THE FUTURE AS ANTHROPOLOGY

SOCIALISM AS A HUMAN ECOLOGICAL CLIMAX

by

Eugene E. Ruyle

Department of Anthropology

California State University, Long Beach

Long Beach, California 90840

Abstract

This paper

views cultural evolution as a form of ecological succession, in which the

progressive development of the forces of production and class struggle lead to

a succession of human ecological types. It is suggested that this succession

may culminate in a world socialist system. The Marxian analysis of capitalism

and the transition to socialism is briefly presented and articulated into a

more general theory of cultural evolution. The implications of this perspective

for contemporary Anthropology are discussed.

NOTE 2009: This

is my paper as originally written in 1977. It has been scanned, OCR-ed,

spell-checked, and re-formatted. Only these minor changes have been made.

Introduction

When Marx and

Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto, the idea of socialism was pretty much

confined to a few small sects in Western Europe. Today, fully one-third of our

species lives in nations that are consciously attempting to build socialism,

and Marxian socialism is the dominant ideology of resistance in the remainder

of the world. It seems reasonable, therefore, to suspect that we are witnessing

a world historical event of the greatest significance for humanity: the end of

class rule and the emergence of a classless, world socialist society. The facts

that this transition is as yet incomplete, and that existing proletarian states

exhibit a variety of shortcomings, are not surprising when it is recalled that

capitalism was itself built through centuries of struggle, war, and revolution.

It is

frequently said that anthropologists should work in the interests of

"their" people (see, for example, Weaver 1973). It is also often

argued that these interests should be defined by the "natives"

themselves. In view of these feelings, it seems clear that anthropologists

should become more concerned with their new socialist order which is struggling

to be born. Just as the earlier misunderstanding and denigration of

"primitive" and "savage" peoples stimulated anthropological

research into alien life styles, so the present systematic misunderstanding and

denigration of Communist and revolutionary movements should stimulate

anthropological research to clarify the issues presently faced by our species.

Such research

should include studies of the efforts of contemporary proletarian states to

build socialism and of the struggles of oppressed peoples in the neocolonial

world to overthrow imperialism. Equally importantly, however, attention should

be devoted to the theoretical clarification of the idea of socialism itself.

Just what is this socialism which is so compelling an idea in the contemporary

world?

This paper

attempts to clarify the Marxian concept of socialism by placing it in a modern,

ecological idiom and viewing social evolution as a form of ecological

succession which will culminate in a world socialist system. Marxian analysis

has become increasingly fashionable in recent years, but the real appeal of

Marxism lies not only in its radical critique of the world the bourgeoisie

built, but more importantly in the manner in which it shows how the dialectic

of the capitalist present leads inexorably to the socialist future. Before

proceeding, let me make two points of clarification.

First,

socialism should be understood as a classless world social order in which the

means of production are socially owned and democratically managed to produce

for use rather than private profit.[1]

Clearly, existing proletarian states such as Russia and China, do not conform

to this conception, nor do the so-called "mixed economies." Socialism

does not exist at the present, except as an idea and a potentially inherent in

capitalism.

Secondly, if

socialism is indeed possible, this fact is of tremendous importance to every

member of our species. But this is a complex topic on which intelligent people

can honestly disagree, and discussion of this important topic must be based on

the greatest possible degree of freedom, with a full consideration of all

reasonable opinions. For if socialism is not possible, if it is simply an

ideological weapon used to deceive by a new group of predacious would-be

rulers, then this would also be of the greatest significance. I will of course

present my own views as forcefully and persuasively as possible.

This may appear

to be a form of special pleading, or it may appear to be doctrinaire and

visionary. If this is so, perhaps it will stimulate more intelligent discussion

of this important topic by voices more capable than my own.

Sociocultural

Systems in Ecological Perspective

It is useful to

adopt a natural history approach and view human societies as embedded in more

inclusive ecosystems, composed of matter, energy, and information (Odum 1971;

Richerson and McEvoy 1976). Ecosystems may be studied from a variety of

perspectives.

From a

synecological, or systemic, perspective, an ecosystem is composed of plant and

animal communities interacting with abiotic elements to maintain a flow of

energy through, and a cycling of matter within, the system. Within the

functioning of the total system, each species plays a distinctive role, its ecological

niche. All species

interact with, and influence, all the others, but this influence is not equal.

Frequently, one or a few species, the ecological dominants, will exert a major controlling influence

on the system as a whole. The ecosystem is kept in continual motion by the flow

of energy through the system. This motion, in turn, produces both stability and

change in the system itself. We may distinguish between change in the

components of the system, and change in the system itself.

Change within

the component species making up an ecosystem includes both developmental change

within the life cycle of the species in question, and evolutionary change. The

latter, genetic evolution, is a matter of change in the statistical frequency

of genetic information in the gene pool of the species, brought about by

mutation, natural selection, and drift.

Above the

species level, there are two sorts of changes. One, which we may call

ecosystemic evolution, results from the tendency, at the species level, to

occupy unoccupied niches. Since the advantages of occupying a previously

unoccupied niche are very great, natural selection favors those variations

which are best able to exploit the resources of the new niche. This alters the

selective pressures operating on the portion of the population which has occupied

the new niche, and this, in turn, leads to niche separation, specialization,

and speciation. The tendency toward complexity in the evolution of ecosystems,

then, is a logical concomitant of natural selection at the species level.

Another sort of

ecosystemic change is ecological succession, in which there are regular changes

in the makeup of the plant and animal communities composing an ecosystem. Such

ecological succession can be seen, for example, if one clears land in the

southeastern United States. The grasses which flourish in the first few years

are replaced by a mixed grass-shrub community which lasts for about twenty

years. Gradually, however, the competitive advantage which longer lived pine

trees have in an open, sunny environment leads to a pine forest community from

which the grasses and shrubs disappear. The pines, however, in achieving a

position of ecological dominance, themselves create the conditions under which

they can no longer reproduce, since the competitive advantage of pines in an

open environment is lost in the shade of the mature pines. Here, hardwoods such

as oak and hickory have a competitive advantage and as the first generation of

pine trees dies off, their place is taken by oak and hickory. Since the oak and

hickory can reproduce in their own shade, the oak history forest represents a

mature, stable system, an ecological climax which persists indefinitely unless altered

by geological or climatic change.

In addition to

the synecological study of ecosystems, it is also useful for anthropological

science to study ecosystems from an autecological framework, that is, from the

standpoint of a single species, in our case, Homo sapiens. Since human populations are almost

universally ecological dominants, such a study obviously has relevance for

understanding the system as a whole, as well. We may turn, then, to look at the

elements of an autecological framework for understanding human society, a

framework that not only sees society as embedded in the larger ecosystem, but

also attempts to see the internal features of human societies in ecological

terms.[2]

As noted above,

ecosystems are composed of three sorts of entities, matter, energy, and

information. The material entities include the human population and the environment. Within this environment, the human

population occupies a definite ecological niche. The ecological niche, viewed in

synecological terms, is the place of the population in the total functioning of

the ecosystem. From an autecological perspective, the ecological niche grows

out of the specific needs of the population, for certain kinds of food,

shelter, and so forth. The ecological niche, then, is made up of those

environmental features which the population requires to satisfy these needs.

Such environmental objects are use values, which, in human populations, is a rather broad category. The

concept of use value includes: (1) natural use values, such as air and water; (2) resources, things which are potentially use values

but which must be transformed into culturally acceptable use values through the

expenditure of human labor energy; (3) consumers' goods, use values which have been produced by

human labor and which are used directly to satisfy human needs; and (4) the means

of production, use values

which are not used directly to satisfy human needs, but are used in the process

of producing other use values. In addition to use values, the environment also

contains hazards,

anything which threatens the well-being of the members of the population.

Thermodynamic

entities include the bioenergy system, or the food energy resources upon which the population

depends, the ethnoenergy system,

or the manner in which human energy is expended in the satisfaction of the

needs of the members of the population, and the auxiliary energy system, or extra somatic energy (draft animals,

fossil fuels) which are used instrumentally by members of the population. These

material and thermodynamic entities, taken together, constitute the material

conditions of life.

The

informational sphere includes both genetic and learned information. Learned information may be acquired by situational

learning of individual

organisms, by social learning,

where information is transmitted between individuals, for example through

imitation, and by symbolic learning,

where information is transmitted through symbols (see Fried 1967:5-7). The

totality of non-genetic information, including modal personality, basic values,

world view, folk taxonomies, cognitive maps, kinship terminologies, behavioral

rules, and technological and social strategies, existing in the minds of all

the members of the population constitutes the cultural pool. The expression of this information in

verbal and other symbolic behavior constitutes the manifest cultural pool.

These various

components of human ecological systems are always inter acting, and in the

functioning of the system, there are a variety of cause and effect

relationships between the various components of the system. Although these

cannot be considered in any detail here, mention should be made of some of

them. First of all, information in the minds of members of the population is

the immediate cause of all human behavior, and thus controls the patterned

expenditure of energy by the members of the population. Second, there are cause

and effect relations within the material sphere of life, as human behavior has

a direct, material effect on the environment and on other members of the

population. Much of classical social science, especially classical political

economy, is concerned with these cause and effect relationships within human

populations, for example the supply and demand equilibrium model of classical

political economy or much of the analysis in Marx's Capital. Third, there are cause and effect

relations between the material conditions of life and information. These take

the form of selective pressures

(analogous to the material conditions of life, especially human behavior, which

favor selective pressures of the synthetic theory of bio-evolution) generated

by certain ideas over others and thereby control the statistical strength of

various ideas in the minds of the members of the population.

Human cultural

evolution exhibits many of the characteristics both of genetic evolution (in

that it involves statistical changes in the frequency of different sorts of

information in the cultural pool of the population), and due to niche filling).

of ecosystemic evolution (in that it involves expansion and increased

complexity The analogy I would like to pursue in the present discussion,

however, is that between human cultural evolution and ecological succession. To

do so, let me step back and look again at the processes of change in natural

(i.e., non-cultural) ecosystems.

As noted

earlier, the entire ecosystem, including its human component, is kept in motion

by the continual flow of energy through the system as green plants harness

solar energy, convert it into plant matter, which in turn is harnessed by

herbivores, who in turn are eaten by carnivores, and so on. The flow of energy

through the ecosystem, then, is effected by various organisms who eat, and are

eaten by, other organisms.

Life itself may

be viewed as a struggle for free energy, as a temporary reversal of the Second

Law of Thermodynamics, characterized by the incorporation of greater and

greater amounts of energy into more and more complex biological systems. In

this perspective, we may follow Lotka (1945) and see evolution as operating

according to a maximization principle, in which natural selection favors genes

which facilitate the harnessing of energy. Natural selection also favors genes

which contribute to greater efficiency in behavior or biological structure.

Combining these, we may see a minimaxing principle as a major explanatory

device in the understanding of biological evolution: within the synthetic

theory of bio-evolution, traits are explained by showing how they contribute to

more complete utilization of environmental energy resources and toward more

efficient use of available energy. The minimaxing tendencies of different

species may operate in opposite directions (wolves becoming more efficient

predators while deer becoming more efficient at escaping from wolves) or in

complementary directions, leading toward cooperation between species.

This

necessarily truncated discussion of the thermodynamic aspects of the

"struggle for existence" is intended less to shed light on biological

evolution than to introduce a thermodynamic conception of cultural evolution.

All animal populations are dependent upon the flow of bioenergy through the eco

system and also on the expenditure of their own ethnoenergy in efforts to

harness bioenergy, escape from predators, reproduce, and so on. Human

populations share this pan-animal dependence on bioenergetic flow and

ethnoenergetic expenditure, but human populations are also dependent upon a

particular form of ethno energetic expenditure, labor. All human populations

are dependent upon the expenditure of human labor energy into systems of

production that transform environmental resources into culturally acceptable

use values. We may speak of the labor energy expended in producing use values

as being embodied in these use values, and when the goods are consumed, we may

speak of the consumption of a definite amount of labor energy. It is important

to distinguish this deep flow of ethnoenergy, in which labor energy flows

through productive systems, into use values, and then back again into the human

population, from the surface flows in day-to-day activity. The latter may be

seen in all animal populations, the former is the defining characteristic of

humanity, for, as I have argued elsewhere, the unique characteristics of our

species, our bipedalism, our abilities to reason and converse, even our

religious capabilities, are all adaptations to a way of life based on social

production (Ruyle 1976). Several points about this deep structure of energy

flows need to be made.

First of all,

all human life, and all

human beings, are dependent upon this deep flow of energy. "Even when the

sensuous world is reduced to a minimum, to a stick," observed Marx and

Engels (1939:16), "it presupposes the action of producing the stick."

Further, few human beings produce more than a small percentage of the actual

use value they consume, and few consume more than a small percentage of the use

values they produce. This means that human production and consumption are

social activities, and that the deep structure of energy flow constitutes an

essential substratum of human social life which is lacking in the social life

of monkeys and apes. It is through this deep thermodynamic structure that human

beings satisfy their needs for food, clothing, shelter, and any other needs of

a material sort.

Now, just as

life itself may be viewed as a struggle for free bioenergy, so human life may

be viewed as a "struggle" for the labor ethnoenergy embodied in use

values. A major aspect of all human life is the withdrawal of social labor, as

embodied in use values, from the social product. Since use values, by

definition, satisfy human needs, and since for most of our species, basic needs

are not fully met, it follows that there is a general tendency to maximize

control over need satisfying use values, or, in thermodynamic terms, to

maximize control over the ethnoenergy that provides need-satisfaction. Further,

to the extent that expenditures of labor energy are not in themselves

satisfying, there will be a tendency to minimize ones own expenditure of labor

energy. Consequently, we may speak of a minimax principle in human behavior, such

that individuals tend to maximize their control over, or consumption of, labor

energy, and minimize their own expenditure of labor energy.

A few points of

clarification about this minimax tendency should be noted. First of all, the

idea of a minimax tendency does not depend upon the idea that human needs are

insatiable, for I believe this idea to be erroneous (cf. Mandel 1970:660-664).

All that is needed for the principle to be operative is a desire for a standard

of living ten percent higher than the existing one. Secondly, it is not assumed

that all human labor is inherently unsatisfying, for I believe that this idea

is also erroneous. Labor provides profound satisfaction to the human animal.

But again, all that is needed is a desire to reduce labor output by ten

percent, a reasonable enough assumption for most of human history. Third, all

members of the population need not exhibit the minimax tendency equally

strongly, for clearly there is individual variation in this as well as all

other personality characteristics. Fourth, in speaking of a

"struggle" for labor energy, I do not mean to imply that everyone is

a social imperialist, ruthlessly satisfying his own needs in opposition to all

others, for need satisfaction can usually be maximized by cooperation rather

than competition. Finally, it is not claimed that minimaxing explains

everything. I will indeed argue that the most significant aspects of cultural

evolution are inexplicable without reference to something like a minimaxing

principle, but this does not mean that I feel that minimaxing is the only principle in operation.

This concept of

a minimaxing principle underlying human behavior is quite similar to, if not

identical with, the concept of enlightened self interest of classical political

economy. Indeed, the concept of a deep structure of energy flow delineates an

area of inquiry roughly coterminous with that of political economy, which

"studies the social (inter-personal) relations of production and

distribution. What these relations are, how they change, and their place in the

totality of social relations" is the subject matter of both political

economy and ethnoenergetics (Sweezy 1968:3).

There are a

number of areas in which this minimax tendency has extremely important

consequences. First of all, it underlies the progressive development of the

forces of social production. There are two aspects to this development. First,

it is a movement toward greater efficiency; more use values can be produced per

unit of labor expended. Second, there is an emergent quality, in that new kinds

of use values can be produced.

Another

consequence of the minimax tendency is closely related to the first, and has to

do with the relations

of production. Clearly, the individual can maximize his own benefits by cooperation in production, which allows greater

efficiency and also allows more different kinds of things to be done, by the division

of labor, which permits

specialization and greater efficiency, and by reciprocity, the mutual sharing of the products of

labor. The result is the emergency of systems of mutual interdependence.

Participation in a system of social production is in accord with the

enlightened self-interest of the individual, because such participation enables

the individual to maximize his benefits and minimize his energy costs. In

speaking here of the "enlightened self-interest of the individual," I

do not mean to imply that each individual enters the system with a well formed

idea of what his "interests" are. This is obviously not the case.

People enter social systems as infants, unformed individuals who are molded by

society. Such molding, however, takes place within fairly narrow limits, limits

which approximate quite closely what an outside observer would call

"enlightened self-interest."

Another consequence

of the minimax tendency is the emergence of exploitation, and of a predatory

niche involving living by exploiting the labor of others. This requires some

explanation.

When people

expend energy in production, and consume energy in the form of use values, they

are doing more than interacting with the environment. They are interacting with

each other. The flow of labor energy from producer into use values and then

into consumers is a flow of energy from producers to consumers. Thermodynamic

analysis, therefore, provides a way of measuring quantitatively the social

relations of production and consumption. This may be done most parsimoniously

by simply measuring the amount of energy a given individual, group, or class

expends in production (E), and the amount of energy the same individual, group,

or class consumes in the form of use values (I). If the latter is more than the

former, we may speak of surplus (S = I - E). This surplus must come from

somewhere and, since no new energy is created by production, it can only come from other

members of the population. The surplus accruing to one part of the population,

therefore, must be extracted from other members of the population, where it

appears as a deficit, or negative surplus. The extraction of surplus is in

accord with the minimaxing tendency of those who receive the surplus, but it

runs counter to the minimaxing tendencies of those from whom the surplus is

extracted. On theoretical grounds, therefore, we would expect that the

differential flow of energy to the surplus extracting portion of the population

would be associated with conflict. And this is indeed the case. I know of no

case where an appreciable amount of surplus is extracted from a population

without the use of force by the surplus extracting population. In such

situations, therefore, we are justified in speaking of exploitation, which we may define as the forcible

extraction of surplus from a class of producers by a class of non-producers.

Earlier,

mention was made of the concept of ecological niche, or the manner in which a

given population is attached to the flow of energy through an ecosystem. It is

fruitful, I think, to extend this concept to classes within human populations,

and speak of a socio-ecological niche as the manner in which a given class is attached to the flow

of labor energy through the human ecological system. There are myriad different

possibilities, but it is important to recognize three fundamentally different

kinds of socio ecological niches. First, there is the basic producer niche, which involves expending energy into a

productive system and withdrawing an equivalent amount of energy in the form of

use values (E = I). Second, there is what we may call an exploiter niche (E < I), which involves extracting

energy from a productive system without a corresponding labor expenditure into

the system. Finally, there is the exploited producer niche (E> I), which involves expending energy

into a system and withdrawing less energy, the surplus going to a predacious

ruling class in the exploiter niche.

The basic

producer niche was, until about five or ten thousand years ago, the only niche

occupied by members of our species. It is now occupied by small populations of

hunters and gatherers and horticulturists on the geographical periphery of

civilization. The predator niche is occupied by ruling classes and their

retainers in historic and contemporary civilizations. The exploited producer

niche is occupied by peasants, serfs, and slaves in historic civilizations and

by workers in contemporary society.

We shall

examine the predator niche and its occupants in greater detail shortly. Certain

points may be made, however, at this time. The flow of energy to the ruling

class results from the efforts of the members of the ruling class who expend

energy not into the productive system but rather into an exploitative system

made up of definite exploitative techniques and definite institutions of

violence and thought control. This exploitative system, then, is for the ruling

class the functional equivalent of the productive system for a population of

basic producers; it is consciously manipulated by the rulers for their own

ends. These ends include a much higher return on energy expended in

exploitation than that expended in production by the direct producers, and a

much higher per capita consumption of labor energy for the exploiters. Movement

into the exploiter niche, then, is in accord with the minimaxing principle.[3]

Since the rulers are consciously manipulating the system for their own ends (although

they do not necessarily conceptualize this as exploitation) we are justified in

terming such a system as a system of class rule. However, the exploited

producing classes resist exploitation in various ways, so that class struggle

between exploiter and exploited is a ubiquitous feature of all systems of class

rule.

Sociocultural

Evolution as Ecological Succession

The operation

of the minimax principle, then, underlies the major trends in human cultural

evolution: the progressive development of society's productive forces and the

emergence of systems of exploitation and class struggle. The former of these

processes occurs in all social systems, although the strength varies in

different types of social structures. The latter is manifested only in particular

kinds of ecological situations, namely in large, dense populations of an

intermediate range of cultural development. Class rule does not appear among

hunters and gatherers, because the nature of the productive system has definite

barriers against the emergence of exploitation. Class rule will disappear in

the future when analogous barriers are erected against the continuation of

exploitation. This process of the emergence, development, and overthrow of

class rule forms the foundation for the succession of human ecological types,

each marked by distinctive productive systems, social structures, and

ideological features or complexes.

In broad

outline, we may distinguish four types of human ecosystems, corresponding to

the four epochs of human history: primitive communism, feudalism, the world

capitalist system, and the world socialist system.

The earliest

social order of our species was the primitive communism of the hunting and

gathering world, marked by an equal obligation of all to participate in social

labor, by a rough equality in consumption, and by unimpeded access to strategic

resources, to violence, and to the sacred and supernatural. Social order was

rooted in a common dependence on a system of social production. Primitive

communism endured, no doubt, for millions of years, and it was during these

millions of years of life within a primitive communist social order that

humanity evolved its present morphological and psychological nature

characteristics.

There is strong

resistance among anthropologists to the use of the term "primitive

communism" to refer to the egalitarian social orders of hunters and

gatherers, and, to the best of my knowledge, Leacock is about the only major

American anthropologist who is willing to use the term (1972). Several points

of clarification, then, need to be made concerning the concept.

First, the

adjective "primitive" in the sense of "original." This was

the original social order of our species, enduring as the only social order

from Australopithecine times to the emergence of the earliest systems of class

rule about 10,000 years ago.

Primitive

communism is primitive also in the sense of rudimentary and undeveloped. This

was by no means a perfect social order. The forces of social production were

weakly developed and life, while not quite "nasty, brutish, and

short" left much to be desired from the standpoint of such things as

infant mortality, life expectancy, and care of the sick and aged. Further,

although society was egalitarian in the sense that everyone had an equal

obligation to participate in social production and an equal claim on the social

product, there were also sex and age hierarchies marked by exploitation and

oppression. Further, although private property in the bourgeois sense did not

exist, and although there was unimpeded access to the strategic resources,

articles of consumption were owned as personal possessions.

Finally, the

primitive commune was not necessarily inhabited by "noble savages,"

although there was probably a higher incidence of human decency in primitive

communism than in later systems of class rule. Consequently, conflicts and

quarrels did occur, most typically between males over females (who were

important sources of labor). Conflict resolving mechanisms were not always

sufficient to keep these from erupting into violence. But this violence was

between equals, and not the one sided violence characteristic of class rule.

Balancing these negative features were positive ones. The gross in equalities

in conditions of life and in opportunities for self-development, the domination

of one person by another, repressive institutions such as prisons, police, the

State, and the Church which characterize later systems of class rule, were

lacking in primitive communism. Many writers have also remarked on the

"liberty, equality, and fraternity" of primitive communism, on the

high values placed on equality, sharing, freedom, and cooperation (Leacock

1972; Lee 1969; Diamond 1974; Morgan 1964; Lenski 1970).

Primitive

communism is a social order occurring typically among hunters and gatherers.

Although it also occurs among some horticulturists (Morgan's Iroquois, usually

seen as the type example of primitive communism, were already at the

horticulturist state), the Neolithic Revolution and the transition to food

production created conditions undermining the primitive communism of the

hunting and gathering world. The transition to horticulture was accompanied by

what Lenski called an "ethical regression," marked by an increased

incidence of warfare, inequality, headhunting, scalp-taking, cannibalism, and

other "barbaric" practices (1970:235-236).[4]

This, then, was

the era of the breaking-up of the primitive commune and the emergence of a new

social order, class rule. As populations became large and sedentary, the bonds

of interdependence that held together the primitive commune weakened, and a new

socioecological niche opened, that of predation.

In contrast to

the rough equality of consumption in primitive communism, stratified population

societies are marked by gross differentials in access to the social product.

The last five thousand years of human evolution have been characterized by the

existence of classes which, although their members do not directly participate

in a productive system through the expenditure of their own labor power, are

nevertheless abundantly provided with the good things of life. In all

class-structured societies, we know that those classes (slaves, serfs,

peasants, workers) that contribute the greatest amount of labor to the productive

system receive the least, while those (slavemasters, nobles, 1and lords,

capitalists) that contribute the least amount of labor receive the most. How do

we account for this peculiar situation?

Classes that

did not directly participate in production emerged simultaneous1y with special

instruments of violence and thought control that are staffed and/or controlled

by those who enjoy the newly emerging special privileges and wealth. From a

historical materialist standpoint it is essential that we regard the wealth and

privileges of certain classes as resulting from the activity of individuals. We

are inescapably led, then, to the conclusion that the differentials in wealth

and privileges of certain classes are a result of the efforts of those classes.

These efforts take the form of expenditures of energy in exploitative .systems

that pump economic surplus out of the direct producers and into the exploiting

classes that protect their resulting wealth and privileges.

Just as one can

see a definite system of production supporting any human population, so,

wherever one sees gross inequalities in standards of living and wealth, one can

also see a definite system of exploitation controlled by those enjoying the

highest standard of living and the greatest wealth. Systems of exploitation are

as variable as systems of production, but all share certain features. There

are, first the exploitative techniques, the precise instrumentalities through which economic surplus

is pumped out of the direct producers: slavery, plunder, tribute, rent,

taxation, usury, and various forms of unequal exchange. Second, there is the State, an organization which monopolizes

violence and is thereby able to physically coerce the exploited population.

Third, there is the Church,

an organization which controls access to the sacred and supernatural and is

thereby able to control the minds of the exploited population. These elements

of the exploitative system may be institutionalized separately, as in

industrial societies such as the United States and the Soviet Union, or they

may be integrated into a single unitary institution, as in the early Bronze

Age. The precise ensemble of exploitative techniques, together with the manner

in which State-Church elements are institutionalized, constitutes a historical mode

of exploitation.

The State and

the Church, then, form twin agencies of oppression and thought control whose

purpose is to support and legitimate the exploitation supporting the ruling

class. But in addition to their repressive role, these agencies also carry out

a variety of socially beneficial governmental functions.[5]

Generally

speaking, the State carries on the following functions in developed class

societies: waging war, suppressing class struggle, protecting private property,

punishment of theft, constructing and maintaining irrigation works, state

monopolies of key economic resources, regulation of markets, standardization of

weights and measures, coinage of money, maintaining roads and controlling

education.

The Church is

often viewed as a religious institution, but it is also an important agency of

social control. The State subdues the bodies of human beings, the Church their

souls.[6]

White (1959:323-328) provides abundant documentation of the role of the Church

in subduing the souls of human beings by (1) supporting the state in war, in

suppressing class struggle and protecting private property, and (2)

"keeping the subordinate class at home obedient and docile."

The Church,

then, plays a very important role in legitimating the system by showing the

social order to be an extension of or in accordance with the natural and sacred

orders. This legitimation has a dual aspect. First, of course, there is the

manipulative, thought control aspect in which the content of religious ideology

is consciously shaped in order to support the system. Second, and also very

important, is the legitimation of the system to the rulers themselves.

The

exploitative system is the instrumentality through which a predator prey

relationship is established within the human species, only here the stakes are

human labor energy rather than energy locked up in animal flesh. The

differentials of wealth and prestige which emerge from this predatory

relationship simultaneously reflect and legitimize the differential consumption

of labor energy by predator and prey. Once the predatory relationship is

established, the system of exploitation supporting it becomes larger and more

complex, with a complex division of labor deve1oping in both the sphere of

production (between agricultural workers and workers in the industrial arts,

metallurgy, textiles, pottery, and so forth) and in the sphere of exploitation

(warriors, priests, scribes, etc.). The result is an elaboration of occupations

and statuses among different kinds of producers, exploiters, parasitic groups,

and so on. This predatory relationship generates a division of the population

into classes, which are defined by their relationship to the underlying flow of

labor energy through the population.

The

exploitative system supporting a predatory ruling class fulfills the same

function vis-a-vis the ruling class that the productive system fulfills for a

band of hunters and gatherers, that is, it is consciously manipulated in order

to provide them with the use values essential for human life. It does so,

however, on a scale far surpassing anything in the hunting and gathering world.

Once

established, this exploitative system follows its own evolutionary trajectory,

governed by a number of forces. First of all, because of the minimax tendency,

it tends to become more efficient at extracting surplus, and tends to become

larger and capable of extracting more surplus from a larger population. This

tendency runs parallel and complementary to the progressive development of the underlying

productive system, a development to which the exploitative system must be

adapted. However, the development of production occurs within the constraints

of the system of class rule, so that the relationship between the mode of

production and the mode of exploitation is a dialectical one.

Another

important force underlying the evolution of systems of class rule is class

struggle. Exploitative operates not on nature, but on human beings. Therefore,

it generates resistance. This resistance on the part of the direct producers is

in accord with the minimax principle discussed above, and takes a variety of

forms, ranging from flight, concealment of production, and petty thievery to

organized armed resistance.

Further, the

predator niche is attractive to groups outside the system, and nomadic hunters,

such as the Aztecs, or nomadic herders, such as the Mongols, pose a continual

threat to the occupants of the predator niche. The predator niche, then, is by

its very nature, a precarious one.

**************************************************************

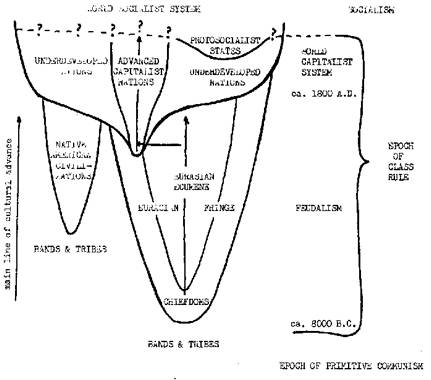

Figure 1.

Evolutionary Taxonomy of

Sociocultural Systems.

**************************************************************

Under the

influence of these selective forces, the exploitative system supporting a

ruling class undergoes a more or less regular succession, as small, weak

systems are replaced by larger, stronger ones. The details of the evolutionary

history of class rule need not be discussed in any detail here, but some of the

major features are diagrammed in Figure 1. The main line of cultural

development, down to about 1500 A.D., runs through the historic civilizations

of what Kroeber called the Eurasian oikoumene (1945). McNeil has noted several phases in

the development of the oikoumene,

or ecumene, an era of Middle Eastern dominance to 500 B.C., an era of Eurasian

cultural balance between the Mediterranean, the Middle East, India, and China

from 500 B.C. to 1500 A.D., and the era of Western dominance after 1500 A.D.

(1965). In addition, there are peripheral forms: medieval Europe, subSaharan

Africa, Southeast Asia and Indonesia, Oceania, and Japan, and a later,

parallel, evolutionary development in the New World.

These various

precapita1ist forms of class rule may be lumped together

under the category

of feudalism, for they share certain characteristics which distinguish them, as

a social type, from capitalism.[7]

These characteristics include, first of all, the exploitative techniques, which

include plunder, slavery, serfdom, usury, and mercantile activity, but do not

include in any important way, industrial wage labor. Systems of exploitation

based on these techniques lack the inherent instability of industrial

capitalism, as will be discussed below. Secondly, the ideological systems

legitimating feudal rule are also stable, in that the hegemony of the Church is

unchallenged, the dominant value is hierarchy, not equality, and no viable

alternative to the system exists, even in thought. As a result, class struggle

is within the system, directed toward the elimination of excessive abuses, such

as removing unjust rulers or gaining tax relief, and not directed against the

system of class rule itself.

The various

feudal forms of class rule, then, are not inherently unstable, although there

are extra-systemic sources of instability. The ruling classes of feudal

societies, however, themselves created the conditions under which they could no

longer endure. In establishing stable social orders and in fostering the

development of the productive forces of society, the feudal rulers paved the

way for a new ruling class, the bourgeoisie, which, as the Communist Manifesto

notes, "has played a most revolutionary role in history" (Marx and

Engels 1964:5). This new ruling class has created a radically new social order,

and for the first time, brought the entire world together in a single

ecosystem.

We must ask,

however, whether this ecologcial succession goes on forever, or is there an end

in sight, a mature stable human ecological climax? Is bourgeois society itself

such a climax? Are we living at the oak-hickory stage of human evolution, or

simply in a pine forest? Perhaps humanity will degrade its own environment and

retrogress to a more primitive state, or perhaps even become extinct?

These are

weighty questions which cannot be approached in a dogmatic spirit. Neither can

they be intelligently discussed without taking into account the analysis made

by Marx a century ago. According to this analysis, the new bourgeois world

order, unlike the earlier feudal orders it replaced, is a highly unstable

system, rent by powerful contradictions of both a material and an ideological

nature. Let us examine some of the more important of these.

Capitalism:

The Marxian Analysis

Marx's analysis

of capitalism is one of the towering achievements of humanity, for Marx laid

bare the laws of motion of capitalism and showed how capitalism, as a system of

exploitation, generates the social ills which plague bourgeois society:

unemployment, poverty, crime, and racism. It is obviously impossible to examine

Marx's analysis in any concrete detail, but it may be useful to review some

aspects of the analysis in an abstract way (for an introduction to Marx's

analysis, see Sweezy 1968), and show how it articulates with the ecological

view of social evolution.

Marx's analytic

tool, the labor theory of value, fits in well with the ecological framework

developed above, for value, in Marx's analysis, is a thermodynamic concept: the

amount of socially necessary labor embodied in a commodity. Marxian value

analysis, then, represents an ethnoenergetic analysis of capitalism which

examines the flows of energy between classes in the process of production and

exploitation.

These

thermodynamic flows can be seen in Marx's formula for capitalist production, M

- C1 + C2 . . . C' - M', in which the capitalist begins with money (M),

exchanges this for two sorts of commodities, raw materials and the-means of

production (C1)' and labor power (C2)' combines these in the labor process to

produce new commodities (C'), which he then sells for money (M'). This formula

serves to draw attention to certain essential features of capitalism. First of

all, the profit motive. Since the capitalist begins and ends with money, the

sole rationale for this circulation of money is that the second sum of money

(M') must be larger than the first (M). This increment of money (M = M' - M) is

profit, a form of surplus value, the sole motive force of capitalist

production. This makes capitalism quite different from all other productive systems,

for profit is an economic category specific to capitalism. In primitive

communism or feudalism, production is controlled by the producers themselves in

order to produce use values essential for existence; profit simply does not

appear as part of the system. In capitalism, production is controlled by the

capitalist class for the purpose of producing profit for the capitalist. The

production of use values is only a means of attaining this end. Secondly, the

secret of capitalist exploitation. Profit, or surplus value, is a thermodynamic

entity, a definite amount of congealed human labor. Energy, however, flows

through socioeconomic systems but is not created by them. The energy embodied

in profit, therefore, must ultimately come from human labor power. Capitalist

profits may come either

from selling commodities above their value (thus exploiting the buyer) or

buying commodities below their value (thus exploiting the seller). The strength

of Marx's analysis, however, is that he showed that capitalist exploitation

does not depend on

either of these, that it can occur even when all commodities are exchanging at

their proper value. The secret of capitalist exploitation, for Marx, lies in

the peculiar nature of one of the commodities purchased by the capitalist,

labor power.

Like all other

commodities, labor power has both value and use value. Its value is the amount

of socially necessary labor required to produce the goods upon which the worker

and his family subsist, say twenty hours per week. The use value of labor power

is its ability to labor, to not only reproduce the goods it contains, but to

continue producing for a full work week, say forty hours. It is this

differential between the value and the use value of labor power which is the

source of profit in capitalist production.

Looking at this

in terms of Our earlier discussion of energy flows, we see that the worker's

income (I) is twenty hours per week, his output (E) is forty hours per week, so

that twenty hours of surplus (S = I - E = 20 = 40 - 20) is being extracted from

the worker each week. This surplus belongs to the capitalist since it was

produced by his property, the worker's labor power, and this is the source of

profit in capitalist production.

Capitalism,

then, like feudalism, is a system of exploitation designed to extract economic

surplus from the direct producers. The specific exploitative technique in

capita1ism, wage labor, has extremely important systemic ramifications which

make capitalism strikingly different from feudalism.

Capitalist

production presupposes a basic two class division of society between the

capitalist class, Or bourgeoisie, who own the means of production and live from

property income, and the working class, or proletariat. who do not own any

productive property and therefore must live from the sale of their labor power.

The worker is politically and legally free, but economically he is in bondage,

a wage slave. Lacking independent access to the means of production. he is

compelled to sell his labor power on the labor market for whatever price it

will bring and under whatever conditions may prevail. In order for the system

to operate efficiently (efficiently, that is, from the standpoint of producing

profits), it is necessary that there be an over supply of labor power, for this

ensures that the terms of the sale of labor power will be favorable to the

buyer rather than the seller. Unemployment, then, or what Marx called the

Industrial Reserve Army, is a functional necessity for capitalism, for it keeps

wages low, enforces labor discipline, and creates feelings of gratitude and

dependence within the class of employed workers, who see their employers as

benefactors providing them with a livelihood, rather than as exploiters.

Saying that

unemployment is necessary to capitalism does not, of course, explain

unemployment. The explanation of unemployment lies in systemic mechanists

within capitalism which serve to maintain unemployment. As unemployment is

reduced, and as wages therefore rise, decisive feedback mechanisms come into

play which serve to recreate unemployment.

First, there is

the introduction of labor saving machinery. As wages rise, employers have a

greater incentive to introduce new machines to cut their wage bill. This in

turn reduces the demand for labor, and helps recreate the Industrial Reserve

Army. Second, increased wages tends to attract workers from outside the system,

thereby increasing the supply of labor. Finally, and decisively, there is the

capitalist crisis. As wages rise, profits, in the last analysis. must fall. As

profits fall, capitalists stop investing and hold their capital in money form

to await better business conditions. ~t if capitalists don't invest, production

stops, and workers are thrown out of work, thus replenishing the Industrial Reserve

Army, lowering wages, and improving business conditions. Capitalism, thus has

built-in systemic mechanisms which ensure that there will be an oversupply of

labor, and that, therefore, the terms of sale of labor power will be favorable

to capitalist exploitation.

Unemployment,

then, is an essential part of the capitalist system, and with unemployment,

poverty, crime, and racial and ethnic antagonisms, growing out of the

competition for jobs within the system.[8]

Similar sorts of social problems also characterize other systems of class rule,

but in other systems they are likely to be symptoms of malfunctioning of the

system, not products of the normal working of the system.

Another

contradiction within capitalism is that between the tremendous growth in the

forces of production and the constriction of the ability of society to consume.

Already in

1848, before the development of automobiles, airplanes, automation, computers,

and interplanetary exploration, Marx and Engels (1964: 10) noted that,

"The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created

more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding

generations together.” This tremendous development of the productive forces of

society has eliminated the scarcity basis of class rule. No longer does one

class have to exploit another in order to enjoy the economic basis for a secure

and abundant life.

Yet at the same

time that capitalism develops society's productive forces, it simultaneously

restricts the power of the masses of workers to consume. The working class does

not receive enough money in wages to buy back the commodities it produces. The

economic problem in mature capitalism is thus transformed from one of scarcity

to one of overabundance: the worker finds that there is too much labor, not too

little, and the result is unemployment and poverty; the farmer finds that he

produces more food than he can sell, and has to be paid not to produce, even

when millions arc malnourished; the manufacturer similarly has no problem in

producing, but only in selling. This contradiction between the constant

expansion of society's forces of production and the constant constriction of

society's ability to consume generates a powerful tendency toward stagnation in

all systems of capitalist production.

But the

bourgeoisie produces something more than commodities, some thing more, even,

than contradictions. "What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above

all," according to the Manifesto, "are its own grave-diggers,” the proletariat (Marx and

Engels 1964:24). By breaking down the rural isolation of the peasant community

and the individual homesteader, by bringing the direct producers together into

cities and organizing them in larger and larger productive networks, by

compelling the workers to organize themselves in self-defense against the most

brutal exploitation, the bourgeoisie creates the force which is destined to

change the world, the proletariat.

Before the

proletariat can accomplish its historic mission, however, it must become conscious of this mission. But how is this possible?

"The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas: i.e.,

the class, which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time

its ruling intellectual force" (Marx and Engels 1939:39). Given the

hegemony of bourgeois ideology, how can the proletariat become conscious of its

own revolutionary powers? The answer lies in the nature of bourgeois ideology

itself. For this ideology is a product not just of bourgeois rule, but more

importantly of the historical conditions under which the bourgeoisie

established their rule.

We must recall

that the bourgeoisie is a revolutionary class which grew to maturity in

opposition to feudal exploitation and oppression. As the bourgeoisie rose to

the position of ruling class, it created decisive changes in consciousness and

political organization which could not be turned off when they were not longer

needed, but continued in opposition to bourgeois rule itself.[9]

The revolutionary bourgeoisie, in other words, created a revolutionary ideology

which legitimizes not bourgeois rule but proletarian revolution. There are

several considerations here.

First, the

development of a rational, critical social science provided the bourgeoisie

with the ideological weapon to attack feudal privilege and irrationality. But

as the bourgeoisie becomes a ruling class it no longer needs a materialist,

critical ideology, and bourgeois ideology becomes increasingly idealistic and

apologetic. Yet, once created, critical social science becomes a material force

in its own right, and does not stop with the attack on feudalism, but goes on

to attack bourgeois privilege and bourgeois rationality and irrationality as

well.[10]

Secondly, the

establishment of the institutions of parliamentary democracy enable the

bourgeois to rule with the consent and participation of other, non-ruling

classes.[11]

But by legitimating bourgeois rule in terms of popular consent, bourgeois

ideology also legitimates efforts on the part of the people to change the

system.

Third, there

are the basic values placed on freedom and equality. These were used to

legitimate the struggle to overthrow feudalism. They continue as basic values

legitimating bourgeois rule, even though they de-legitimate the unfreedom and

inequality which are necessary concomitants of that rule.

Finally, the

bourgeoisie raise expectations which cannot be fulfilled within the framework

of bourgeois society. Consequently, capitalism generates its own ideological

negation, the idea of socialism as a fulfillment of the promises made by the

revolutionary bourgeoisie.

The above

discussion of capitalism has been at a rather high level of ' abstraction,

dealing with the capitalist system, qua system. It is important to realize,

however, that the actual working out of the system on the ground involves a

number of complexities which cannot be discussed here. One important point

which must be made, though, is that capitalism is not a national but an

international, world system.

Some scholars

see the contemporary world as divided between advanced, "modern"

societies which have been transformed by the Industrial Revolution, and

underdeveloped, "premodern" societies which have not as yet been so

transformed. Such a view, however, ignores the most elementary facts of the

past five hundred years of world history. The Industrial Revolution, although

it occurred in Western Europe, was a world-historical phenomenon, and not just

a European one. As Marx (l967) showed in his chapters on the primitive accumulation

of capital, the capital which financed the Industrial Revolution came from the

plunder of the non-Western world. This process certainly led to the

transformation of social structures in the industrialized, Euro-American world,

but it also led to the transformation of social structures in the non-Western

world, as well. Through the process of what Frank (1966) called "the

development of underdevelopment," the social structures of the non-Western

world were rearranged to facilitate the extraction of economic surplus by the

advanced nations. The result was the emergence of two kinds of modern society

(or more properly, two kinds of subsystems within the larger capitalist world

system), both equidistant from the feudal societies that preceded them: advanced

capitalist nations, and underdeveloped nations.

Advanced

capitalist nations are characterized by the presence of advanced industrial

plants and advanced technology. The economic surplus takes the form, primarily,

of profit, extracted from the working class through wage labor, but rent and

interest are also important exploitative techniques. The class structure

conforms to the classic Marxian two-class model: (l) a small, wealthy, ruling

bourgeoisie which lives on income generated by property' owner ship, which

controls production for its own profit, and controls the nation state and key

opinion forming institutions; (2) a working class, Or proletariat, that lives

on income derived from the sale of their labor power. Again, this description

is highly abstract, and does not include all the complexities of class

structure, but the reality of this structure is not negated by the existence of

gradations either within the classes or between them. The conformity of the

American class structure to the Marxian model will be touched upon below.

Within the

underdeveloped society, social relations are likely to appear feudal, and

indigenous ruling classes are likely to rely on "precapitalist" modes

of exploitation. The diagnostic feature of these social systems, however, is

the penetration of the advanced capitalist exploitative system into the

underdeveloped nation and the extraction therefrom of economic surplus in the

form of profits and unequal trade relations. It is this feature which locks

advanced and underdeveloped nations into a single, worldwide economic system.

Both advanced

capitalist and underdeveloped societies, then, are social types within the

world capitalist system, a highly unstable system marked by profound

contradictions between its advanced and underdeveloped parts, as well as the

material and ideological contradictions of capitalism itself, as discussed

above. Most importantly, with the development of the idea of socialism, the

continued existence of class rule can no longer be taken for granted, and class

struggle, in underdeveloped nations as well as advanced nations, enters a new

phase, toward the overthrow of class rule itself, and the building of a

classless, socialist world order.

Like feudalism,

then, capitalism is a system of class rule, but it is distinguished from

feudalism by the facts that it is a world wide system, incorporating all of

humanity into a single productive network, and that it is a highly unstable

system, rent by powerful contradictions.

The material

contradictions within capitalism do not mean, ipso facto, that capitalism will

collapse and socialism will emerge. Capitalism is a system of class rule,

consciously manipulated by a group of human beings, the bourgeoisie, who have

tremendous intellectual and material resources at their disposal to cope with

the problems generated by the system and to prevent its collapse. For all its

problems, then, the collapse of capitalism is not immanent.

The Marxian

model, however, is a two class model. Although the bourgeoisie can possibly

prevent the collapse of capitalism, they cannot prevent its overthrow. As the

proletariat becomes aware of itself as a class, and of its distinct interests,

vis-ą-vis the bourgeoisie, in building a more rational, humane world, it will

shake off bourgeois rule and emerge as a ruling class. The real forces which

are destroying bourgeois rule are not simply the material contradictions of

capitalism, but more importantly the forces which are bringing the proletariat

to an awareness of itself and its interests: critical social science,

democratic institutions, the values of freedom and equality, and the idea of

socialism.

When the

proletariat becomes a ruling class, it will establish its conditions of

existence as the ruling conditions of society, as have all previous ruling

classes. But since the conditions of life of the working class consist in its

obligation to labor and its lack of special privileges, a working class

revolution must abolish all special privileges and confer upon all an equal

obligation to labor. The classless society of the future wi11 build upon and

perfect the positive achievements of the bourgeoisie--the high development of

societies productive forces, bourgeois political freedom, and bourgeois

democracy.[12] But these

will be raised to new heights.

As the

politico-economic basis of class rule is abolished, social evolution will

return to its starting point. Class rule, the negation of the liberty.

equality, and fraternity of primitive communism, will negate itself in

socialism. At this point, the motive force of historical change, class

struggle, will have been eliminated and humanity will be in harmony with itself

and with nature.[13] This will

be a human ecological climax in which the major adjustment to the now

evolutionary force, human intelligence, will have been made, and the human

ecosystem will have attained a position of maturity and stability.

Socialism

as a Human Ecological Climax

In the

ecological interpretation of social evolution presented above, both primitive

communism and class rule were explained in terms of a single causal mechanism:

enlightened self-interest, or the minimax tendency. This basic mechanism,

operating in the material conditions of the hunting and gathering world, led to

a primitive communal social order. In the changed conditions after the

development of large, sedentary, agrarian populations, the minimax tendency led

to the emergence and evolution of progressively larger and more powerful

systems of class rule. What, then, are the changed conditions in the contemporary

industrial world that will lead to the end of class rule and the elimination of

exploitation?

It is not in

the interest of any majority to be exploited, and since the proletariat forms

the majority of industrial society, it is clearly in its interests to prevent

itself from being exploited. But, it Day be objected, is it not in the interest

of the majority to exploit minorities? The answer if equally clear. No, for the

benefits accruing from such exploitation would be too slight to justify the costs.

These include not only the cost of repressing the resistance of the minority

being exploited, but also of repressing dissident members of the majority. What

might happen is that a minority within the majority might attempt to exploit a

minority, but the majority would not benefit from this, and further, this would

pose a threat to the majority itself, since the exploitative system used to

exploit the minority could. in time, be turned against the majority. Similarly,

the workers of one country would not benefit from exploiting the workers of

another country.

The class

interests of the proletariat, then, lie in the elimination of all exploitation.

But the same could be said of a peasantry. Since the peasantry in feudal,

agrarian society was not able to end exploitation, what are the special

characteristics of the proletariat in industrial society which wi11 enable it

to enforce its class interest and build a non-exploitative, socialist society?

According to

Marxian theory, one of the important differences between a peasantry and a

proletariat lies in the nature of their respective productive systems. The

agrarian production of peasants is such that individual families can form

productive units. A peasant revolution, therefore, merely aids at redistribution

of private property rights in land. But such petty property in land merely lays

the groundwork for the reemergence of class differentiation in the countryside,

between rich and poor peasants. and, ultimately, between landlord and tenant.

Thus, although the long range, objective interests of the peasants may lie in

socialization of land and production, their immediate, perceived interests lie

in obtaining private property rights in land. But such petty private property

is impossible in industrial production. The worker cannot demand that ten feet

of the passably line become "his" property. The social character of

production demands social, not private, ownership of the means of production.

Thus, whereas a peasant revolution leads to a resurgence of petty private

property, a proletarian revolution leads to social ownership of the means of

production and to socialism.

Further, there

are important differences in the character of social life between a rural

peasantry in feudalism and the urban proletariat in capitalism. The proletariat

lives in a highly urbanized society and has access through mass communication,

to advanced critiques of the system, to the most advanced ideas of social

reform and revolution, and to the idea of socialism. These characteristics do

not apply to the typical peasantry of feudal society, although they are

increasingly characteristic of peasants in underdeveloped nations, who are

thereby becoming increasingly a revolutionary force.

As discussed

above, the forces which are undermining capitalism are the very forces which

will aid the proletariat in building socialism. The freedom of thought,

critical social science, and free press which provide the proletariat with an

understanding of the shortcomings of capitalism will also enable the

proletariat to discover abuses within the emerging socialist system. The free

elections and democratic institutions which give the proletariat the power to

overthrow capitalism also give it the power to eliminate these abuses as they

are discovered. Finally, the basic values of freedom, equality, and social

responsibility will reinforce the liberty, equality, and fraternity of world

socialism. This is not to say that there will be no conflicts or problems in

the building of socialism, only that these will not be insurmountable.

These

conditions, which are developed by bourgeois society, are either non-existent

or present in only rudimentary form in the precapitalist world.

What, then, are

the social conditions which will prevai1 in the socialist world order? To

begin, the forces of social production will be highly developed, and the

material base will exist for an abundant life for everyone. There will be a

roughly equal obligation for everyone to participate in the system of social

production, and everyone will enjoy roughly equal levels of consumption. This

is not to say, however, that there will be absolute equality or sameness.

Private property in articles of consumption (housing, clothing, books, leisure

articles) will continue under socialism, so that individuals may freely decide

for themselves what sort of life style and level of consumption they desire.

One person may wish to reduce his hours of labor to the minimum, say, ten hours

per week, and live in relative poverty so that he may devote himself to writing

poetry, while another may desire to increase his hours of work to thirty,

forty, or even fifty, so that he may enjoy a higher level of consumption. Such

differentials in labor expenditure and consumption are not exploitative and are

fully compatible with socialism. One should say, they are necessary for

socialism, for they are essential for the free development of each individual's

potential.

The above

description of the world socialist system may appear quite utopian, especially

since the average anthropologist, being a product of American culture, has a

number of built-in defenses against the concept of socialism. It is impossible

here to de-program these defenses in order to encourage a more objective

evaluation of the feasibility of socialism, but it may be useful to discuss two

of the most common objections to the theory of socialism. On the one hand.

where the working class has indeed made a revolution by placing a Marxist party

in power, the results have been, to many, disastrous. For many on the New Left,

"the Soviet Union is the most discouraging fact in the political

world" (Lynd 1967:29). On the other hand, the reforms of the New Deal and

Welfare Statism have, in the eyes of many, overcome the contradictions of

capitalist society, so that 20th century America is frequently seen as

"post-capitalist" or even "post-Marxist."

In order to

understand the contradictory nature of the social order of socialist bloc

nations, it is necessary to draw upon Trotsky's conception of the Soviet Union

as a "degenerated workers' state" (see Trotsky 1972; Duetscher 1967).

When the Bolsheviks were put in power by the Russian working class in the

October Revolution of November, 1917, they faced problems which were not fully

anticipated by Marx. First, the revolution took place in a backward rather than

an advanced nation, so that the material base of socialism had not yet been

built. Second, although the Russian working class was highly advanced and

politically conscious, it was numerically quite small in proportion to the

peasantry. Finally, the Russian revolution was immediately confronted with

foreign intervention, leading to a long and devastating civil war. As a result

of these particular historical circum stances, the working class destroyed

itself in protecting the revolution, and the Bolshevik Party was left as a

working class party without a working class. They had to act in the name of the

working class in building socialism, but without a working class to keep them

honest.

The continuing

functional needs to extract surplus from the peasantry to invest in an

industrial plant, and to protect the revolution from foreign intervention led

to a despotic state organization.

The

international communist movement came under control of the Russian Communist Party,

and the various national Communist Parties were built as instruments of Russian

foreign policy. As revolutions occurred elsewhere in the underdeveloped world,

they had to come under the control of the Soviet Union in order to remain

viable in the face of capitalist hostility. The result was the emergence of a

pseudo-socialist Soviet "imperialism."

Trotsky's

analysis, with suitable modifications, can be applied equally well to other

societies, such as China and Cuba, where socialist revolutions have occurred in

the context of underdevelopment. These societies should properly be seen as protosocialist

states, part of a world

transition to socialism but unable, on their own, to complete the transition

until the advanced capitalist nations join them. Protosocialist states, then,

are "socialist" to about the same extent that the advanced capitalist

nations are "democratic." Both systems are contradictory, living up

to their promises in some respects, sorely deficient in others. Marxism can

point with pride to the very real achievements of the Soviet Union, for

example, in economic growth, but need not take the blame for the very real

shortcomings which resulted from particular historical circumstances. A

worker's revolution in the United States will not face the same insurmountable

problems faced by the Russian workers in 1917. It is reasonable to suspect,

therefore, that when socialism comes to America it will be a more humane and

happier socialism.

A number of

scholars have argued that, although Marx's critique of 19th century capitalism

contained a good deal of truth, capitalism has changed since Marx's time and

these changes have had the effect of overcoming the contradictions of