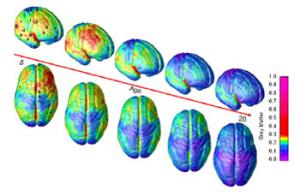

| A time-lapse 3-D movie that compresses 15 years of human brain maturation, ages 5 to 20, into seconds shows gray matter – the working tissue of the brain's cortex – diminishing in a back-to-front wave, likely reflecting the pruning of unused neuronal connections during the teen years. Cortex areas can be seen maturing at ages in which relevant cognitive and functional developmental milestones occur. The sequence of maturation also roughly parallels the evolution of the mammalian brain, suggest Drs. Nitin Gogtay, Judith Rapoport, NIMH, and Paul Thompson, Arthur Toga, UCLA, and colleagues, whose study is published online during the week of May 17, 2004 in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"To interpret brain changes we were seeing in neurodevelopmental

disorders like schizophrenia, we needed a better picture of how the

brain normally develops," explained Rapoport. |

|

| Time-Lapse Imaging Tracks Brain Maturation from ages 5 to 20 -- Constructed from MRI scans of healthy children and teens, the time-lapse "movie", from which the above images were extracted, compresses 15 years of brain development (ages 5 - 20) into just a few seconds. Red indicates more gray matter, blue less gray matter. Gray matter wanes in a back-to-front wave as the brain matures and neural connections are pruned. Areas performing more basic functions mature earlier; areas for higher order functions mature later. The prefrontal cortex, which handles reasoning and other "executive" functions, emerged late in evolution and is among the last to mature. Studies in twins are showing that development of such late-maturing areas is less influenced by heredity than areas that mature earlier. (Source: Paul Thompson, Ph.D., UCLA Laboratory of Neuroimaging) |