"If my week is so busy that I don't have even one hour that I can take to devote to other people, then I'm fooling myself that unimportant things are important."

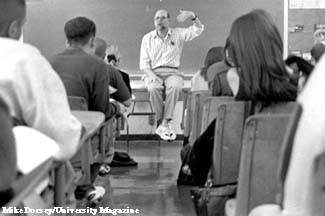

This is how Warren Weinstein feels about his life and its importance. Some may know Weinstein as a fourth-year instructor at Cal State Long Beach in the philosophy department. Aside from the busy life of teaching and being a single parent, Weinstein still finds time to volunteer as a hospice worker.

The hospice program in the United States is designed for the home care for people who are dying. In the U.S., the dying are kept at home. Other countries keep the dying in hospitals.

According to Weinstein, 52, a hospice patient needs a 24-hour care giver who lives there with the person. Nurses, health aids, chaplains and volunteers come and go throughout the day. This is where Weinstein comes in.

He became involved in the hospice program when a little girl, who was a friend of his, was dying. "If I am so self-important that I think that I don't have anytime at all to help somebody else, then I'm losing touch with reality," he said. "I'm sort of floating up in the air. It's real nice to just be pulled back down."

Weinstein enrolled in a class to learn how to be a hospice volunteer. He wanted to be able to offer more when he would visit with his friend, Stephanie. She died while he was in training.

Being a college instructor and a single parent may appear to be

overwhelming,

although Weinstein stresses the importance of volunteering.

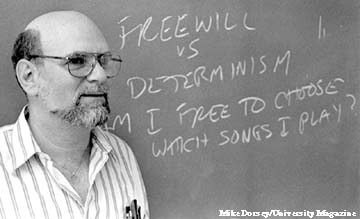

"The truth is that the stuff that I do during the week isn't all that important," Weinstein says, referring to the everyday details of life.

His experience of dealing with death and dying helps keep things in a clear perspective for him. It reminds him of what is important.

Furthermore, Weinstein explains that often when a person learns that they are terminally ill, the people around that person begin to lose contact.

"Most people are freaked out by the fact that somebody is going to die," reasoned Weinstein. "Family, friends, neighbors - they don't want to go see that person who is dying, because it makes them afraid of dying. 'If they're dying I might die,' and that's, uncomfortable."

Weinstein says visiting with these people gives them a sense of human company and contact. He remarked that the visits remind the patients they are not dead yet. His fearless attitude of dying makes the patients question why they are afraid.

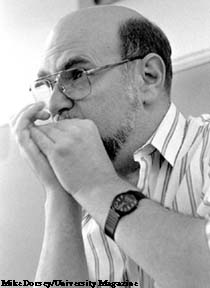

One memorable experience that Weinstein recalled was with his first patient. While visiting a man with lung disease they talked for a little bit but stopped because it became too hard for the man to talk. So Weinstein played his harmonica for the man instead.

Afterwards, he read a little to him until the man fell asleep. Then they both just sat there together as the man napped. When the man's wife returned, she asked how it went. The man replied that it was great. He said that first they communicated in words, then in music, and then they spent the rest of the day communicating through silence. The man had explained the exact same thing that Weinstein had experienced from the visit.

"For him to articulate, to say, just exactly what I had experienced gave me a real confidence that my being there, and being unable to carry a conversation with him didn't diminish the importance of our visit," expressed Weinstein.

Becoming a hospice volunteer requires nine weeks of classroom training. Weinstein explained that it takes a special type of person to volunteer as a hospice worker. "Generally, the thing that hospice volunteers have in common is they have a genuine desire to want to give something back."

Warren Weinstein volunteers at least one hour a week as a hospice worker in addition to his regular duties as a college instructor and single parent.