|

|

|

Map showing Miletus from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Miletus_Bay_silting_evolution_map-en.svg |

Bust of Thales (624-546BCE) from http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/T/Thales.html |

Philosophy’s Movement Toward Cognitive Science

Early Beginings of Science and Philosophy

Early philosophy tends not to distinguish strongly between different areas of inquiry. For the most part the earliest Greek philosophers, for example, Thales of Miletus (624-546 BCE), speculate as to the most basic elements of the world, and how these elements result in all other objects, properties, and events. Thales supposes that water is the most basic element, and all other objects, properties, and events result from changes to water. Scholars commonly identify Thales as the first philosopher in the western tradition, and Miletus, a city on the coast of present-day Turkey, as western philosophy’s point of origin. Thales reportedly predicted a solar eclipse in 585BCE, and it is Thales' combination of empirical astronomy and theoretical speculation that lead many to identify Thales as the marking the beginning of western science as well. Thales and many of the early Greek philosophers were physicalists or materialists, holding that all that exists is matter and the void. However, many Greeks believed in immortal souls. With the decline of Greek and Roman civilization, religious approaches to understanding the universe eclipsed the ancient materialism of the Greeks.

|

|

|

Map showing Miletus from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Miletus_Bay_silting_evolution_map-en.svg |

Bust of Thales (624-546BCE) from http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/T/Thales.html |

Most of what we know about the early Greek philosophers comes from fragments of their writings and reports of

their views in the works of later writers. However, by about 400 BC philosophers like Plato (427-347BCE) and Aristotle

(400-320BCE) have begun to write works covering more or less specific areas of inquiry, and spent significant time considering investigative methodology. Both of these thinkers contributed to the two general areas of inquiry that

converge (for some) upon the explanatory schema of cognitive science: Epistemology (The Sub-discipline Exploring the Nature, Sources, & Limits of Knowledge)

Philosophy of Mind (The Sub-discipline Exploring the Nature of the Mind). Additionally, the ancient Greek philosophers considered what we know as the the sciences and

mathematics to be part of philosophy. Plato wrote the Meno1 and later theTheatetus

2, both of which prove to be influential works in epistemology. But, epistemological ruminations date back to the presocratics and continue today.

Likewise, in The

Republic, Plato introduces the tripartite division of the soul,

which has strongly influenced conceptions of the mind and its operations. According to that work the soul has three parts; the appetitive

soul, the spirit or passionate soul, the thinking or rational soul. Each element of the soul has its own characteristic desires. The good for humans consists in the subjugation of the appetitive soul to

the passionate soul, which is in turn subjugated to the rational soul. Thus, reason, emotion, and appetite become separate in Plato. One might argue that this represents the first attempt to understand the

mind in terms of constitutive elements of the mind, the functions they perform, and the relationships that emerge. In De

Anima4, Aristotle considers not only human mentality, but nature of the souls of all living creatures. Aristotle's notion of a soul involves aspects of a life-force and of mentality. Souls are essences that combine

with matter to create the specific sort of creature with specific sorts of properties and capacities. Aristotle believes that plants possess the ability to gain nourishment and reproduce themselves; animal souls have the

additional capacities of sense perception and ambulation. Only human souls have the capacity for intelligence, and only the intelligent aspects of the soul

are immortal for Aristotle. De Animaincludes discussions on methodology, the senses, and thought and reasoning.

|

|

| Plato (427-347BCE) | Aristotle (400-320BCE) |

Euclid's Geometry

One of the most under appreciated figures in shaping the western notions of

mathematics, philosophy, science, rationality and mentality is Euclid of Alexandria (325BCE-265BCE). Euclid is a Greek mathematician, who likely

received his training in geometry in Athens from students of Plato before moving to Alexandria. Euclid's best-known work, The Elements

5(approximately 300BCE), systematically and rigorously organizes geometrical knowledge in terms of indubitable axioms from which all other truths are deduced by careful proof.

The Elements also includes a treatment of basic number theory. The Elements provides readers with a comprehensive collection geometrical

theorems and proofs developed by such earlier mathematicians as Thales, Pythagoras, Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, and Menaechmus. Euclid's accomplishment in The Elements was not its content, per

se, but the organization and rigor of its presentation. Indeed, academics use Euclid's book as a text as late as the beginning of the 20th century. Euclid's rigorous axiomatization creates a model for mathematics, philosophy,

and science that remains influential today, and which often serves as a model for rational thought. Euclid's geometry proves so influential that it

influences great thinkers holding very different theories about the nature of the mind. For instance, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) is a hard-bitten physicalist. Hobbes views all things, including politics and the mind, in

terms of mechanistic operations upon physical matter. Hobbes speculates in his

Elements

of Philosophy6 that “By ratiocination [reasoning], I mean computation,” (p. 7) which Hobbes views as analogous to simple arithmetical operations upon words, where words

come to signify the objects of our experiences stored memory. As we will see below, René Descartes (1596–1650) models both his

epistemology and his scientific method on Euclid, in his books Discourse

on the Method for Conducting One's Reason Well and for Seeking Truth in the Sciences7 and Mediations

on First Philosophy8 though he famously holds that the mind is immaterial. Benedictus De Spinoza (1632–1677)

writes his famous, posthumously published work Ethics9 in axiomatic format.

In the Ethics Spinoza argues that the universe consists of one infinite, necessary, and deterministic substance that he seems to equate with both God and

nature, with both mind and body.

All these thinkers portray one’s knowledge--and rationale belief corpus--as having

(or ought to have) an organizational structure and genesis like the Euclidian geometry of The Elements. One’s knowledge all flows from careful arguments based upon premises (axioms), the

truth of which one cannot doubt. Deductive reasoning transmits the certainty and truth of one’s initial principles to all other beliefs.

Thus, the impact of Euclid consists in providing a paradigmatic instance of intellectual accomplishment, which can and does serve as an extremely influential conception of reason itself--and often all mentality--as consisting in deductive operations on statements tracing back to a set of statements held to be certain and indubitable; that is, in terms of logical operations on truth-functional representations (i.e., representations that can be true or false). One cannot underestimate the impact of this conception of reason and mentality upon our theoretical musings upon rational inquiry, reason, and the mind.

|

Euclid’s

Axioms 1.) To draw a straight

line from any point to any other. 2.) To produce a finite

straight line continuously in a straight line. 3.) To describe a circle

with any centre and distance. 4.) That all right angles

are equal to each other. 5.) That, if a straight line falling on two straight lines make the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which are the angles less than the two right angles.

|

|

| Euclid of Alexandria (325BCE-265BCE) | Electronic copy of Eucild's Elements | One of the oldest surviving fragments of Euclid's Elements, found at Oxyrhynchus and dated to circa AD 100. The diagram accompanies Book II, Proposition 5. From Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euclid |

|

|

|

| Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) |

Benedictus De Spinoza (1632–1677) |

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) |

Descartes

and Dualism

Scholars generally hold that the European Renaissance began in the Italian city state of Florence in Tuscany in the 14th century. The increase in commerce, artistic, and religious activity associated with the period from the 14th to the 17th century also brought increased scientific activity that eventually lead to what historians call the scientific revolution. Writers often associate the beginning of the scientific revolution with the publication of two important works: Nicolaus Copernicus' (1474-1543) death in 1543 marks the publication (in Germany) of his privately circulated manuscript called Commentariolus (Little Commentary) under the title De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium10 (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, published in 1543 at Nuremberg, Germany). The physician, Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), publishes his seven volume text on anatomy called De Humani Corporis Fabrica11 (On the Fabric of the Human body, published in 1555). Both of these works challenge the traditional theories and figures in their areas. Copernicus forwards the heliocentric conception the the universe in contrast to Ptolemy. Vesalius challenges many aspects of the anatomical teachings of Galen. These works and many others served to create a tradition of deterministic mechanism in science. This tradition increasingly sought to understand all phenomena in terms of universal physical laws discovered through controlled empirical experimentation, even life and the mind. The French philosopher, physicist, mathematician, anatomist René Descartes (1596-1650) painted the tension between the spiritual or immaterial world view and the mechanistic physical world view in stark contrast in his works, particularly his highly influential work Meditations on First Philosophy (1641).

Like all thinkers of the time, Descartes is dualist as well as a scientist, mathematician, and philosopher--though those endeavors are not particularly distinct at the time. He came to science rather indirectly: Descartes attends a Jesuit school located at La Flèche, France called Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand in 1607. His graduation from Henry-Le-Grand sees him earn his degree and license in Law at the University of Poitiers in 1616. Descartes joins the army of the Dutch Republic for a brief time in 1618, during which time he meets Isaac Beeckman, who reignites his interest in physics and mathematics. Descartes claims to have had dreams shortly thereafter which he interprets as a divine sign that he should found a unified science of nature based upon mathematics.

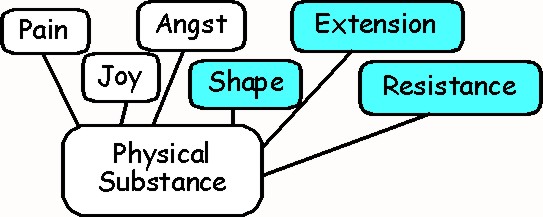

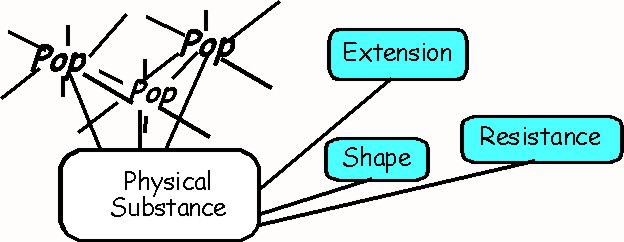

Descartes' work, Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), proves important for two reasons: (1) Because as a scientist and mathematician, he brings the goal rigorous scientific methodology and explanation to philosophical speculation regarding the mind. For instance, Descartes defines the properties of mental and physical substance, thereby further articulating the sorts of properties and causal connections that ought to underlie any explanation of the mental. Descartes defines two substances, one mental and one physical. However, unlike thinkers before him, Descartes attributes wholly different contradictory properties to these different substances. Descartes characterizes mental substance as a non-extended thinking substance that manifests mental properties like consciousness and belief. In contrast, physical substance is essentially extended, having properties of shape, size, position, and number. (2) Because of his dualist conception of the mind, and because of his scientific slant on philosophy, the Meditations--as well as his Les Passions De L'ame12 (Passions of the Soul, published in 1649) and Traite de l'homme13 (Treatise on Man, published 1664, written 1637), lay the groundwork for a switch in emphasis in the philosophy of mind. Whereas philosophic speculation regarding the mind has had a strong epistemic and functional emphasis before Descartes, emphasis turns somewhat away from epistemology and towards ontology. That is, philosophers become increasing interested in understanding if/how the mind could be physical in nature and explained through science. This interest continues today, and has led to the explicit formulation of a variety of theories regarding the nature of the mind and its relationship to the physical world. Though Descartes is a dualist, he actually furthers the mechanistic picture in that he views the body as an elaborate machine. He takes pride in his claims to have furthered mechanistic explanation of human and animal behaviors.

Ironically, it is the emphasis on science and physicalism that inspires the climatic works on the mind with a strong epistemic stance. John Locke (1632-1704) writes his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding14 (1690) to flush out the corpuscularian philosophy (essentially the hypothesis that the physical world is composed of atoms and “the void” which he learns from the great chemist Robert Boyle) with regard to the mind. Like all British Empiricists, Locke seeks to understand the mind in order to more accurately understand and theorize about the nature, limits, and sources of knowledge. David Hume (1711-1776), shares Locke’s project of understanding the nature of the mind in order to understand the nature, sources, and limits of knowledge. However, reflection upon observations--as opposed to a particular ontological picture--drive Hume's theorizing in works like, A Treatise of Human Nature 15 (1739-40) and An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding16 (1748). I come to the conclusion that empiricist theories of mind undermine one’s claim to knowledge of physical objects and causality. We both outline theories of mind that have representations and operations on those representations. Unlike Hobbes--but like Descartes--Locke's and Hume's model for representations are pictures. Locke and Hume view the mental processes underlying thought and reasoning as resulting from operations on ideas. Of particular significance, Hume views human reasoning about the experiences as resulting from operations of association rather than by deduction. For example, Hume thought that cause and effect reasoning results from habitual associations between ideas because of their constant conjunction in experience. In the In the An Abstract of a Book lately Published: Entitled A Treatise of Human Nature etc.17 (1740) tells readers that,

| Tis evident that all reasonings concerning matter of fact are founded on the relation of cause and effect, and that we can never infer the existence of one object from another, unless they be connected together, either mediately or immediately... Here is a billiard ball lying on the table, and another ball moving toward it with rapidity. They strike; and the ball which was formerly at rest now acquires a motion. This is as perfect an instance of the relation of cause and effect as any which we know, either by sensation or reflection. (¶8-9) |

The third famous British Empiricist George Berkeley (1685-1753), differs from Locke and Hume in that his work emphasizes ontological issues. Indeed, in his works, A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, Part I18 (1710) and Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous18 (1713), Berkeley argues against materialism in favor of a view called idealism, in which nothing exists but minds and their ideas.

Thus, with Berkeley we see the three major classes of theories regarding the ontological nature of the mind and body. First, materialism (or reductive materialism) holds that there is only one type of substance, material substance. The mind and all mental properties result from modifications of the same substance as all other things, i.e., the mind = the body. Second, dualism (or substance dualism) holds that there are two distinct kinds of substance, mental substance and physical substance. The mind is a mental substance, while the body is a physical substance. Finally, idealism holds that there is only one kind of substance, mental substance, and all physical objects and properties are actually ideas and their properties. As well see soon, these basic positions have many permutations.

|

|

|

| John Locke (1632-1704) | David Hume (1711-1776) | George Berkeley (1685-1753) |

|

|

|

| Thomas Reid (1710-1796) | Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) |

Interestingly, Thomas Reid (1710-1796) rigorously rejected the notion of a representational

mind at about the same time that people were reading Hume and Locke. Another sort of objection, this time to the idea of a scientific psychology comes from Immanuel Kant (1724-1804).

Kant, a physicist and philosopher, adopts the same general project of understanding the nature of the mind in order to further epistemological theorizing as Hume. However, in his book,

The Critique of Pure Reason19 (Kemp Smith's English translation 1929), Kant wants to counter Hume’s skeptical conclusions.

Kant argues that much of our knowledge flows from the innate presuppositions necessary for experience itself. Interestingly, though Kant develops and draws heavily upon a theory of

the mind in his work, he argues that a science of the mind is impossible because the field cannot be mathematicized.

The Twentieth Century

Substance Dualism

Despite Kant's skepticism, scientific psychology does begin to develop. By 20th century concerns over how best to understand and explain the mind’s physical origins drives philosophical speculation regarding the mind, supplanting the emphasis on epistemology. Additionally, concerns arising from philosophical interests in language and mathematics begin to pervade the philosophy of mind. Particularly in the second half of the twentieth century, philosophers expand upon the basic theories of mind just discussed. It is, therefore, convient to use this section to outline the standard positions in the philosophy of mind, including those that developed during this period.

As noted above, each view--reductive materialism,

dualism, and idealism constitute categories of theoretical positions in which permutations exist. For

instance, in the case of dualism philosophers commonly note three distinct positions: Descartes, held the most common position--interactive dualism. Interactive dualism holds that mental substance

and physical substance causally interact with one another. Interactive dualism might seem like the only possibility. However, two other possibilities emerge if one denies that mental and

physical substances interact. Such a denial might seem ridiculous given the apparent connection between mental phenomena and physical phenomena. For

instance, if someone steps on your foot, a physical phenomenon, you will likely experience a feeling of discomfort in your foot, a mental phenomenon. However, Descartes' clarity and rigor in differentiating mental and

physical substance, ironically, raises a significant challenge to interactionism.

Recall that mental substance is essentially non-spatial, lacking all physical properties.

Likewise, physical substance is essentially spatial, lacking all mental properties. If the mind and the body are fundamentally different sorts of stuff, one must ask, "How could these

two substances possibly causal interact with one another?" For that matter, given that the mind is non-spatial, where could they possibly causally interact? It seems indubitable that the mind and the body interact with one another,

and so interactive dualism must explain how such causal interaction could possibly occur. Philosophers have articulated many difficulties with interactive dualism, but most agree that the difficulties

with causal interaction have to rank very high. In addition to difficulties with the very idea of inter-substance causation, another serious difficulty emerges almost immediately from dualistic

interactionism. In a mechanistic, deterministic physical science, all changes in the physical world should be explicable (at least in principle) by universally applicable purely mechanistic,

deterministic physical laws. But, if mental substances and causal substances causally interact, mental causation renders universal purely mechanistic, deterministic physical laws impossible. Mental to physical causation will always

fall outside purely physical laws.

One possible solution to this last worry involves denying interactionism--at least

in one direction. Epiphenomenalism is the view that changes in physical substances can causal mental phenomena, but that changes in mental substances cannot cause changes in physical substances or

their properties. Thus, one can still hold that some causal connections exist between the mental and the physical, but mental causation will never violate universally applicable purely mechanistic, deterministic physical laws. While

epiphenomenalism might allow for deterministic physical laws, it implies that mental phenomena never cause physical phenomena--violating the seeming obvious nature of mind-body interactions. Worse still, epiphenomenalism must

explain why causation only runs from the physical to the mental, and not vice versa.

The second dualist solution to the problem of interaction also denies interactions. Parallelism is the view that mental and physical substances only appear to causally interact. Instead of causal interaction, mental and physical changes merely mirror one another, creating the illusion of interaction. One might find one anti-interactionism less plausible than the next. However, considering the difference between causation and correlation might make parallelism seem somewhat more plausible. The time on my watch may always correlate with the time on your watch, but no one supposes that our watches causally interact. One can summarize the various substance dualistic positions in the following table:

|

Possible Substance Dualisms |

||

| Mental to Physcial Causation | Physical to Mental Causation | |

| Interactionism | YES | YES |

| Epiphenomenalism (mental) | NO | YES |

| Epiphenomenalism (physical) | YES | NO |

| Parallelism | NO | NO |

|

|

||

|

Diagram depicting the position called substance dualism (interactionism) according to which minds and physical bodies are ontologically distinct. They are different types of substances, each of which can have distinct types of properties. Here conveniently yet inaccurately modeled by bubbles. |

||

Physicalism

Substance Dualists seem to face a choice between difficult options: Epiphenomenalism and parallelism imply that the seeming robust causal interaction between mental and bodily phenomena is illusory. Interactionists, in contrast, face the daunting challenge of explaining how such different type of substances having such different properties can causally interact. Physicalism might seem to have an obvious advantage in that it does not suppose that the mental and the physical are radically different. However, this very strength presents the physicalist with a challenge. Specifically, mental properties do seem different from other sorts of physical properties. Indeed, many people find the idea that mental properties are just physical, mechanistic properties intuitively unpalitable. For instance, every physical object has mass, but only animals seem to be candidates for conscious qualitative experiences. Why, one might well ask, are only some physical objects candidates for mental properties? Similarly, mental properties seem qualitatively different from physical properties. How do mental properties arise from physical properties and processes?

Logical Behaviorism

The first answer to these sorts of questions was simply that mental properties were just physical properties. Such views are expressed by, for example, Aristotle4 when he claims that,

|

...their definitions ought to correspond, e.g. anger should be defined as a certain mode of movement of such and such a body (or part or faculty of a body) by this or that cause and for this or that end. (Book I, Part I, ¶6) |

However, most historical accounts trace type-type indentity theory to two papers "Is Consciousness a Brain Process?"20 by U.T. Place (1956) and "The 'Mental' and the 'Physical'"21 by Herbert Feigl (1958). The first attempt to systematically address the difficulties for physicalism is a position called Logical or Analytical Behaviorism. In general, most historians cite Gilbert Ryle's book, The Concept of Mind22 (1949), then Hempel's "The Logical Analysis of Psychology"23 (1935,1949). However, Hempel's article is published, though in French, over 14 years earlier. Both works are important because they share a common shift of emphasis that has continued to shape thinking about the mind in philosophy. Both Ryle and Hempel seek to defuse the seeming difficulties in understanding how mental properties arise from or are identical to physical properties by arguing that the meanings of mental terms are exhausted by behavioral terms. Hempel tell readers,23

|

All psychological statements which are meaningful, that is to say, which are in principle verifiable, are translatable into statements that do not involve psychological concepts, but only the concepts of physics. The statements of psychology are consequently physicalistic statements. (p.18) |

Similarly, Ryle asserts,22

|

In this chapter I try to show that when we describe people as exercising qualities of mind, we are not referring to occult episodes of which their overt acts and utterances are effects; we are referring to those overt acts and utterances themselves. (p.25) |

|

|

|

|

| Gillbert Ryle (1900-1976) |

Carl Gustav Hempel (1905-1997) |

Roderick Chisholm (1916-1999) |

Hilary Putnam (1926- ) |

While Hempel aims primarily to address scientific and ontological issues, Ryle sees his work in a different light. Instead, Ryle tries to provide an analysis of the concepts of ordinary language. In both cases, however, the seeming difficulties associated with the equation of mental properties and physical properties are traced to an improper understanding of the true meanings of mental terms. Ryle asserts that,22

This book offers what may with reservations be described as theory of mind. But it does not give new information about minds. We possess already a wealth of information about minds, information which is neither derived from, nor upset by, the arguments of philosophers. The philosophical arguments which constitute this book are intended not to increase what we know about minds, but to rectify the logical geography of the knowledge which we already possess. (p.7) |

Additonally, Ryle's emphasis on intelligent behavior marks a differentiation between mental

properties that has come to be standard in the philosophy of mind, and which allows for the initial explanatory focus of cognitive science on cognition. Specifically, philosophers differentiate between mental properties and

states that are strongly (or even definitively) phenomenal in nature, called qualia or qualitative mental states, and mental properties

or states that are primarily (or even definitively) intentional, called intentional states or propositional attitudes. Examples of the former (qualia) include pains, itches, seeing red,

anger etc.. Examples of the latter (intentional states) include beliefs and desires. Intentional states may have some phenomenal aspects, but they are

importantantly representational--those states are about objects, properties, and/or events in the world.

Logical behaviorists like Hempel seek to build upon real progress by experimentalist

like Pavlov, Watson, Tolman, and Skinner as well as by scientists across a wide sawth of the sciences. They view the explosion of scientific progress from the beginnings of the scientific

revolution to the middle twentieth century as deriving primarily from tying theories and theoretical terms to rigorous empirical measurement and experimentation. However, logical behaviorism faces three significant difficulties.

First, the meanings of many mental terms seem essentially tied to qualitative subjective experience as opposed to the behaviors they cause. Thus, many people find the awfulness of pain essential to being in pain,

but few find verbal demonstrations essential to being in pain. A person paralized by curare will not exhibit the normal behavioral effects of pain when stabbed in the arm. However,

it seems impropable to suppose that such a person feels no pain. Likewise, actors really do suffer for their art according to logical behaviorists. Second, many mental properties such as aibohphobia (a fear of palindromes),

ankylophobia (fear of stiff or immobile joints) and malaise (a vague feeling of discomfort, one cannot precisely identify, but which is often desdcribed as a sense that things are "just not right.") seem not to have any definitive

set of behvorial effects. Third, mental terms do not operate, for the most part, in isolation from one another. Rather, the connections between the typical behavioral causes and typical

behavioral effects--even for those mental terms that appear to have more or less criterial behavioral causes and effects--are mediated by the interactions mental states with other mental states. For

instance, the causes and effects of your belief that this text is remarkably dry cannot be determined in isolation. If you love dry and boring texts, you may read all night. If you are hungry, your belief may result in your getting a chocolate

bar.

Theorists are exploring the general difficulties facing approaches like Ryle's and

Hemple's in the technical literature even before Ryle publishes The Concept of Mind. However, Putnam's "Psychological Concepts, Explication, and Ordinary Language"24 (1957) and Chisholm's "Intentionality and the Theory of Signs"25 (1952) served to make explicit and popularize the implications of these technical problems for logical behaviorism.

Type-Type Reductionism

As noted above, historians generally credit the British philosopher and

psychologist U.T. Place (1924-2000) and the Austrian philosopher Herbert Feigl (1902-1988) as the source of the modern identity version of physicalism. Place's colleague, J.J.C. Smart (1920- ) also adopts this position. The

identity theorists' motivations stem in large part from (and build upon) the difficulties with logical behaviorism. For instance, Place tells readers,20

|

The view that there exists a separate class of events, mental events, which cannot be described in terms of the concepts employed by the physical sciences no longer, commands the universal and unquestioning acceptance amongst philosophers and psychologists which it once did. Modern physicalism, however, unlike the materialism of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, is behaviouristic. Consciousness on this view is either a special type of behaviour, 'sampling' or 'running-back-and-forth' behaviour as Tolman (1932,p. 206) has it, or a disposition to behave in a certain way, an itch for example being a temporary propensity to scratch. In the case of cognitive concepts like 'knowing', 'believing', 'understanding', 'remembering' and volitional concepts like 'wanting' and 'intending', there can be little doubt, I think, that an analysis in terms of dispositions to behave (Wittgenstein, 1953; Ryle, 1949) is fundamentally sound. On the other hand, there would seem to be an intractable residue of concepts clustering around the notions of consciousness, experience, sensation and mental imagery, where some sort of inner process story is unavoidable (Place, 1954). It is possible, of course, that a satisfactory behaviouristic account of this conceptual residuum will ultimately be found. For our present purposes, however, I shall assume that this cannot be done and that statements about pains and twinges, about how things look, sound and feel, about things dreamed of or pictured in the mind's eye, are statements referring to events and processes which are in some sense private or internal to the individual of whom they are predicated. (p.44) |

Two central ideas define type-type identity: First, Place and Feigl hold that

behavioristic and identity analyses of mental terms do not exhaust the meaning of mental terms in ordinary language. That is, the new definitions of mental terms are not analytic--they

do not capture the individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions thought to dictate the meanings of ordinary terms. Place and Feigl hold that mental and physical terms pick out classes or

kinds of things in virtue of their meanings, and that a significant part of the meaning of ordinary mental terms (as well as of the identity theorists new analyses of those terms) is synthetic--i.e., going

beyond the definitional meaning, usually as a result of experience. Specifically, they hold that the various behavioral associations between mental terms and physical/bodily terms serve to provide an initial description

of a physical (brain) state. One can modify the intial behavioral descriptions, to the entent necessary, as a result of experience. Such descriptions ultimately determine the physical state that corresponds to the mental state.

The identification of the physical state with the mental state constitutes a synthetic discovery.

|

|

|

|

|

Herbert Feigl (1902-1988) |

U.T. Place (1924-2000) | John Jamieson Carswell "Jack" Smart (1920- ) |

|

|

||

|

Diagram depicting Type-Type Identity Theory. Type-type theorists claim that there is only physical substance. Mental properties exist, but are type-identical to physical properties. The identity is made by using the physical behavioral associations between mental and physical terms to identify the physical state type corresponding to the mental state type. |

||

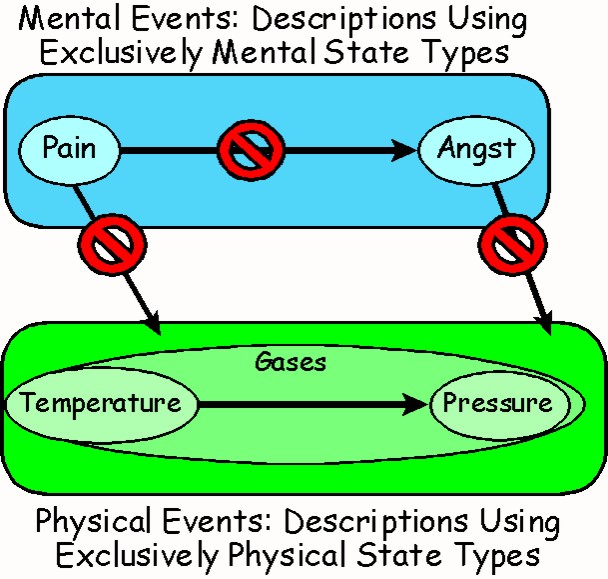

In 1970, Donald Davidson (1917-2003) proposes a new version of identity physicalism. Davidson starts his chapter, "Mental Events,"26 by stating his motivation for the view,

|

Mental events such as perceivings, rememberings, decisions, and actions resist capture in the nomological net of physical theory. .... I start from the assumption that both the causal dependence and the anomalousness of mental events are undeniable facts. My aim is therefore to explain, in the face of apparent difficulties, how this can be. (p.138) |

By

nomolgical Davidson simply means law-like, and by anomolousness

Davidson means not falling under exceptionless universal laws.

Davidson thinks that the failure to find simple type-type identifications

suggested by theorists like Smart, Plcae, and Fiegl and the failure for

psychology and sociology to generate universal exceptionless laws warrants a

reconsideration of the type identity theory.

In the quote above Davidson tells readers that he takes the anomalousness

of the mental as an undeniable fact.

However, he does offer a reason for that anomalousness--attributions of

mental terms are guided primarily by providing an understanding of the person as

a rational agent.

This emphasis on rational understanding can, and Davidson suggests does,

often trump ascriptions that would support universal and exceptionless laws.

Davidson holds that the physical world has proven to be a mechanistic and

deterministic by the dramatic success of sciences like physics.

Davidson understands these sciences as producing exceptionless universal

laws.

These laws are formulated using exclusively physicalistic descriptions,

and yeild a closed, complete deductive system.

That is, given a complete physicalistic description of some state of the

world, called an event, a scientist can, at least in principle, use the

exceptionless laws of the relevant science to deduce how the causal world will

unfold by deducing the resulting event, i.e., the exclusively physicalistic

description of the world resulting from the prior event.

Davidson felt that psychological generalizations could also be used to

explain and predict by relating mental events, descriptions of some state of the

world using exclusively mentalistic terms.

However, mental events were not related to one another using

exceptionless universal mental laws.

Hence, psychological laws do not form a closed, complete deuctive system.

Thus, Davidson concludes that there cannot be exceptionless universal "bridge-laws"--laws

that relate mental descriptions of states of the world, mental events, to

physical descriptions of states of the world, physical events.

Though the argument seems complex, it's actually pretty straightforward.

Physical laws are universal and exceptionless.

Mental laws are neither universal nor exceptionless.

But, if there were universal and exceptionless laws linking mental and

physical events, then they would provide a basis for universal exceptionless

mental laws.

Hence, there can be no universal and exceptionless bridge laws.

|

|

|

Donald Herbert Davidson

|

Diagram of the relationships in Davidson's argument for anomolous monist or token-token identity theorist. Individual mental events are identical to some or other particular physical event. However, anomolous monists deny the mental event types (kinds) are identical to physical event types (kinds). |

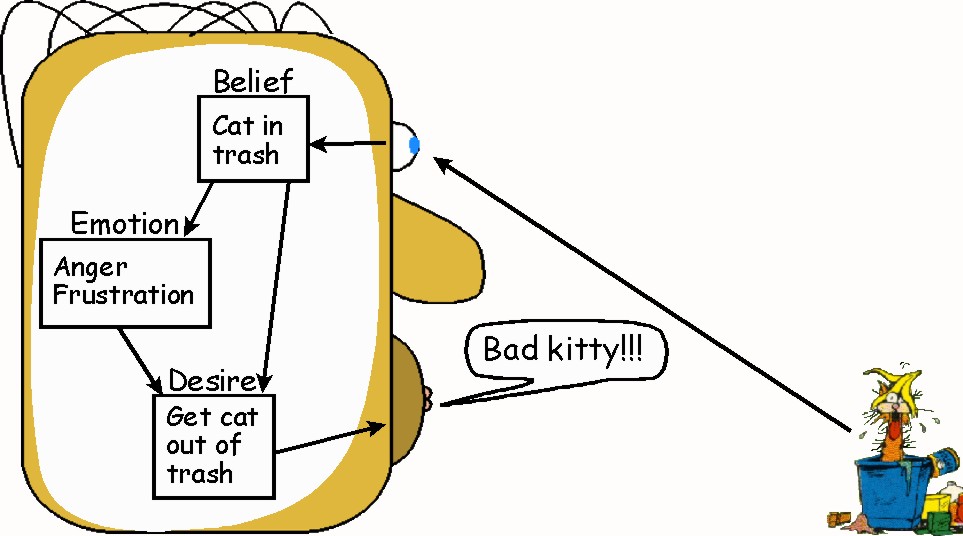

Functionalism

Not all philosophers see the failure to discover the mental type to physical type

identities and robust psychological laws predicted by type-type identity theory, as the central difficulty for theorists like Feigl and Place. Putnam didn't suppose that psychology must formulate universal

exceptionless laws. Instead, Putnam held that psychological laws would take the form of statistical gneralizations. In two classic articles, "

Minds and Machines"27 (1960) and

“Psychological Predicates28 (1967) (later published as The Nature of Mental States),

Hilary Putnam (1926- ) formulates a slightly different solution to the problems that motivate Fiegl and Place called fuctionalism. As noted earlier, philosophers like Plato and Aristotle seem to advocate

theories that are roughly characterized as functionalist. However, Putnam puts the modern face on functionalims. Putnam suggests that mental terms like pain and belief are not properly

identified with some state that causes the behavioral indicators. Rather these mental terms refer to the functions that pain, belief, etc. play in the overall functioning of the organism. Specifically, Putnam suggested that physical

causes of mental states (inputs), their causal relationships to other mental states, and the effects of mental states of physical states (outputs) served to definitively characterize

mental states. Putnam identifies mental states with their functional characterizations, in part because, he argues, systems may come to have different states from a physiological

perspective that have the same functional characterization. Such states, Putnam suggests, would be instances of the same psychological type, but instances of different physiological types. For example, if you believe that lobsters feel

pain, you won't find type identity theory very satisfying becuase lobsters lack a centralized nervous system, and hence, lack the structures associated with pains in humans. This idea came to be known as multiple

realizability. Ned Block (1942- ) and Jerry Fodor (1935- ) publish "What

Psychological States are Not"29 in 1972, further articulating and defending functionalist theory. Even as Putnam articulates a synthetic, empirical functionalism, D. M.

Armstrong (1926- ) published his A Materialistic Theory of the Mind30. Like Putnam, Armstrong argued that mental states were best characterized by descriptions incorporating physical causes of mental states

(inputs), their causal relationships to other mental states, and the effects of mental states of physical states (outputs). However, unlike Putnam, Armstrong views these descriptions as strict analyses of the

concepts of our ordinary language terms that give the individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions that the terms meaning. Finally, like Place, Armstrong viewed these descriptions as picking out

the physical state that corresponded to the mental state.

|

|

|

|

| Hilary Putnam (1926- ) | D. M. Armstrong (1926- ) | Jerry Fodor (1935- ) | Ned Block (1942- ) |

|

|||

|

Diagram depicting the relationships important for characterizing mental states according to functionalism. These theorists hold that a mental state is the type of state it is in virtue of its place in one’s overall cognitive economy (one’s causal nexus as described by an accurate theory), specifically the physical causes of mental states (inputs), their causal relationships to other mental states, and the effects of mental states of physical states (outputs). |

|||

Computationalism

The connection between functionalism and computation as well as computers traces back to Putnam's early formulations.

However, starting in the late 1970s philosophers converge upon the basic explanatory schema of the CTC/RTI both as a theory of cognition and cognitive states, and as a theory of explanation and

explanatory methodology. Work by Ned Block (1942- ) ["Introduction: What is Functionalism"31 and "Troubles with Functionalism"32], Robert Cummins (1948- )

["Functional Analysis"33 and The Nature of Psychological Explanation34],

Dan Dennett (1942- ) [Brainstorms35], Jerry Fodor (1935- ) ["Special

Sciences (Or: The Disunity of Science as a Working Hypothesis)"36 The Language of Thought37], and John Haugeland (1945- )

["Semantic Engines"38 and Artificial Intelligence: The Very Idea

39] further articulate the structure of explanations in Cognitive Science. The resulting picture is beautifully articulated in their work. The last few

of these introductory lectures, outlines the salient features of this picture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ned Block (1942- ) |

Robert Cummins (1953- ) |

Daniel Dennett (1942- ) |

Jerry Fodor (1935- ) |

John Haugeland (1945- ) |

Property Dualism

As noted in the introduction, the explanatory schema and methodology outlined in these introductory lectures does not have homogeneous acceptance across all researchers in all the core disciplines of cognitive science. Two other views emerge in the late 1970s and 1980s. One position that emerges stems from the difficulties faced by functionalism to capture the qualitative aspects of consciousness, also called qualia. Thomas Nagel (1937- ) publishes "What it is like to be a Bat?,"40. Frank Jackson (1943- ) publishes "What Mary Didn't Know,"41 and David Chalmers (1966- ) publishes "Absent Qualia, Fading Qualia, Dancing Qualia"42 and The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory.43 Each of these works suggest, for different reasons than Armstrong, that some if not all mental states are not physical states as traditionally understood. Nagel and Chalmers both take a page from Spinoza, and suggest that the notion of physical substance should be expanded to allow for both the traditional physical properties and mental properties. This view is known as property dualism.

|

|

|

| Thomas Nagel (1937- ) | Frank Jackson (1943- ) | David Chalmers (1966- ) |

|

||

|

Diagram depicting the relationship between mental and physical properties according to property dualism. In such theories all possible properties, mental and physical, are properties of a single physical-like substance. However, mental and physical properties are irreducible to one another. Generally, such views seek to preserve the special character of mental properties, holding that scientific progress requires some new conceptual and/or scientific reconceptualization and methodological revolution. |

||

Eliminative Materialism

The final view we'll consider in this lecture, eliminative materialism has a amorphous history. The basic idea behind the view had been in the air for a long time. Historians often attribute it to James Cornman's " On the Elimination of 'Sensations' and Sensations"44 (1968). Cornman himself attributes it to WVO Quine's Word and Object45(1960). William Lycan and George Pappas attribute it to Richard Rorty's "Mind-Body Indentity, Privacy and Categories"46(1965). However, few doubt that eliminative materialism rose to prominence and came to be associated with the University of California, San Diego and three philosophers who spent the early 1980s there. It is these three thinkers as well as Daniel Dennett that gave the view its modern formulation, and its most rigorous defense. As the seventies end and the eighties begin, Paul Churchland, Patricia Churchland, Daniel Dennett, and Stephen Stich publish papers outlining and defending the view that our ordinary mental terms constitute a psychological theory--folk psychology. Eliminativists hold that our theoretical terms pick-out (or fail to pick-out) real objects or properties in virtue of the role these terms play in our theories. In other words, theoretical terms pick-out (or fail to pick-out) real-world objects in virtue of that the theory asserts about those objects. For instance, Phlogiston theory tells us that flammable objects contain phlogiston, the fire stuff. Object combustion, according to the theory is just the process of phlogiston leaving the object. So, the phlogiston theory picks out a real-world object, just in case there is something in the real world that satisfies the properties and relations attributed to phlogiston by the theory. In the case of phlogiston, scientists discover that the net byproducts of combustion have a greater mass than the original material. This finding, among others, suggests that there is no phlogiston, i.e., there is no real world object that plays the role of leaving a combustible material when it burns. Similarly, if a theory proves inadequate to explain phenomena, then we ought to suppose that the theory is false, and the objects it posits do not exist.

Folk psychology, the eliminativists argue, is both explanatorily

inadequate, and taken as whole, radically false about the states

and properties of the mind.

For instance, consider the following prima facie inadequacies of our

ordinary folk psychological understanding of our minds: Nothing about our

ordinary notion of consciousness explains why we have to spend approximately

eight hours a day unconscious. Nor does the folk psychological concept of

consciousness explain what happens when we go from being conscious to being

unconscious, or why we can't simply will ourselves to be unconscious.

Likewise, folk psychology proves woefully inadequate to explain why people

develop illnesses like schizophrenia. As Paul Churchland observes:47

| In sum, the most central things about us remain entirely mysterious from within folk psychology. And the defects noted cannot be blamed on inadequate time allowed for their correction, for folk psychology has enjoyed no significant changes or advances in well over 2,000 years, despite its manifest failures. (p.46) |

Similarly,

Dennett48 notes that our ordinary notion of pain as a unified

experience looks prima facie false when one notices that the painfulness and the

adverseness or awfulness of pain can, and in many cases do, appear in isolation

from one another. For example, people given morphine prior to their

operations often report feeling the painful sensations without the adverse or

awful aspects when prodded by the surgeon. Similarly, the awfulness of

pain can be diminshed by concentrating on the painfulness aspect of the

qualitative experience.

As a result, eliminativists argue, mental properties as conceived by our folk psychology do not actually exist. This position has come to be known as eliminative materialism. Daniel Dennett's "Why You Can't Make a Computer that Feels Pain,"48(1978) and Consciousness Explained 49(1991), Paul Churchland's " Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes"50(1981), " Reduction, Qualia, and the Direct Introspection of Brain States,"51(1985), Stephen Stich's From Folk Psychology to Cognitive Science: The Case Against Belief 52(1982), and Patricia Churchland's Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain53 (1986) are perhaps the best known and most definitive statements of the view. It is important to note that the contemporary statement of the view does not deny the existence of any kind of mental states or properties. Rather, it denies the existence of the mental states and properties found in and understood through our ordinary concepts. Thus, while Paul Churchland and Daniel Dennett deny that pains exist, they do not deny that we experience adverse sensations when stuck with a pin. They deny that a state or property exists that satisfies the description ingrained within our ordinary mental concepts of the typical causes and effects of pains.

|

|

|

| Patricia Churchland (1943- ) | Paul Churchland (1942- ) | Stephen Stich (1943- ) |

|

||

|

Diagram depicting the eliminative materialist view that ordinary mental terms constitute a folk psychology that is radically false about the nature and properties of the mind. As a result, mental properties as conceived in our folk psychology do not exist. |

||

A

final point to note with regard to eliminative materialists; the staunchest

advocates of eliminative materialism are also among the most influential

architects of the contemporary understanding of computationalism. In other

words, denying that an adequate explanation of cognition and cognitive

capacities will include our ordinary folk concepts (together with their alleged

referents) is consistent with asserting that such explanations will take the

form of computational/representational theories.

In the next lecture we turn to the historical development of physiology. One might think that physiology marks a detour out of the core disciplines of cognitive science. However, physiology makes two significant connections in the history of cognitive science. First, psychology has two parent disciplines; philosophy and physiology. Philosophy introduces the “big questions” regarding the nature and operations of the mind. Physiology--particularly the early physiology of the nervous system--marks the beginnings, not only of neuroscience, but also of the introduction of experimental methodology to the study of the mind. Second, neuroscience develops out of physiology.

Sources

|

1. |

Plato. Meno (380 BCE). |

|

2. |

Plato. Theaetetus (360 BCE). |

| 3. |

Plato.

The Republic (360BCE). |

| 4. |

Aristotle.

On the Soul (350 BCE). |

| 5. |

Euclid.

The Elements of Euclid (William Pickering, London, 1847 (300 BCE)). |

| 6. | Hobbes, T. (ed. Calkins, M.W.) (Open Court Publishing, Chicago, 1905). |

| 7. |

Descartes,

R. Discourse on the Method for Conducting One's Reason Well and for

Seeking Truth in the Sciences (Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis,

IN, 1998). |

| 8. |

Descartes,

R. Mediations on First Philosophy With Selections from the Objections and

REplies (ed. Cottingham, J.) (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

1996). |

| 9. |

Spinoza,

B.D. Ethics (Wordswoth Editions, Hertfordshire, 2001). |

| 10. |

Copernici,

N. De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Wikipedia.org, 2007). |

| 11. |

Vesalii,

A. De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body)

(Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 1543). |

| 12. |

Descartes,

R. Les Passions De L'ame (Passions of the Soul) (ed. Voss, S.H.) (Hackett,

Indianapolis, IN, 1989). |

| 13. |

Descartes,

R. Traite de l'homme (Treatise on Man) (ed. Hall, T.S.) (Prometheus Books,

Amherst. NY, 2003). |

| 14. |

Locke,

J. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (ed. Nidditch, P.H.) (Oxford

University Press, Oxford, 1979). |

| 15. |

Hume,

D. A Treatise of Human Nature (ed. Levine, M.P.) (Barnes & Noble, New

York, NY, 2005). |

| 16. |

Hume,

D. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (ed. Buckle, S.) (Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, 2007). |

| 17. |

Hume,

D. An Abstract of a Book lately Published: Entitled A Treatise of Human

Nature etc. (1740). |

| 18. |

Berkeley, G. A Treatise Concerning The Principles Of Human Knowledge: Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous (ed. Warnock, G.J.) (Open Court Publishing, New York, NY, 1979). |

| 19. |

Kant,

E. Critque of Pure Reason (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY, 2003). |

| 20. |

Place,

U.T. Is Consciousness a Brain Process? British

Journal of Psychology 47,

44-50 (1956). |

| 21. |

Feigl,

H. in Concepts, Theories and the Mind-Body Problem, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Studies in the Philosophy of Science (eds. Feigl, H., Scriven, M. &

Maxwell, G.) University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN, 1958). |

| 22. |

Ryle,

G. The Concept of Mind (New York, NY, 1949). |

| 23. | Hempel, C.G. in Readings in the Philosophy of Psychology (ed. Block, N.) (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1980). |

| 24. |

Putnam,

H. Psychological Concepts, Explication, and Ordinary Language. The

Journal of Philosophy 54,

94-100 (1957). |

| 25. |

Chisholm,

R. Intentionality and the Theory of Signs. Philosophical

Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic 3,

56-63 (1952). |

| 26. |

Davidson,

D. in Essays on Actions and Events (eds. Vermazen, B. & Hintikka,

M.B.) (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1980). |

| 27. |

Putnam,

H. in Dimensions of Mind (ed. Hook, S.) 148-180 (New York University

Press, New York, NY, 1960). |

| 28. |

Putnam,

H. in Art, Mind and Religion (eds. Capitan, W.H. & Merrill, D.D.)

37-48 (University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA, 1967). |

| 29. |

Block,

N. & Fodor, J. What Psychological States Are Not. Philosophical

Review 81, 159-181 (1972). |

| 30. |

Armstrong,

D.M. A Materialistic Theory of the Mind (Routledge & K. Paul, London, 1968). |

| 31. |

Block,

N. "Introduction: What is functionalism," in Readings in the Philosophy of Psychology (ed. Block, N.) 268-305

(MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1980). |

| 32. |

Block,

N. "Troubles With Functionalism," in Readings in the Philosophy of Psychology (ed. Block, N.) 171-184

(MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1980). |

| 33. | Cummins, R. "Functional Analysis." The Journal of Philosophy 72, 741-765 (1975). |

| 34. | Cummins, R. The Nature of Psychological Explanation (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1985). |

| 35. | Dennett, D. Brainstorms. (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1978). |

| 36. |

Fodor, J. Special Sciences (Or: The Disunity of Science as a Working Hypothesis). Synthese: An International Journal for Epistemology, Methodology and Philosophy ofScience 28, 97-115 (1974). |

| 37. |

Fodor,

J. The Language of Thought (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA,

1975). |

| 38. |

Haugeland,

J. in Mind Design: Philosophy, Psychology, and Artificial Intelligence

(ed. Haugeland, J.) (1981). |

| 39. |

Haugeland,

J. Artificial Intelligence: The Very Idea (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA,

1985). |

| 40. |

Nagel,

T. What is it like to be a Bat. Philosophical

Review 83, 435-450 (1974). |

| 41. |

Jackson,

F. What Mary Didn't Know. Journal of

Philosophy 83, 291-293

(1986). |

| 42. |

Chalmers,

D. in Conscious Experience (ed. Metzinger, T.) 309-330 (Imprint Academic

Throverton, 1996). |

| 43. |

Chalmers,

D. The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory (Oxford

University Press, Oxford, 1996). |

| 44. |

Cornman,

J., W. On the Elimination of 'Sensations' and Sensations. The

Review of Metaphysics 22,

15-35 (1968). |

| 45. | Quine, W.V.N. Word and Object (MIT Press, New York, NY, 1960). |

| 46. |

Rorty,

R. Mind-Body Indentity, Privacy and Categories. The

Review of Metaphysics 19,

24-54 (1965). |

| 47. |

Dennett,

D. "Why You Can't Make a Computer that Feels Pain". Synthese:

An International Journal for Epistemology, Methodology and Philosophy of

Science 38, 415-456 (1978). |

| 48. |

Dennett,

D. Consciousness Explained (Little, Brown, and London, Boston, MA, 1991). |

| 49. | Churchland, P.M. Matter and Consciousness (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1984). |

| 50. |

Churchland,

P.M. Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes. Journal of Philosophy 78,

67-90 (1981). |

| 51. |

Churchland,

P.M. Reduction, Qualia, and the Direct Introspection of Brain States. Journal of Philosophy 82,

8-28 (1985). |

| 52. |

Stich,

S. From Folk Psychology to Cognitive Science: The Case Against Belief (MIT

Press, Cambridge, MA, 1983). |

| 53. | Churchland, P. Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain (1986). |