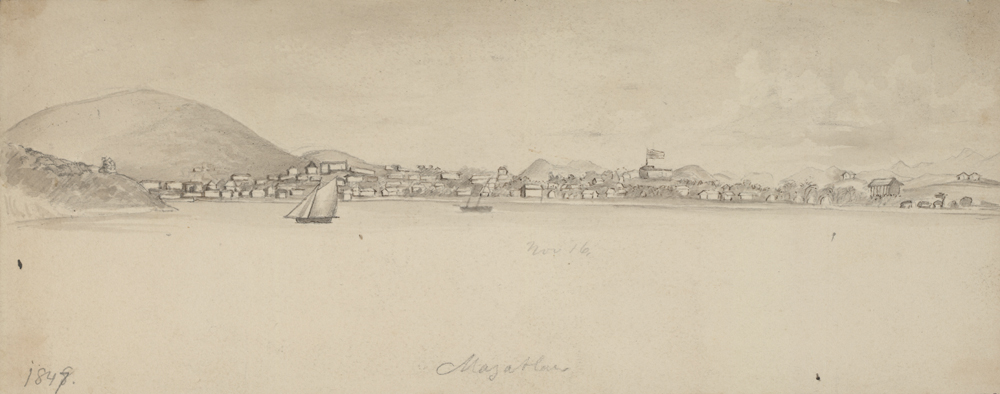

¶ 160.

–sailed for

Mazatlan: Below, Mazatlan in 1847. (Image by William Rich

Hutton, courtesy the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, call

number HM 43214 07 recto, used by permission.)

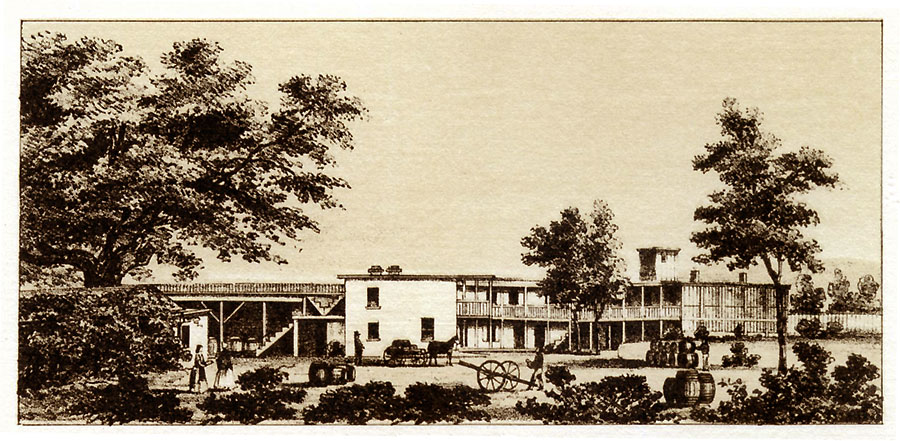

–to get help from Jean Louis Vignes: Vignes–sometimes called Don Aliso from the great Aliso tree on his property–lived at what would become the Aliso Winery on Aliso Street. Vignes' place had also been where the vigilantes in the Huilo Feliz/La Chala case had met to plan their doings. We see below how the property appeared in 1857, the Aliso tree still going strong.

¶ 163.

–the famous mercury

mine New Almaden: William Rich Hutton provides us with an

image of the New Almaden Mine. (Image courtesy the Huntington Library, San

Marino, California, call number HM 43214 (73), used by permission.)

¶ 164.

–showed up in

Monterey: "a grnd dinner" should be "a grand dinner".

¶ 168.

–Eugenio

McNamara: "for a grant of land n California" should be "for a

grant of land in California".

¶ 178.

–The band played a

while: "baggage ammunication" should be "baggage

ammunition"; "later that year" should be followed by a comma.

¶ 183.

–Francisco

Cota: "be in the hands on Gillespie" should be "be in the

hands of Gillespie". Below, we see some of Gillespie, but not his

hands.

¶ 184.

–the operations and

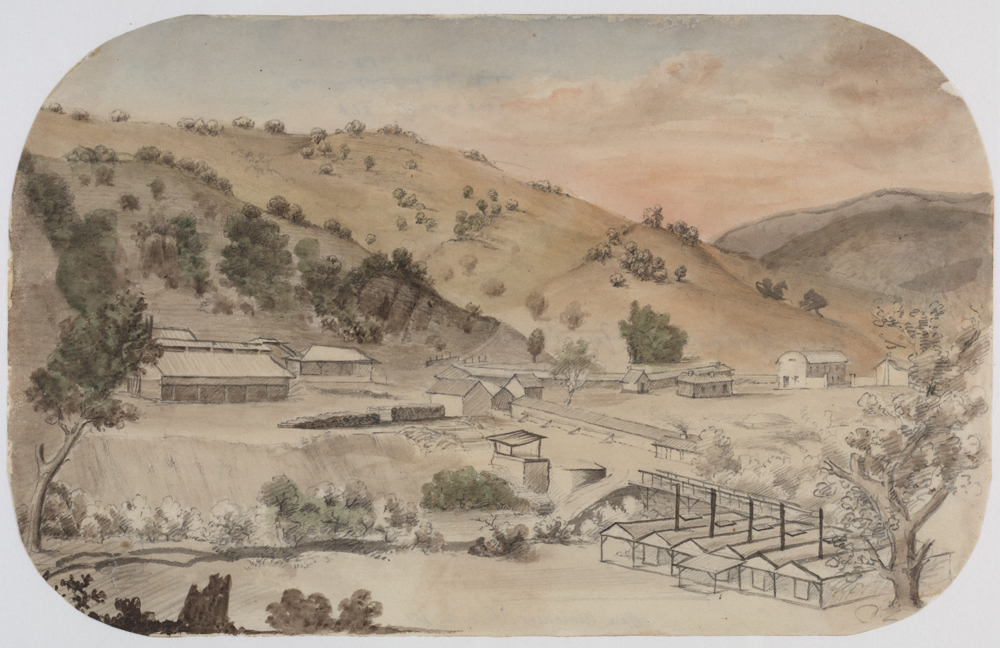

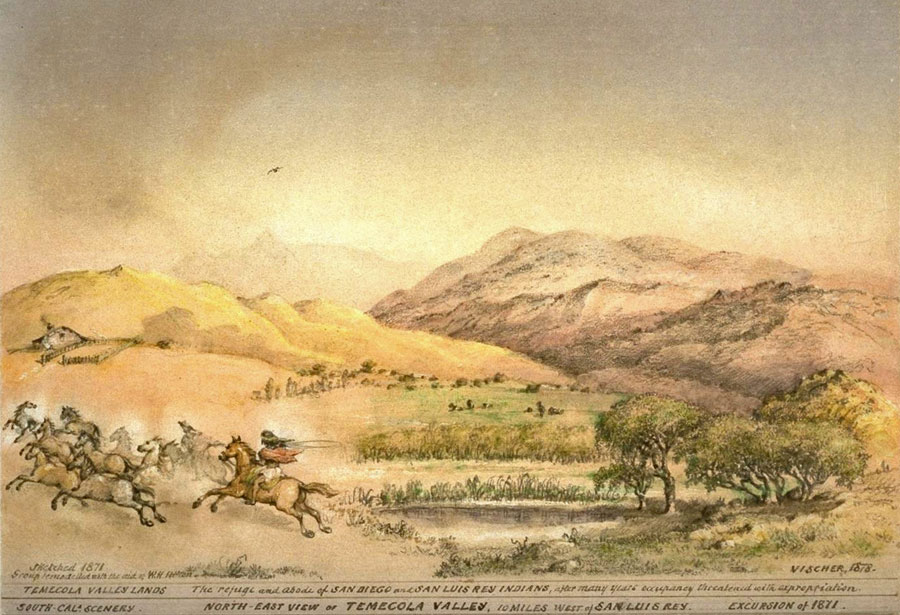

aftermath of the Temecula Massacre: Below,

Temecula–Vischer's "Temecola"–as he saw it in 1871.

¶ 212.

–the

ponds: "El Llano de la Lagunas" should be "El Llano de las

Lagunas".

¶ 229.

–Don Mariano

Bonilla: "Figueroa that he shold" should be "Figueroa that he

should"; and "he wold say that the funds" should be "he would say that the

funds".

¶ 241.

–or perhaps was expert

at dancing the Jota: Below, the Jota Aragonesa.

Appendix, p. 291: "were holed in the cane" should be "were holes in the cane".

• •

•

We bid goodbye to Narciso Botello and our visit to the Mexican era of California with an image of Mexicano prosperity. El Hacendero y su Mayordomo, by Carl Nebel, 1836. And I bid my patient readers, and the impatient ones too, adios.

• You may also find interesting information and images at my related site for my book The Bandini Papers. To visit it, click on the image below:

• My other Old California books: