ON THE ORIGIN OF PATRIARCHY AND CLASS RULE (AKA

CIVILIZATION)

By

Eugene E. Ruyle

Department of Anthropology

California State University, Long Beach

Long Beach, CA 90814

(213) 498-5171

Abstract

Recent research on the

origin of the state has shed useful light on the processes of state formation,

moving from the search for "prime movers" to the elaboration of

"systems" with "multivariate causality." In the process,

the insights of Marx and Engels on the class nature of the state have been

ignored. This paper proposes a thermodynamic model of class society which

attempts to incorporate both 19th century insight and 20th century data into a

unified theory of class and gender inequality. The proposed model sees

inequality as the consequence of the activities of ruling class men. With the

progressive development of the forces of social production and the growth of

population, predatory males devise ways of exploiting first women, and then

men. As the systems of exploitation grow, they support ruling classes that live

from the surplus extracted from the direct producers.

CONTENTS

The Transition from Primitive Communism to

Patriarchal Class Rule

AUTHOR’S NOTE, 2007: This

is the text of my article written in the early 1980s. Aside from correcting

some spelling errors and reformatting for the web no changes have been made.

The most significant change I would make if I were to re-write it would be to

change the term “primitive communism” to “ancestral communism” since I believe

the former term is pejorative and does not properly honor our ancestors.

ON THE

ORIGIN OF PATRIARCHY AND CLASS RULE (AKA CIVILIZATION)

The state, therefore, has not existed from all eternity.

There have been societies which have managed without it, which had no notion of

the state or state power. At a definite stage of economic development, which

necessarily involved the cleavage of society into classes, the state became a

necessity because of this cleavage. We are now rapidly approaching a stage in

the development of production at which the existence of these classes has not

only ceased to be a necessity but becomes a positive hindrance to production.

They will fall as inevitably as they once arose. The state inevitably falls

with them. The society which organizes production anew on the basis of free and

equal association of the producers will put the whole state machinery where it

will then belong - into the museum of antiquities, next to the spinning wheel

and the bronze ax (Engels 1972:232).

We no longer, however,

can be sure that there will be any museum of antiquities after the state

completes its career. Even leaving aside the possibility of the extinction of

our species in a "nuclear winter" (Sagan 1985), the growth of the

machinery of repression (Chomsky and Herman 1979) has reached a point that it

may seem foolhardy to look forward to future in which, once again, there will

be "no soldiers, no gendarmes or police, no nobles, kings, regents,

prefects, or judges, no prisons, or lawsuits" (Engels 1972:159). Yet in

such a future lies the sole hope for humanity. For this reason, if no other, we

must examine, dispassionately and without prejudice, the origins of this

institution which threatens our very existence.[1]

Recent research on the

origins of the state has illuminated the ecological conditions, productive

processes, and settlement patterns within which the earliest states developed.

Modern anthropological thinking has moved from the search for "prime

movers" such as conquest, irrigation, trade, environmental

circumscription, and religion, to "systems analysis" and

"multivariate causality" (Flannery 1972, Service 1975, Wright 1977,

Cohen and Service 1978, Classen and Skalnik 1978). Current thinking on state

origins focus on changes in ecological, demographic, and subsistence patterns

within relatively narrow time-frames (around 3500 B.C. in southwest Asia,

2000-1500 B.C. in north China, and 500 B.C.- 500 A.D. in the New World),

centering on the emergence of new authority patterns associated with the growth

of redistributive networks. While this is more precise than Engels, it is less

satisfying. Modern theorists, for all their sophisticated data, give little

indication that they understand what they are looking for.[2]

Just as pre-Copernican

astronomy could predict eclipses and chart with great precision the movement of

the planets without understanding the actual structure and laws of motion of

the solar system, so bourgeois anthropology can tell us with considerable

precision when and under what conditions the earliest states developed without

having the slightest inkling of the inner structure and laws of motion of the civilizational

process.[3]

For this, we need a Copernicus.

Fortunately, the social

sciences have already had their Copernicus and Galileo, but have willfully

denied them as surely as the Catholic Church denied these revolutionary

thinkers. The founders of historical materialism saw the modern state as

"but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole

bourgeoisie" (Marx and Engels 1978:475).[4]

This conception of the state as an instrument of class rule was further

elaborated by Engels:

As the state arose from the need to keep class antagonisms in

check, but also arose in the thick of the fight between the classes, it is

normally the state of the most powerful, economically dominant class, which by

its means becomes also the politically dominant class and so acquires new means

of holding down and exploiting the oppressed class. The ancient state was,

above all, the state of the slave owners for holding down the slaves, just as

the feudal state was the organ of the nobility for holding down the peasant serfs

and the bondsmen, and the modern representative state is an instrument for

exploiting wage labor by capital (1972:231).

The ensemble of

hierarchal and patriarchal relationships used by the ruling class to support

its domination plays a role in the origin and evolution of civilization

comparable to that played by the gravitational field of the sun in our solar

system. One can, however, no more expect bourgeois social scientists to

understand this fact that one could expect medieval priests to accept that the

earth revolved around the sun. But that is their problem, not ours. A

scientific, materialist understanding of the rise and evolution of civilization

must focus on the processes by which the ruling class establishes and maintains

its rule.

That such understanding

must begin with Engels does not mean that it must stop there.[5]

We must recognize both the strengths and weaknesses of Engels's formulations

and incorporate more recent archaeological and ethnological thinking into his

basic model of the relationship between the state and class rule.

Many of Engels's

shortcomings flow from his treatment of the rise of the Athenian state as

"a particularly typical example of the formation of a state" which

occurred "in a pure form without any interference through use of violent

force either from without or within" (Engels 1972:181). Since they had not

yet been discovered, Engels was of course unaware of the civilizations of Minos

and Mycenae which preceded Athens in the Aegean and of ancient Sumerian civilization

which preceded the classical world by as long a time span as the classical

world precedes our own (Fagan 1983:339-355, Renfew 1972). As Khavanov remarks,

it is now clear that the Mediterranean states of antiquity,

which were marked by slave ownership on a vast scale, were by no means the

truly pristine states of that region. They had been preceded by early states

based on different systems of dependence and exploitation (1978:83)

The processes leading to

the rise of the Athenian state, in short, were by no means typical when viewed

against the backdrop of the earliest pristine civilizations of the Near East,

China, and Native America.

Linked into this, Engels

regarded commodity production as lying at the beginning of class formation

(1972:233). While this may have been true in Greece, it was much less important

in the earliest civilizations of Sumer and Egypt, where redistributive networks

associated with temples appear to have played a central role (Adams 1966).

Trade in these early empires was more state enterprise than the activity of

individual commodity producers (Polanyi 1957b). The coinage of money does not

begin until the seventh century B.C., begun by the Greek state of Lydia in Asia

Minor (Friedman 1983:350, Kroeber 1948:729). Engels's discussion of cattle as

the earliest form of property and money loses much of its force in light of

more recent archaeological discoveries.

Engels also appears to

have regarded the emergence of classes, and a ruling class, as a

"necessity" at a particular "stage in the development of

production" (1972:232), when "human labor power obtains the capacity

of producing a considerably greater product than is required for the

maintenance of the producers" (1972:234). This, however, requires

reformulation in the light of recent studies of hunters and gatherers

indicating that they are capable of meeting their subsistence needs with a few

hours labor per day (see, e.g. Carneiro 1968, Lee 1968, Sahlins 1972, Cohen

1977, but also Altman 1984, Ember 1978). Of particular importance is Carneiro's

"test" of this "surplus" theory indicating that the

productivity of labor among classless horticulturalists in the Amazonian

lowlands is higher than that of maize and potato farmers supporting a class

society in the Andean highlands (1961). Clearly, as Carneiro suggests, it is

not productivity of labor as such that is decisive, but other material

features. I believe that Carneiro is correct in pointing to size, density, and

immobility of population as the crucial variables in the emergence of class

rule, and warfare as an important catalyst (1961, 1967, 1970). Carneiro errs,

however, in seeing warfare as simply growing out of competition for land and

ignoring the desire for plunder and slaves as vital motives for warfare in

horticultural societies.

Engels is important on

this point. While in places he regards the emergence of classes as a necessity,

in other places he correctly points to greed and avarice as the motive force of

class rule:

The lowest interests - base greed, brutal appetites, sordid

avarice, selfish robbery of the common wealth - inaugurate the new, civilized,

class society. It is by the vilest means - theft, violence, fraud, treason -

that the old classless gentile society is undermined and overthrown. And the

new society itself during all the 2,500 years of its existence has never been

anything else but the development of the small minority at the expense of the

great exploited and oppressed majority; today it is so more than ever before

(Engels 1972:161).

civilization achieved things of which gentile society was not

even remotely capable. But it achieved them by setting in motion the lowest

instincts and passions in man and developing them at the expense of all his

other abilities. From its first day to this, sheer greed was the driving spirit

of civilization; wealth and again wealth and once more wealth, wealth, not of

society but of the single scurvy individual - here was its one and final aim.

If at the same time the progressive development of science and a repeated flowering

of supreme art dropped into its lap, it was only because without them modern

wealth could not have completely realized its achievements (1972:235-236).

The origin and evolution

of class society is here correctly ascribed to simple greed and avarice, not

the requirements of production.[6]

As I have suggested elsewhere (Ruyle 1973a, 1973b, 1975, 1977), it is essential

to analytically separate the modes of exploitation which support ruling classes

from the modes of production which support entire human populations.[7]

The mode of exploitation may be viewed as the "mode of production" of

the ruling class, which requires certain forms of production and large,

sedentary populations for its emergence. While such material conditions may be

necessary preconditions for the emergence of ruling classes, and while the

existence of ruling classes necessarily has a real impact on the development of

productive systems, ruling classes are not now, nor have they ever been,

necessary for the rest of the species. They are better regarded as a social

disease that has persisted because its cure has only been recently discovered.

Continuing, Engels can be

interpreted as saying that class antagonism develop, and then the state appears

to reconcile these antagonism in the favor to the ruling class. Although Fried

makes a parallel point in his distinction between stratified and state

societies as evolutionary stages (1967), I believe this is erroneous. The

evidence suggests rather that the state develops simultaneously with the ruling

class as one of the primary mechanisms by which an emerging ruling class

consolidates its rule (for discussion, pro and con, see Service 1975:285;

Classen and Skalnik 1978:12,13,621,625,628; Fried 1978).

Finally, Engels's views

on the origin and evolution of the family need to be thoroughly re-examined in

the light of developments in the study of kinship since Morgan's time. This, of

course, is beyond the scope of the present essay, but some comments are in

order since, in Engels's view, the development of the family was intimately

interwoven with the rise of patriarchy.

It is to Engels's credit

that he saw the rise of class oppression as intimately associated with the

"world historical defeat of the female sex" and the oppression of

women, in a word, with the rise of patriarchy. Engels stressed the importance

of both production and reproduction in cultural causation:

According to the materialist conception, the determining factor

in history is, in the final instance, the production and reproduction of

immediate life. This, again, is of a twofold character: on the one side, the

production of the means of existence, of food, clothing and shelter and the

tools necessary for that production; on the other side, the production of human

beings themselves, the propagation of the species. The social organization

under which the people of a particular historical epoch and a particular

country live is determined by both kinds of production: by the state of

development of labor on the one hand and of the family on the other

(1972:71-72).

Engels found Morgan's

discovery of the non-patriarchal organization of the Iroquois highly

significant:

This rediscovery of the primitive matriarchal gens as the

earlier stage of the patriarchal gens of civilized peoples has the same

importance for anthropology as Darwin's theory of evolution has for biology and

Marx's theory of surplus value for political economy (Engels 1972:83).

Several observations are

in order here. First, due credit must be given to Morgan as the "Founding

Father" of the anthropological study of kinship which "stands at the

center of anthropological science" (Fortes 1969:4, also see White

1964:xvii), but it must also be stressed that there have been major advances in

the study of kinship since Morgan's time. Here, we may simply note the

discovery since Morgan's time of the importance of post-marital residence

rules, the avunculate, ambilineal descent, and componential analysis of kinship

terminologies ("kinship algebra"). At the same time, we must also

stress the powerful influence of viricentrism on kinship studies (Schrijvers

1979). Clearly, the theory of matriarchy challenges existing gender relations

no less than the theory of primitive communism challenges existing property

relations. "Obviously this gynaecocratic view, which placed woman in a new

relation to man, was unlikely to be permanently accepted" (Hartley

1914:27). The rejection of the theory of primitive matriarchy by male

chauvinist anthropology, then, is not to be explained on purely scientific

grounds.[8]

A good deal of the

problem flows from misunderstanding of the concept of matriarchy itself. Male

chauvinist anthropologists, reasoning that patriarchy refers to a society in

which men have power to dominate and oppress women, understand matriarchy as a

society in which women have power to dominate and oppress men. Such a sinister

society, the anthropological establishment assures us, has never existed (cf.

Schjrivers 1979). However, the concept of matriarchy involves not just a shift

in who has power, but in the nature of power itself (Webster 1975:142, Briffaut

1931:179-81).[9] Male

chauvinist social science has followed Max Weber in defining power in terms of

control over others (Weber 1966:21; Caplow 1971:26), and can conceive of no

other use of power than domination.[10]

But the power of women in matriarchy is power over their own productive and

reproductive capabilities. Unlike patriarchal power which is used to dominate

and oppress women (and other men) this matriarchal power is not used to dominate

and oppress men, although women in Iroquois society do appear to have exerted

some controls over male activities. In this sense, matriarchal societies have

clearly existed, although male chauvinists may regard them as equally sinister.[11]

It must be stressed,

however, that the matriarchal gens of the Iroquois was not primitive, in the

sense of reflecting the original condition of our species. Nor was it even a

universal stage in the development of gender relations. Rather, matrilineality

appears to be an adaptation to specific material conditions, conditions which

were not universal at any phase in humanity's existence (Aberle 1961:725,

Divale 1975, Fleur-Lobban 1979:347). Gentile society (or, in contemporary

usage, societies with corporate unilineal descent groups) appears only after

the neolithic revolution, when horticulture dramatically altered the material

conditions of production and reproduction for our species. Among hunters and

gatherers, who more nearly approximate the primitive condition for humanity,

the gens, as a corporate, landowning, unilineal descent group, does not appear,

and descent is typically cognatic (Aberle 1961, but see also Ember 1978). But

even among horticultural peoples, matrilineality is less common than

patrilineality (Aberle 1961), but as Gough notes, conditions leading to

matriarchy may have been more prevalent in the past (1977). The insights of

Morgan and Engels, although still relevant for understanding the history of

gender relations, have to be evaluated in light of these more recent findings.

Engels, then, in pointing

to the relationship between the state and class rule, and between class rule

and patriarchy, provided the essential insight for the scientific understanding

of the origin and evolution of civilization. This insight, however, must be

re-formulated in the light of scientific advances since Engels's time.

Social Thermodynamics

Human societies may

usefully be thought of in ecological and thermodynamic terms, as parts of

larger ecosystems composed of matter, energy, and information (Ruyle 1976,

1977, n.d.). The material entities include the human population, its

environment (including both resources and hazards), and the social product, the

ensemble of goods (or use-values) produced by human labor. The human population

interacts with its environment through a number of thermodynamic systems: the

bioenergy (or food energy) system, the ethnoenergy (or behavioral energy)

system, and the auxiliary energy system. The flow of energy through the

ecosystem is controlled by the information within that system. For human

populations, this includes both genetic information and culture.

Evolutionary change

involves change in all of these features. While there has been no significant

genetic change in human evolution for the past 40,000 years or so, there have

been significant changes in cultural information, the human population has

grown steadily with increasing speed, increasingly powerful modes of production

have been developed, the social product has grown in size and complexity, and

there have been associated changes in our environment. Our food energy systems

have also grown, and in the process changed from foraging to horticulture and

agriculture. The auxiliary energy systems have also grown, incorporating the

energy of draft animals, wind and water power, and fossil fuels. For our

purposes, however, the most significant changes have been those in the system

of behavioral energy. To understand these changes we must look more closely at

the thermodynamic peculiarities of the human primate.

All animals expend

behavioral energy to satisfy their needs. Among humans, this energy expenditure

takes a distinctive form, labor. In contrast to the direct and individual

appropriation of naturally-occurring use values by other primates, humans

satisfy their needs through social production, using tools and cooperating to

produce a social product which is appropriated according to socially

established rules (see Figure 1.). All human beings, since australopithecine

times, have been dependent upon definite modes of production and it is this

dependence which has generated the distinctive characteristics of our species

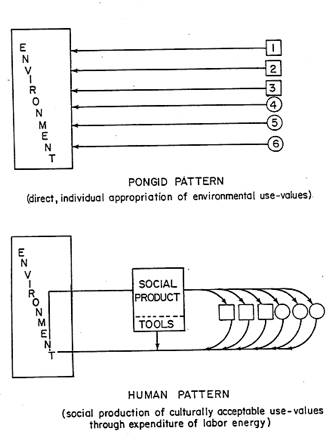

(Ruyle 1976, Woolfson 1982).

Figure 1. Energy Flow in Non-human and Human Populations.

Now, although all human

beings are dependent upon social labor, it is by no means the case that all

human beings participate in social labor. Indeed, the distinctive feature of

civilization is the existence of classes which, although they enjoy

preferential access to the social product, do not themselves engage directly in

production. Such classes live by expending their energy into a mode of

exploitation, an ensemble of exploitative techniques (such as slavery, plunder,

rent, taxation, and wage-slavery) and associated institutions of violence and

thought-control (the State-Church). Human societies, then, may be classified

into two categories on the basis of their underlying thermodynamic structure

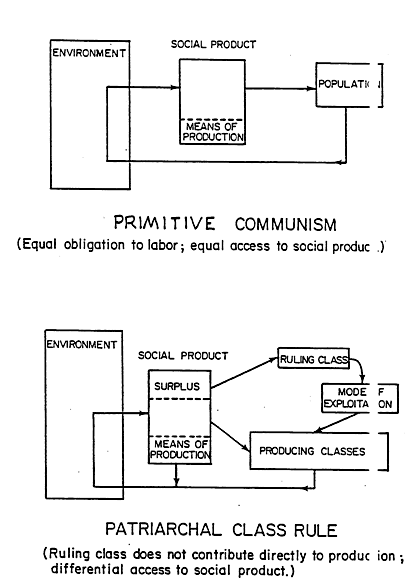

(see Figure 2.). On the one hand, there are classless societies in which all

members of society, for the greater part of their adult lives, participate

directly in production through the expenditure of their own labor power. The

primitive commune of foragers and the matriarchal clans of some

horticulturalists are examples of classless societies.

Figure 2. Energy Flow in Primitive Communism and Patriarchal Class Rule.

On the other hand, there

are class societies in which there are people who, from birth to death, enjoy

preferential access to the social product while not directly engaging in

production. All such societies are characterized by, first, a definite mode of

exploitation controlled by men who enjoy preferential access to the social

product, and second, patriarchy. It is men, not women, that control and are the

chief beneficiaries of the exploitative system. All historic and contemporary

civilizations fall into this category.

Before looking at these

two types of society, primitive communism and patriarchal class rule, in

greater detail, it may be useful to discuss the concepts of social

thermodynamics more fully. These concepts, it may be noted, are drawn from two

sources: ecological energetics and Marx's labor theory of value (see Ruyle

1977).

Just as all animal life

may be viewed as a struggle for the energy embodied in plant material and

animal flesh (White 1949:362-393), so all human life may be viewed as a

struggle for the labor energy embodied in the goods that satisfy human needs.

In capitalism, human needs are met predominately through the consumption of

commodities. The consumption of commodities is the consumption of the definite

amount of social labor embodied in those commodities, and it is the labor

energy embodied in commodities that ultimately determines, through the

mechanism of supply and demand, their exchange-value (Sweezy 1968; Marx 1969).

The exchange of commodities is, therefore, the exchange of the labor energy

embodied in those commodities. Access to the commodities that make up the

social product is acquired through money. The quest for money is, therefore, the

form that the struggle for labor energy takes in bourgeois society.

In precapitalist modes of

production this struggle for social energy takes different forms. Following

Polanyi's tripartite scheme of reciprocity, redistribution, and exchange

(1957a), we may characterize the modes of gaining access to the social product

as kinship (reciprocity), status (redistribution), and money (exchange). Each

of these modes had its own inner logic which shapes the form of struggle for

energy. In kinship systems, best exemplified by the foraging commune, efforts

at maximization are constrained by the small size and material interdependency

of the commune, as well as the ideology of kinship itself. In status systems,

best exemplified by the early empires such as the kingdom of Hammurabi in

Babylonia and the New Kingdom in Egypt, "distribution was graded,

involving sharply differentiated rations" according to status (Polanyi

1957a:51). As Claessen and Skalnik note,

Though the underlying principle of the early state is reciprocity,

the reciprocity does not appear to be

balanced: the flow of goods and labor is reciprocated mostly on the ideological

level, and, in reality, a form of redistributive exploitation prevails

(1978:638-39, see also p. 614).

Such systems are the product

of maximization efforts which tore asunder the primitive commune. Such

maximization reaches its apogee in the exchange systems of capitalism.[12]

Beneath the surface of

human social life, then, are underlying thermodynamic structures which exert

powerful influences on human behavior. It is these structures and their inner

laws of motion must be the focus of scientific analysis of the origin and

development of patriarchal system of class rule.

Before proceeding, it is

necessary to discuss two key concepts, exploitation and oppression. Although

these are intertwined, they are analytically distinct. While exploitation has

been fairly clearly defined in the scientific literature (contra Dalton 1974,

see Ruyle 1975), the term oppression does not appear either in standard

bourgeois sources (Sills 1968) or Marxist sources (Gould 1946). Nor, to the

best of my knowledge, is oppression defined within the literature of feminism

(but see Delphy 1984).

Standard dictionary

definitions of oppression include both objective ("the exercise of

authority or power in a burdensome, cruel, or unjust manner") and

subjective ("the feeling of being oppressed by something weighing down the

bodily powers or depressing the mind") aspects (Barnhart 1947:850). Clearly,

oppression is a broad concept which subsumes exploitation but includes other

social processes as well.

We may briefly define

oppression as the denial of equal access to the social product, which includes

both material goods and services as well as intellectual and spiritual

products, and denial of full development, use, and control of one's productive,

reproductive, intellectual, artistic, and spiritual powers. Such denial is

enforced by other people who, by virtue of their oppressive acts, gain

preferential access to the social product and control over the productive and

reproductive powers of the oppressed.

In addition to being a

social process, that is, some people are objectively oppressed by others,

oppression is also a subjective feeling within individuals. The objective

process and subjective feelings may, or may not, coincide. People may feel

oppressed even though, objectively, they are not, for example, members of

ruling classes after a revolution abolishes their former privileges, or someone

without musical ability wanting to be recognized as a great singer. Or people

may objectively be oppressed without necessarily feeling oppressed, for example

the mythical "happy slave" or "happy housewife."

While class and gender

oppression are intertwined, their analysis must take different forms. Class

oppression is everywhere associated with exploitation, the forcible extraction

of surplus from the direct producers by a class of non-producers. Exploitation

is a real process which can be measured in thermodynamic terms. Thus, the

average production worker in the U.S. is paid less than $20,000 per year, but

produces over $60,000 worth of value-added to the finished product (U.S. Bureau

of the Census 1984:746). The difference of $40,000, what we Marxists call

surplus value, is appropriated by the capitalist. In short, two-thirds of the

labor energy of the average worker in the United States is appropriated by the

bourgeoisie. By contrast, a capitalist with $10,000,000 to invest can, at a

modest 5% in tax free municipal bonds, receive $500,000 yearly with a minimum

expenditure of effort. The exploitation of peasants or slaves in precapitalist

systems is equally clear as this exploitation of wage-slaves in capitalism.

Class systems almost

invariably include groups of oppressed people who are not exploited in the

strict sense of the term. The unemployed in capitalism and the underclass of

agrarian empires are clearly oppressed as we have defined the term, but are not

sources of surplus for the ruling class, even though their existence

facilitates the extraction of surplus from the direct producers.

Class oppression, then,

takes the form of denial of equal access to the social product and associated

forms of threats, violence, and thought control to support this denial. It is

directly linked into a system of exploitation for the extraction of surplus

from the direct producers.

The oppression of women

is more complex.[13] It may, and

usually does, include exploitation. But it also includes other forms of

oppression, unique to gender oppression, such as the denial of the exercise of

productive, reproductive, intellectual, artistic, and sexual powers. The forms

of such oppression, as Engels correctly saw, varied with the class position of

the woman, or rather of the man to whom she is attached, since the class

position of a women is often determined by that of the men to whom she is

attached.

Women are significant

objects of class exploitation. Marx was no doubt correct when he saw that women

were the first exploited group (Meillassoux 1981:78), as female slavery appears

to antedate male slavery and remains more important than male slavery in early

Mesopotamia (Adams 1966:96-97, 102), and probably ethnographically as well.[14]

The exploitation of women workers has been important in every phase of

capitalist development, and women continue to function as a disadvantaged

minority group within the labor market. Such sexual discrimination within the

capitalist labor market, together with racial and ethnic discrimination, is an

essential feature of capitalism (Ruyle 1978). It is no accident, therefore,

that women form the bulk of the poor in contemporary capitalism.

In addition, however,

there are other forms of gender oppression. The women of the ruling classes are

typically not exploited in the Marxist sense, since no economic surplus is

extracted from them. But even with servants to attend them, upper class women

are oppressed if they are denied the exercise of their intellectual and

productive powers and control over their own reproduction. The roots of such

oppression lie in what Veblen termed "conspicuous consumption" of

ruling class men:

In order to gain and to hold the esteem of men it is not

sufficient merely to possess wealth or power. The wealth or power must be put

in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence. And not only does the

evidence of wealth serve to impress one's importance on others and to keep

their sense of importance alive and alert, but it is of scarcely less use in

building up and preserving one's self-complacency. . . . One portion of the

servant class, chiefly those persons whose occupation is vicarious leisure,

come to undertake a new, subsidiary range of duties - the vicarious consumption

of goods. . . . Another, scarcely less obtrusive or less effective form of vicarious

consumption, and a much more widely prevalent one, is the consumption of food,

clothing, dwelling, and furniture by the lady and the rest of the domestic

establishment. . . . So long as the woman's place is consistently that of a

drudge, she is, in the average of cases, fairly content with her lot. She not

only has something tangible and purposeful to do, but she has also no time or

thought to spare for a rebellious assertion of such human propensity to

self-direction as she has inherited. And after the stage of universal female

drudgery is passed, and a vicarious leisure without strenuous application

becomes the accredited employment of the women of the well-to-do classes, the

prescriptive force of the canon of pecuniary decency, which requires the

observance of ceremonial futility on their part, will long preserve high-minded

women from any sentimental leaning to self-direction and a "sphere of

usefulness" (Veblen 1953:42,60,232-33).

Ruling class women,

however, are not necessarily reduced to mere consumers of the surplus gained by

their predatory mates. Domhoff has analyzed the role of American ruling class

women in preserving the class system by not only establishing the canon of

invidious consumption, but also in maintaining the class lines through social

functions (debutante balls, parties, marriage arrangements, etc.) and in social

welfare work which increases the dependency of the poor on the well-wishes of

the rich (1971).

In the lower, but still

"respectable," classes, the dependence of women on men's claims to

the social product enforces "the open or concealed domestic slavery of the

wife":

In the great majority of

cases today, at least in the possessing classes, the husband is obliged to earn

a living and support his family, and that in itself gives him a position of

supremacy without any need for special legal titles and privileges. Within the

family, he is the bourgeois, and the wife represents the proletariat (Engels

1972:137).

Or, as Firestone

perceptively notes:

There is also much truth in the clichés that "behind every

man there is a woman," and that "women are the power behind [read:

voltage in] the throne." (Male) culture was built on the love of women,

and at their expense. Women provided the substance of those male masterpieces;

and for millennia they have done the work, and suffered the costs, of one-way

emotional relationships the benefits of which went to men and to the work of

men. So if women are a parasitical class living off, and at the margins of, the

male economy, the reverse too is true: (Male) culture was (and is) parasitical,

feeding on the emotional strength of women without reciprocity. . . . Men were

thinking, writing, and creating, because women were pouring their energy into

those men (1971:127, 126).

Thus, although the

domestic slavery of women may be analyzed in thermodynamic terms (but somewhat

differently than wage slavery), and correctly seen as exploitation, this is not

the sole dimension of women's oppression. No economic surplus is obtained by

denying middle class women the exercise of their productive powers. What is

obtained, rather, is support for the man in his exploitative activities, by

providing a emotionally secure refuge. Perhaps we may borrow DeVos's (1967)

concept of "expressive exploitation" for the use of women as

consumers of leisure to enhance the invidious distinctions among men, and as

providers of support for the predatory activities of men.

Finally, we may note the

existence of sexual oppression, both in using women as sex objects and in

denying women's rights to sexual gratification. The use of women as sexual

objects is an ubiquitous form of oppression. Whether this occurs in the harems

of Oriental despots or in more mundane forms of prostitution, the object of

such sexual exploitation is not surplus value in the Marxist sense.

Neither class nor gender

oppression are universal in human societies (although, as we shall note, there

are differences of opinion on the universality of the gender oppression). They

do not appear in primitive communism, and only become universal with the rise

of civilization.

Primitive Communism

The theory of primitive

communism proposed by Morgan and Engels has not been well received by bourgeois

anthropology (see White 1959:55-56), no doubt due to a reluctance to admit that

our ancestors were communists. But there is general agreement on the

egalitarian and communal nature of foraging society, regardless of the term

used (see, e.g. Coon 1971, Fried 1967, Flannery 1972, Harris 1971, Service

1962, 1975, White 1959).

Contemporary foraging

peoples cannot, of course, be simply equated with the foragers of prehistory,

since 1. they occupy marginal areas rather than the most productive areas

occupied by prehistoric foragers, 2. they are usually in close contact with horticultural

and state-level peoples, and 3. there has been acculturation due to contact

with the West. Nevertheless, such peoples provide our best source of

information about the kinds of life-styles that existed prior to the neolithic

revolution. Archaeological evidence confirms the similarities in population

size, settlement patterns, and subsistence technologies between prehistoric and

contemporary foraging peoples. It is reasonable to assume, therefore,

considerable overlap between the ranges of variation of contemporary and

prehistoric foraging societies (Clark 1967:12, Woodburn 1980:113, but see also

Makarius 1979).

The basic features of the

foraging commune are well established. As Leacock and Lee note:

In our view there is a core of features common to band-living foraging societies around the world. Extraordinary

correspondences have emerged in details of culture between, for example, the

Cree and the San, or the Inuit and the Mbuti. These features, however, differ

from a number of cases such as California and the Northwest Coast of North

America where relations of production, distribution, exchange, and consumption

have more in common with many horticultural peoples than with other foragers.

Similarities among

foragers include: egalitarian patterns of sharing; strong

anti-authoritarianism; an emphasis on the importance of cooperation in

conjunction with great respect for individuality; marked flexibility in band

membership and in living arrangements generally; extremely permissive

child-rearing practices; and common techniques for handling problems of

conflict and reinforcing group cohesion, such as often-merciless teasing and

joking, endless talking, and the ritualization of potential antagonisms. Some

of these features are shared with horticultural peoples who are at the

egalitarian end of the spectrum, but what differentiates foragers from

egalitarian farmers is the greater informality of their arrangements

(1982:7-8).

The underlying

thermodynamic structure of the foraging commune is simple and clear: it is a

classless society with equality of access to the social product and equal

obligation to participate directly in productive labor. No one can expect to

live their lives on the labor of others, and no expects to be exploited

throughout their lives. There are no special instruments of violence and

thought control, but rather equality of access to violence and to the sacred

and supernatural worlds.

Although the absence of

class oppression among foragers is clear, the question of gender oppression is

more complex. Leacock has presented abundant ethnographic documentation for her

egalitarian model of gender roles in foraging societies, and suggested that

evidence to the contrary is best explained as due either to acculturation or

viricentrism among ethnographers, or both (1972, 1975, 1977, 1978). But others

suggest that women are universally subordinate, in some degree, in all

societies, including foraging societies (Rosaldo 1974, Ortner 1974, Gough 1975,

Harris 1977, Firestone 1971, de Beauvoir 1952). Even those who take this latter

view, however, acknowledge that women's oppression is less among foragers than

in class society. Gough, for example, stresses that:

In general in hunting societies, however, women are less

subordinated in certain crucial respects than they are in most, if not all, of

the archaic states, or even in some capitalist nations. These respects include

men's ability to deny women their sexuality or force it upon them; to command

or exploit their produce; to control or rob them of their children; to confine

them physically and prevent their movement; to use them as objects in male

transaction; to cramp their creativeness; or to withhold from them large

segments of the society's knowledge and cultural attainments (1975:69-70).

To the best of my

knowledge, no one has suggested that patriarchal institutions comparable to

those of historic civilizations existed in foraging societies, although village

societies may provide some comparable examples (i.e. the Yanomamo). Rather,

gender roles among foragers are characterized by free and equal access to

strategic resources and the social product by "the complementarity and

interdependence of male and female roles" (Caufield 1985:97; 1981).[15]

There is, of course,

considerable variability in foraging societies. Friedl notes four patterns of

the sexual division of labor among foragers (1975:18-19). In the first,

represented by Hadza of Tanzania and the Paliyans of Southwest India, hunting

is of little importance and both men and women gather on a largely individual

basis, with little food sharing and little meat for distribution. In the

second, represented by the Washo of the Great Basin of North America and the

Mbuti pigmies of the Congo rain forests, both men and women participate in

collective hunting, although men do the actual killing, and also both sexes

participate in gathering activities, with food shared among the work team. In

the third, represented by the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert in south Africa

and the Tiwi of north Australia, there is a clear division of labor in which

men hunt large game animals which provide 30 to 40 per cent of the food supply,

and women gather plant foods and small animals. In the fourth, represented by

the Eskimo, the game provided by men is virtually the only source of food, and

women are almost totally dependent on the men for all foodstuffs and raw

materials. The "Caribou-Eater" Chipewan of northern Canada, among

whom men's hunting activity provides over 90 per cent of the food supply, are

another example (Sharp 1981).

The differential control

over the distribution of meat has been suggested to be a crucial variable

determining the relative statuses of men and women (Friedl 1975). Where men's

hunting provides a substantial percentage of the food supply, men appear to

enjoy greater dominance, and the position of women appears most oppressive

among the Eskimo and Chipewan (Friedl 1975, Sharp 1981, but see also Sachs

1982, Fleur-Lobban 1979, Caufield 1981, Briffaut 1931)

In this connection, the

Agta pigmies of the Philippines are of crucial importance, for Agta women hunt

equally with men, using bows and arrows and other techniques to hunt wild pigs

and deer (Estioko-Griffin and Griffin 1981). The Agta clearly demonstrate that

neither physical size and strength nor child bearing and child rearing prevent

women from hunting. The Griffins point out that Mbuti pigmy men kill elephant

and buffalo, and suggest that the robust Neanderthal women could certainly have

done the same (Estioko-Griffin and Griffin 1981:146). They further suggest that

the Agta data deny the universality of the woman-the-gatherer

model, and go far to advance the concept of hunter-gatherers as incredibly

flexible in all their organizational characteristics. Subsistence activities as

well as social organization may be so malleable that whatever the environmental

pressures for and historical trajectory of culture change, hunters may shift

people into whatever food-getting pursuits will keep everybody fed (1981:143).

Pursuing this suggestion,

we may note also the plasticity of social behavior among the apes, from the

monogamous gibbons to the group living of chimps, and among baboons, from the

harems of Hamadryas baboons to the troops of the savannah (Jolly 1972). Among

lions, it is the females that "usually do the hunting in a pride,"

and hunting hyenas are "usually led by a female" (Schaller and

Lowther 1969:331, 318). We may further note that there is no task, with the

possible exception of metallurgy, from which women are completely excluded (Sacks

1979), certainly not hunting, not warfare (Harris 1978:119), and not, as the

example of Harriet Tubman shows, plow agriculture (Nies 1978:39). Clearly, a

high degree of diversity likely characterized all phases of human evolution.

Although it seems reasonable to suppose that a sexual division of labor between

man the hunter and woman the gatherer was a common pattern, it is equally

reasonable to deny that it was universal or even the norm.

Some see the egalitarian

character of foraging societies in negative terms, as simply due to the

undeveloped state of production - since H&G's are so poor in material

terms, and produce no surplus, they "naturally" have no economic

inequality (see, e.g. Lenski 1966). Such a view, however, ignores the key

structural differences between primitive communism and patriarchal class rule.

The umbilical cord of mutual interdependence binding foragers to the commune

enjoins each member to share and to refrain from aggressive and domineering

behavior, since such behavior would jeopardize the very social relations upon

which every individual depends. The liberty, equality, and solidarity of the

primitive commune, then, are positive features rooted in the material

conditions of the foraging mode of production.

There is a tendency to

view the foraging commune as a kind of "golden age" of humanity, vide

the "original affluent society" thesis of Sahlins (1972). There is

some justification for this, since diet and labor conditions compare favorably

with those of peasants in class society, class oppression was not yet

developed, and gender oppression was, at worst, sporadic. But primitive

communism should not be viewed as idyllic, for humanity was still subjected to

the forces of nature. Hunger, disease, high rates of infant mortality, forced

infanticide and abandonment of the aged were common. Nonetheless, primitive

communism was a viable and technologically progressive social order for the

greater period of humanity's existence. Foraging societies compare favorably

with horticultural societies and with peasants in civilized societies in terms

of their vital statistics, and it is not until the Industrial Revolution that

dramatic changes occur (Dumont 1975).

In summary, then, the

underlying thermodynamic structure of the foraging commune reflects the

"free and equal association of the producers," with a universal

obligation to participate in social labor and free and equal access to the

social product. Associated with this, there is equality of access to violence

(at least for men), to strategic resources, and to the sacred and supernatural.

Although gender roles vary from near androgyny to male dominance, the norm

appears to be closer to complementary and interdependence of men and women,

with both sexes enjoying considerable autonomy in their productive and

reproductive lives. Completely lacking are the features of patriarchal class

rule: male control over women's productive and reproductive powers, forcible

extraction of surplus through exploitative techniques, and specialized institutions

of violence and thought control. In their stead, the foraging commune was

characterized by, as Morgan and Engels correctly saw, liberty, equality, and

solidarity.

Patriarchal Class Rule

In contrast to the rough

equality of primitive communism, class societies are marked by gross

differentials in access to the social product. The last five thousand years of

human evolution have been dominated by men who, although they do not

participate directly in production, nevertheless are abundantly provided with the

good things in life. In all civilizations, those classes (slavemasters, nobles,

landlords, capitalists) that contribute the least amount of labor energy to

production receive the greatest rewards, while those classes (slaves, serfs,

peasants, workers) that contribute the most receive the least. Further, all

civilizations are patriarchal, in that men tend to enjoy preferential access to

the rewards of society and control over the productive and reproductive powers

of women, who bear the greater burdens of exploitation and oppression. Why is

this?

Bourgeois social science

would have us believe that "society" rewards some people, mostly men,

because they contribute something more important than labor to society -

brains, managerial skill, technical expertise, valor, or whatever - but this is

clearly nonsense[16] As Rousseau

remarked, this is

a question slaves who think they are being overheard by their

masters may find it useful to discuss, but that has no meaning for reasonable

and free men in search of the truth (as quoted by Dahrendorf 1969:20).

The real explanation is

quite different.

The emergence of wealthy,

leisured classes occurs simultaneously with the emergence of special

instruments of violence and thought control that are staffed and/or controlled

by those men who enjoy special privileges and wealth. It seems reasonable,

therefore, to conclude that the wealth and privileges of ruling classes result

from the activity of the members of the ruling class itself. This activity

takes the form of expenditures of energy into a mode of exploitation which

pumps surplus labor out of the direct producers and into the exploiting

classes. It is thus not "society" that rewards the wealthy and

powerful; they reward themselves. They accomplish this by manipulating a mode

of exploitation which may be thought of as the "mode of production"

of the ruling class.

A mode of exploitation

has three sets of components (the analysis here is of precapitalist modes of

exploitation; modern modes of exploitation require a somewhat different

analysis - see Ruyle 1977). First of all, there are the exploitative

techniques, the precise instrumentalities through which surplus is pumped out

of the direct producers and into the ruling class. These may be direct, such as

simple plunder, slavery, taxation, or corvee, or indirect, such as rent,

managerial exploitation (or differential withdrawal from a redistributive

network), or various forms of market exchange, including wage labor. Second,

there is the State, which monopolizes legitimate violence and is thereby able

to physically coerce the exploited classes. Third, there is the Church, which

monopolizes access to the sacred and supernatural and is thereby able to

control the minds of the exploited population. These elements, or functions, of

the mode of exploitation are combined in different ways by different ruling

classes. The State and the Church, for example, may be institutionalized

separately, as in medieval Europe and Japan, or they may be combined into a

single unitary institution, as in many bronze age civilizations.

The State and the Church,

then, form twin agencies of oppression whose purpose is to support and

legitimate ruling class exploitation and the wealth and privileges resulting

from this exploitation. But in addition to their repressive role, these

agencies also carry out a variety of socially beneficial functions.

Marx once wrote of the

Asiatic state:

There have been in Asia, generally, from immemorial times, but

three departments of Government: that of Finance, or the plunder of the

interior, that of War, or the plunder of the exterior; and finally, the

department of Public Works (1969:90).

Marx's statement here

calls our attention to the dual role of the State, as an agency of oppression

and of government. Generally speaking, the State carried on the following

functions in developed class societies: waging war, suppressing class conflict,

protecting private property, punishing theft, constructing and maintaining

irrigation works, running state monopolies of key economic resources,

regulation of markets, standardization of weights and measures, coinage of

money, maintaining roads, and controlling education (see White 1959:314-23).

The Church is often

viewed as a religious institution, but it is also an important agency of social

control. This is well understood by the theoreticians of the Catholic Church.

Pope Leo XIII, for example, declared that

God has divided the government of the human race between two

authorities, ecclesiastical and civil, establishing one over things divine, the

other over thing human (as quoted in White 1959:303).

The importance of the

Church in social control is made even more explicit in the following statement

of Pope Benedict XV:

Only too well does experience show that when religion is banished,

human authority totters to its fall . . . when the rulers of the people distain

the authority of God, the people in turn despise the authority of men. There

remains, it is true, the usual expedient of suppressing rebellion by force, but

to what effect? Force subdues the bodies of men, not their souls (as quoted by

White 1959:325).

The implication is clear.

Only the Church can subdue the souls of human beings and make them accept the

oppressiveness of class rule. Leslie White has provided abundant documentation

of the role of the Church in subduing the souls of human beings and supporting

the ruling class by 1) supporting the State in its functions of waging war,

suppressing class struggle, and protecting private property, and 2)

"keeping the subordinate class at home obedient and docile" (White

1959:303-328). The content of the religious ideology promulgated by the Church

helps fulfill this latter function by promising the subordinate class in the

afterlife the rewards they are denied in this world, and by threatening the

punishment of Hell for misbehavior in this world.

The Church also plays an

important role in legitimating the system by teaching that the social order is

an extension of the natural and sacred orders. This legitimation has a dual

aspect. First, there is the manipulative, thought control aspect in which the

content of religious ideology is consciously shaped in order to support the

existing system. Second, and also very important, is the legitimation of the

system to the rulers themselves. Max Weber discussed the latter aspect as

follows:

When a man who is happy compares his position with that of one

who is not happy, he is not content with the fact of his happiness, but desires

something more, namely the right to this happiness, the consciousness that he

has earned his good fortune, in contrast to the unfortunate one who must

equally have earned his misfortune. . . . What the privileged classes require

of religion, if anything at all, is this psychological reassurance of

legitimacy (1963:106-107).

It is important to

distinguish between religion and the Church. Religion is any body of ideas

about the sacred and supernatural. As such, it precedes class society and plays

important functions even in primitive communism. In class society, religion

becomes an arena of class struggle and religion becomes divided into the

religion of the oppressed and the religion of the oppressor. It is the latter

which is promulgated by the Church, a social organization, controlled by the

ruling class, which uses religion for purposes of thought control. In modern

systems, it may be noted, these thought control functions are largely taken

over by other institutions such as the mass media and educational system, so

that the role of the Church is somewhat reduced.[17]

This mode of

exploitation, including an ensemble of exploitative techniques, the State, and

the Church, is the instrumentality through which a predator-prey relationship

is established within the human species in which the stakes are human labor

energy rather than the energy locked up in animal flesh. The differentials of

wealth, privilege, and prestige which characterized all historic civilizations

are created by this predatory relationship between ruler and ruled.

Once this predatory

relationship is established, the system of exploitation becomes larger and more

complex, with a complex division of labor developing not only in the sphere of

production (between agricultural workers and workers in the industrial arts,

metallurgy, textiles, pottery, etc.) but also in the sphere of exploitation

(warriors, priests, scribes, etc.). The result is an elaboration of occupations

and statuses among the different kinds of producers, exploiters, parasitic

groups, and so on. This predatory relationship between rulers and ruled, then,

generates the division of the population into classes, which are best defined

by their relationship to the underlying flow of labor energy through the

population.

The surface structure of

developed class societies may be quite complex, and the fundamental class

opposition between ruler and ruled is likely to be overlaid and concealed by a

more diversified arrangement of classes attached to the flow of social energy

in a variety of ways. The ruling class is composed of a group of intermarrying

patriarchal families who, in addition to controlling their own sources of

wealth in the form of landed estates typically worked by peasant labor, also

control the key positions in the State-Church bureaucracies. In addition to the

ruling class itself, there are typically privileged retainer classes

(officials, scribes, priests), various divisions within the producing class

(between peasants and artisans and between rich and poor peasants, for

example), and finally an underclass (composed of outcastes, outcasts, beggars,

and thieves), which may not be directly exploited but which nonetheless plays

an important role the overall system of exploitation.

Two additional points

need to be made. The first is that exploitation necessarily generates

resistance so that class rule is invariably accompanied by class struggle. The

history of civilization, as Marx and Engels correctly pointed out, is the

history of class struggle (1964). Class struggle, together with the progressive

development of the forces of social production, have been the motive forces of

cultural evolution during the period of historic civilizations.[18]

The second is that

systems of class rule are invariably patriarchal.[19]

The oppressive agencies of State and Church are typically staffed by men, and

men are both the prime movers and primary beneficiaries of the system of

exploitation. Women, typically, are defined by their relationship to men, and

their place in the system is determined by their relationship to their fathers,

husbands, and sons. Women are also typically reduced to an inferior position in

class societies. But just as men struggle against class rule, so women struggle

against patriarchy. It is men who write history, however, and this gender

struggle has been poorly documented, and those sources which exist have been,

until quite recently, generally ignored (see, e.g., Carroll 1976).

Barrett has suggested

that the term patriarchy be restricted, since in its present usage it is

"transhistorical" (1980). A term that can be applied to so many

different societies, it may be argued, has lost all utility for social

analysis. Similar arguments, of course, could be made in favor of abandoning

the term "class rule." I believe such arguments are fundamentally

erroneous, for all systems of patriarchal class rule share underlying

structural features which set them off from both the primitive communism that

preceded them, and from the emerging socialist world that is replacing them.

The nature of these structural features, and how they generate the superficial

differences between historical systems of patriarchal class rule, are valid

topics for scientific analysis.

Neither patriarchy nor

class rule are "transhistorical," but are rather historically

limited, in that they develop after the neolithic revolution. They thus occupy

less than one percent of the period of humanity's existence.

This is a vital point,

for it underlines the fact that male dominance and women's oppression are

culturally, not biologically, determined. They are products of human activity

and can therefore be changed by human activity.

This does not deny that

male chauvinism may have existed in some foraging societies. But, as we noted

earlier, these are isolated, localized instances. It was not until what Engels

called "the world historical defeat of the female sex" that male

chauvinism became general in human societies.

Even after the rise of

patriarchy, however, women were able to maintain some equality with men in some

groups within larger systems of patriarchal class rule. But again, these are

localized instances which do not characterize the systems as wholes. The

attempt to define precisely the conditions under which male chauvinism

flourishes among hunters and gatherers and sometimes wanes within civilized

societies is a useful and important task, but it should not detract from

recognition of the general tendencies of these two forms of society, tendencies

which are quite clear when we compare the two forms of society in their

totality.

The motive force of

patriarchal class rule is the greed and avarice of the male rulers. This is not

simply the desire for a decent life, but a passion to live better than the rest

of society. Women, of course, are by no means immune from such ambition

(although, as a group, they are probably less susceptible to it than men), but

women, on the one hand, have fewer opportunities to satisfy such ambitions,

and, on the other, they typically satisfy such ambitions through men. For these

reasons, it is the greed and avarice of men that is dominant in the origin and

maintenance of class rule.

This underlying motive

force, of course, is manifest in different ways depending on historically

conditioned material circumstances. Just as patriarchal class rule is based on

a variety of different modes of production (from the irrigated wheat and barley

cultivation of ancient Sumeria and Egypt, through the chinampas of the Aztecs,

the potato farming of the Incas, the rice paddies of east and south Asia, to

the industrial agriculture of modern Euro-American capitalism), so different

modes of exploitation are developed by different ruling classes: the

bureaucratic mode of the Chinese gentry, the feudal mode of the Japanese

samurai, the slave mode of ancient Athens, and the modern bourgeois mode of

exploitation.

Similarly, the forms of

oppression of women vary from patriarchy to patriarchy. The oppression of

middle class women in the capitalist patriarchies of Europe and the United

States have, of course, been most intensively analyzed by feminists. These

exhibit clear differences from capitalist patriarchy in Japan and from the

patriarchal oppression of southern womanhood before (and after) the Civil War,

the foot-binding of the daughters of the Chinese gentry, the suttee inflicted

on Hindu women, and the purdah imposed on Arabic women.

Also, the forms of

oppression vary along class lines within patriarchal systems. Engels analyzed

the different forms of the oppression of women in the bourgeois and proletarian

families of his time, and we may not also the differences between gentry and

peasant families in Chinese patriarchy and between samurai and peasant families

in feudal Japan. We may note here also the existence of matrifocal families

among the most oppressed groups within capitalist patriarchy.

All of this is not to

suggest that women are universally mere pawns in the game of male power.

Clearly, they have sources of strength within the system (Collier 1974,

Schlegal 1972, Webster 1975:152). Nor, for that matter, are women pure

innocents, as Domhoff's study of the role of ruling class women in the United

States in maintaining capitalism indicates (1971). Women play a key role in the

training of young patriarchs, and, as the example of the Chinese mother-in-law

indicates, use their own power to oppress other women. The games women must

play, however, are typically different from those of men. In some cases,

however, women may even become adept at playing the male power game, as

numerous examples from history indicate.

None of this, however,

negates the underlying structure of patriarchy which is manifest in the

universal facts that men have greater access to power, prestige, and wealth in

patriarchy and women suffer disproportionately from oppression in patriarchy.

Although patriarchal

systems of class rule take a variety of forms, they also exhibit remarkable

similarities. The central feature is everywhere a predatory ruling class that

uses a definite mode of exploitation to extract surplus from the direct

producers, thereby supporting their own wealth and privilege. The ruling class

is composed of a group of intermarrying patriarchal families whose male members

staff the key positions in the political and religious structures supporting

class rule and whose female members are largely restricted to the domestic sphere.

There is variation, however, in the degree of discrimination against female

participation in the politico-religious system. In Japanese history, at least

since the Heian period, the Emperor and the Shogun were invariably men, while

in England women could, and as in the cases of Queen Elizabeth and Queen

Victoria, assume the leading political role (which, however, did not improve

the general position of women any more than did the election of Margaret

Thatcher as Prime Minister).

The ruling class almost

invariably lives in the cities, for good reasons. In addition to providing

protection from invaders and marauders that may plague the countryside, the

cities also provide ruling class families with the best access to the

State-Church organizations, usually based in the cities, and to the luxuries of

urban life (Sjoberg 1960).

Marriage within ruling

class families is rarely left up to the bride and groom, for marriage is a

crucial way of forming and cementing alliances within the ruling class. The

marriage networks of ruling class families extend across ethnic boundaries, as

in medieval European civilization, and even across civilizations. Cleopatra of

Egypt and Asoka of India, for example, were linked together by affinal ties in

what Darlington calls an "intercontinental ruling caste"

(1969:224-27).

The mode of exploitation

and the organization of the ruling class also varies. Typically, the

exploitation of the peasants is primary; the importance of slave-labor in

ancient Greece is unusual, although slaves are ubiquitous in precaptialist

civilizations. The State-Church organization is also variable, sometimes being

headed by a single person, as in Japan, or sometimes being separate.

Beneath the ruling class

are, typically in precapitalist systems, a retainer class which does much of

the actual work of ruling by staffing the lower levels of the

politico-religious systems, an urban artisan class, usually with a guild

organization, a peasantry, usually with internal class divisions between rich

and poor peasants, and an underclass, made up of outcastes and outcasts. The

divisions between these classes may be rigid, as in Tokugawa Japan, or fluid,

as in bureaucratic China, so that there are differing degrees of, social

mobility both between and within different class systems.

In capitalist patriarchy,

of course, the class structure is quite different.

The essence of

civilization, then, lies in exploitation. It is exploitation that generates the

distinction between ruler and ruled, and the struggle between them. The unique

accomplishments of civilizations in writing, in arts and sciences, in

architecture, and so forth, are based upon exploitation. Once this is

understood, the question of the origin of the state and civilization becomes

transformed into a question about how exploitation began.

The Transition From Primitive Communism

To Patriarchal Class Rule.

Since bourgeois

anthropology generally ignores or denies the central role of exploitation in

civilization, it has been unable to provide any convincing explanation for the

origin of civilization. Once the oppressive nature of civilization is

understood, however, we may begin to ask the right questions, and examine with

greater precision how the liberty, equality, and solidarity of primitive

communism became transformed into the oppression, inequality, and male

chauvinism of civilization.

The answers lie in the

changed material conditions of social life after the Neolithic Revolution. With

the development of a sedentary way of life based on village farming, certain

men began to develop techniques for exploiting first women, and then other men.

This led to what Engels called "the world historical defeat of the female

sex" (1972:120). We may add that this was also a defeat for the greater

part of the male sex as well.

This defeat was not

accomplished all at once, nor everywhere in the same manner. Its motive,

however, was everywhere the same: the predatory impulses of men. Curwen

(1953:3-5) notes that, "Apart from theft or plunder, there are three ways

in which you may obtain your supply of food": food collecting (hunting and

gathering), food production (with domesticated plants and animals), and

industry. Curwen should not have given such short shift to theft and plunder,

however, for they are the basis of all civilization. At least since Aristotle,

social theorists have seen property as the basis of civil society, and, as

Proudhon reminds us, "What is property? Theft!" (Mandel 1968:88).

No less than modern

bourgeois civilization is founded on wealth stolen from the workers, early

civilizations from Ur to Teotihuacan were founded on wealth stolen from the

peasants. Just as Marx revealed the precise instrumentality and analyzed in

detail the consequences of this theft in modern society, so we must analyze the

instrumentality and consequences of the early systems for extracting surplus

from the peasant producers. For, as Marx stressed,

The specific economic form, in which unpaid surplus labor is

pumped out of the direct producers, determines the relation between rulers and

ruled, as it grows immediately out of production itself and, in turn reacts

upon it as a determining agent. . . . It is always the direct relation of the

owners of the means of production to the direct producers which reveals the

innermost secret, the hidden foundation of the entire social structure

(1966:791, as quoted by Baran 1957:44).

So too will it shed light

on the problem of the origin of civilization. For civilization began when some

men began to devise ways for exploiting first women, and then other men.

We cannot be sure exactly

how this was accomplished, but let me discuss some aspects of the process with

reference to the fishing societies of the Indians of the Northwest Coast (see

Ruyle 1973b).

Wealth may be gained

through labor or through exploitation. A man may, for example, stand on a rock

and spear salmon for 5 hours and obtain 50 salmon, or 10 per hour. By extending

his hours of labor, he can increase his return, but only in proportion to his

increase in labor expenditure. If, however, he declares himself the owner of

his rock and guards "his" rock with a war club and permits five other

men to spear fish from "his" rock only on condition that they give

him one half of their catch, his return will then be one half of the ten fish

speared by each of the five men, or 12 x 10 x 5, or 25 fish per hour. In five

hours, then, he can obtain 125 fish, more than he could obtain in twelve hours

of his own labor. Clearly, one can obtain wealth much more rapidly through

exploitation than through labor.

Certain points need to be

made. First, the efforts at guarding the rock, although they provide a high

rate of return for the owner, are not productive labor since they do not

contribute directly to production.

On the other hand,

exploitation does lead to an intensification of production, since each of the

direct producers must now work ten hours in order to obtain 50 fish each, and

the total number of fish produced will be 500 - 250 going to the direct

producers ad 250 to the "owner". In an egalitarian setting, with six

people fishing five hours each, only 300 fish would have been produced.

Such exploitation is

possible only under certain circumstances. First of all, in the example given,

the "owner" must be able to control access to strategic resources. If

there were other fishing rocks downstream, the producers would have fished

there instead of working twice as hard on the "owner's" rock. Or if,

instead, there were five hunters hunting kangaroo in the Australian desert, it

would be much more difficult to control their activities.

Second, it must be

possible to store and accumulate wealth. What can anybody do with 250 fish? It

must be possible to store them or transform them into other forms of wealth.

Clearly, exploitation is not practical among nomadic foragers. A sedentary way