Psychology’s Movement

Toward Cognitive Science

The progression between psychological schools of thought

in this brief history emphasizes three trends: First, psychology progresses through the development, evaluation, and

integration of experimental methods into psychology. Second, psychological schools of thought move

from emphasizing the conscious, qualitative aspects of mind and mental

processes to emphasizing characterizations of the mind and mental processes in

terms of informational processing. Third,

psychologists develop and adapt experimental techniques in order to more

reliably explore those elements of their information processing models not

directly observable by experimenters. The

development of experimental methodologies, the refinement of animal and other

models, increased knowledge of human mentality, development, and physiology,

and the development of technical ideas such as information and computation

ultimately coalesce, allowing for the conceptual framing of cognitive phenomena

as well as its systematic experimental investigation.

In our

discussion the development of physiology, I emphasize

that physiology introduces a strong empirical and experimental emphasis to psychology. Indeed, many early psychologists receive their training from physiologists and anatomists. Consistent with that idea, I begin the

discussion of the development of psychology towards cognitive science with the development of an experimental technique that has proven quite central to psychology—reaction

time.

Reaction

Times and Mental Chronology

Reaction

time is the time it takes from the initial presentation of stimulus until

the subject reacts. For instance, the time between a light flashing and a

subject pressing a button would be that subjects reaction time for that

stimulus-response pairing. Reaction time measurement begins with Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784-1846), a German astronomer and Gymnasium drop-out. The controversy regarding disparate observations of transit times

between the astronomers Maskelyne and Kinnebrook,

and later between Enckes and Gauss intrigues Bessel. Transit times are

measurements of how long it takes stars to cross hairlines in

telescopic observations, indicating the time it takes the star to pass over the meridian of the

observatory. Astronomers use transit times for a star to determine the coordinates of the star.

Precise measurements of star coordinates are becoming increasingly important in

the 1700s and 1800s, both for the astronomers and also because nautical tables of the time rely upon coordinate information for stars.

Twenty years after the original dispute (1821), Bessel both analyzes the observations of different astronomers and performs

the simple

experiment of comparing observations between observers using the same equipment.

Bessel determines that skilled astronomers will vary consistently in their observations of

transit times. As a result, Bessel introduces the notion of an “involuntary constant difference,” in describing his findings in the preface to the eighth volume of his

Astronomische Beobachtungen1(1823).

In astronomy, the phenomena now commonly goes under the name

introduced by John Pond (1767–1836) in 19332, as the “personal

equation.” It is not an exaggeration to describe this work as the first experimental quantitative measurement of

reaction time, and it eventually results in the first attempt to control both

for reaction time and also for individual differences in scientific

observation. The German physiologist, Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (1821-1894)

published his “On the Rate of Transmission of the Nerve Impulse”3 in 1850. The Swiss astronomer Adolph Hirsch (1830-1901)

publishes his “On the Speed of Mental Processes,” (1862) in which he 4

|

…was

the first (1) to use Hipp's chronoscope in scientific literature, (2) to study

reaction time in connection to psychological interest, and (3) to study

velocity of conduction in humans with appropriate techniques. Using Hipp apparatus, Hirsch showed differences

in time for manual response (1) to auditory, visual, and tactile stimulation; (2) between observers; (3) in Hirsch's own results when fresh and when

fatigued; (4) according to the locus of tactile stimulation and the hand used for response; and (5) according to whether the stimulus was expected or

unexpected. Moreover, observations made on one of his colleagues relate the conduction speed in nerves, from which he

concludes that the differences in reaction time were due to the varying lengths of nerves. The speed of transmission in sensory nerves was evaluated by Hirsch

at about 34 m/s. (p.261) |

Franciscus Cornelis Donders (1818-1889) is usually cited as the first researcher

to use differences in human reaction time to infer differences in cognitive processing

time. Building on the work of his

graduate student, Johan Jacob De Jaager,5 and with an

awareness of earlier work by Helmholtz and Hirsch, Donders uses the same

subtraction method employed by Helmholtz, to make inferences about the times of

various mental processes. In 1868, Donders publishes “On the Speed of Mental Processes,”6 in which he shows that a simple reaction time

is shorter than a recognition reaction time, and that the choice reaction time

is longest of all. Using these times, Donders makes inferences as to the speed of mental processes through

subtraction: recognition = (recognition reaction time - simple reaction time).

Donders' results are an instance of mental

chronometry, i.e., the study of the relative speed and temporal

sequencing of mental process under some specified set of conditions. The ideas of subtraction, mental chronometry,

and reaction time are now part of the central methodological framework of cognitive psychology.

The next experimental technique, introspection, has a less venerable history.

|

|

|

|

|

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784-1846)

|

Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894)

|

Franciscus Cornelis Donders (1818-1889)

|

|

|

|

|

A chronoscope built by the Swiss inventor

Matthias Hipp in 1888. Early psychological

and physiological researchers used chronoscopes to measure reaction times in

their experiments. This chronoscope is

accurate to 1/1000th of a second.

|

Diagram illustrating the subtraction

technique. A researcher takes two

tasks that differ only by one component task.

In this case, the first task is a simple reaction task composed of a

perception task and a motor response task.

The second task is a discrimination task composed of a perception

task, a motor response task, and the discrimination task. The researcher determines the mean time for

subjects to complete each task. Subtraction

of the simple reaction time from the discrimination task time to yield the

time of the discrimination task alone.

|

Introspection and

Introspection-Based Psychologies

The technique of introspection

enters psychology through the work of Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt, (1832-1920) a

German physician, psychologist, physiologist, and university professor. Wundt, Titchener, and Brentano are often

portrayed together under the title of introspectionist psychology. However, as we will see, these theorists differ

significantly in their theoretical perspectives as well as their use of

introspection.

|

|

|

|

|

Wilhelm

Wundt (1832-1920)

|

Edward

Titchener (1867-1927)

|

Franz Brentano

(1838-1917)

|

Introspectionist

Psychology: Voluntarism

Wundt creates the first laboratory explicitly dedicated to psychological research (as opposed to

labs for teaching demonstrations) at the University of Leipzig

in 1879. He also begins the first journal for psychological research in 1881. If Freud is the “father of Psychiatry,” Wundt is likely the “Father of

Experimental Psychology.”

Wundt studies under Müller and Helmholtz prior to writing his first book,

Beiträge

zur Theorie der Sinneswahrnehmung (Contributions to the Theory of Sense

Perception)7 (1862). He follows this book with his second,

Vorlesungen über die Menschen -und Tierseele

(Lectures on

Human and Animal Psychology)8

(1863). Wundt has founded the first school of psychological thought by 1986 and

1897when he publishes Grundriss der

Psychologie (Outline

of Psychology) and Grundzüge der

physiologischen Psychologie (Principles of Physiological

Psychology).9 Ironically, Wundt’s success at training a new group experimental psychologists leads to a

distortion of his own views. One Wundt’s students, Edward Titchener (1867-1927), actively, but misleading, associates

Wundt’s view with Titchener’s own view, structuralism. Wundt names his view voluntarism,

and as we will see, it differs somewhat from the typical views attributed to

structuralism.

Wundt equates mentality with consciousness--to have

a mind requires that one has conscious experiences. Wundt holds that experimentation can help one to understand

simpler conscious phenomena, but not more complex phenomena. Essentially, Wundt limits psychology to studying

emotions and what contemporary cognitive scientists call sensation and perception.

For

Wundt, one must employ historical analysis and naturalistic (non-experimental)

observation to understand higher mental functioning such as reasoning, language

use, religious experience, etc..

As regards simpler conscious phenomena, Wundt distinguishes and studies two

kinds of sensation and emotion. Wundt studies perception--passive and involuntary combining multiple

sensations--and apperception--active voluntary

perception involving attention. He seeks

the fundamental constitutive elements of conscious mentality and the rules by

which these elements combine into more complex experiences. In this way, Wundt follows the mental

chemistry model of the mind that one finds in the British Empiricists. However, for Wundt attention and the will act

as a sort of catalyst making apperception active. Thus, Wundt differentiates himself from the

British Empiricists, in part, because of his introduction of an active,

volitional component to the mental chemistry account. In recognizing the role of attention in how people

perceive the world, Wundt anticipates the sorts of perceptual phenomena that

later psychologists (e.x. Gestalt Psychologists) come to recognize as crucial to

perception. In contrast, Wundt’s exclusion of higher mental

functioning from the domain of scientific studies of the mind differs from other

atomists.

Wundt breaks mental elements into two

categories; sensations and feelings. Sensations are the result of stimulation of the sense

organs. Each sensation has an intensity (ex. bright vs dim) and a modality (touch, taste, etc.).

Modalities have associated qualities such as

sweet and sour for taste. Feelings are distinct from sensations but co-occurring.

Wundt proposes a tridimensional account of feelings in which feelings have values along three

orthogonal dimensions; pleasantness-unpleasantness,

excitement-calm, and strain-relaxation.

|

|

|

Diagram

depicting Wundt’s theory of conscious experience. Wundt divides conscious experiences into

two kinds; passive perception and active apperception. Perception consists to two elements;

sensations and feelings. Apperception

consists of the elements of sensations and feelings together with

attention. Sensations have two

components (depicted on the right); intensity and modality. Each modality has qualities; in this case,

audition has tone and pitch. Feelings

(depicted on the left) vary along three orthogonal dimensions; pleasantness-unpleasantness,

excitement-calm, and strain-relaxation.

|

In order to study perception and apperception,

Wundt adopts two primary experimental techniques for studying these simple conscious phenomena; introspection

and reaction time. Reaction-time enters Wundt’s experimental repertoire

from Helmholtz and Donders. However, he eventually abandons the use of reaction time as too unreliable

for gathering data. For Wundt introspection provides immediate observation

of mental phenomena—direct observation unmediated by measuring and recording

devices. Unlike many other psychologists who follow him, Wundt uses introspection in a highly constrained fashion

in keeping with its use in physiology and psychophysiology. Wundt often

presents stimuli to experimental subjects, asking them to provide only yes or no answers

to signify whether they are experiencing a sensation. However, Wundt does

insist that subjects must be trained in

introspection to learn the appropriate categories.

Introspectionist Psychology:

Structuralism

Edward Titchener (1867-1927) is an English student of Wundt who comes to Cornell University where he continues

Wundt’s general project of trying to identify the elements of simple human consciousness and their interactions.

However, Titchener’s views and methods differ significantly from

Wundt’s. Unlike Wundt, Titchener seeks to apply the lens of experimental psychology to higher order mental phenomena

as well as simpler conscious phenomena. Titchener views experimental psychology as generating a morphological account of mental experiences—that

is, an account of the elements and composite structure of conscious mental experiences.

In his article, “

The Postulates of a Structural Psychology"10 (1898), Titchener tells readers that,

|

The primary aim of the experimental psychologist has been

to analyze the structure of mind; to ravel out the elemental processes from the tangle of consciousness, or (if we may change the metaphor) to isolate the

constituents in the given conscious formation. His task is a vivisection, but a vivisection which shall yield structural, not functional results. He tries to

discover, first of all, what is there and in what quantity, not what it is there for. (p.450) |

Likewise, Titchener differs from Wundt in that Titchener rejects the idea of an active volitional component of mental experiences.

Titchener rejects as unscientific volitional,

functional and teleological descriptions of mental processes at the psychological level.

Instead, Titchener follows the British Empiricists in supposing that psychology should create an account

of mental experiences in terms of structures created via the combination of basic elements through the mechanism of association.

Similarly, Titchener holds that mental

elements can only be known through their attributes. Titchener distinguishes three kinds of mental elements; sensations, images, and affections. Perceptions are composed of sensations, ideas are composed of images,

and emotions are composed of affections.

|

|

|

Diagram

depicting the Titchener’s structuralist account of conscious experiences.

Conscious experiences are composed of elements from three categories (in blue); perceptions, ideas, and

emotions. Each element has attributes (in green) that differentiates it and through which it is known. Perceptions and ideas have the attributes of quality, intensity, duration, clearness, and extensity.

Emotions have the attributes of quality, intensity, and duration.

|

Titchener’s use of introspection differs from Wundt’s in that it requires subjects to actively probe or analyze their

experiences to formulate reports. This requires extensive training. Titchener intends his training to cultivate an ability to observe and describe conscious

experiences without the tincture of “stimulus error.” Stimulus error occurs when subjects report their perceptions--reporting the meaning of the stimulus (or it’s conceptualization).

For instance, if a

subject saw an apple, the subject must report the hues, shapes, etc. of their

experience--they should not report seeing an apple or a fruit. This combination of indoctrination into

descriptive categories and active, even retroactive, analysis by subjects renders introspection even more methodologically problematic as an experimental

tool. In addition to the difficulties surrounding Titchener’s use of introspection, he also ignores as irrelevant numerous research areas where significant progress is

occurring. For instance, Titchener discounts animal behavior and evolution, abnormal behavior, learning, development, and inter-subjective variation.

Introspectionist

Psychology: Act Psychology

If you wish to find a

true introspectionist villain, Franz Clemens Honoratus Hermann Brentano (1838-1917) probably best fits that description. In his major work, Psychologie vom Empirischen Standpunkte11 or Psychology

from an Empirical Standpoint (1874), Brentano coins the term “intentionality” to characterize

his view that every mental act has an object to which it refers. For example, when someone sees an apple, they

see it as an apple, an object, and not merely as a qualitative experience.

Brentano tells readers:12

|

Every mental phenomenon is characterized by what the

Scholastics of the Middle Ages called the intentional (or mental) inexistence

of an object, and what we might call, though not wholly unambiguously,

reference to a content, direction towards an object (which is not to be

understood here as meaning a thing), or immanent objectivity. Every mental

phenomenon includes something as object within itself, although they do not all

do so in the same way. In presentation something is presented, in judgement

something is affirmed or denied, in love loved, in hate hated, in desire

desired and so on. This intentional in-existence is characteristic exclusively

of mental phenomena. No physical phenomenon exhibits anything like it. We

could, therefore, define mental phenomena by saying that they are those

phenomena which contain an object intentionally within themselves. (p.88-89) |

Brentano also eschews the study of static, simple

conscious experiences, framing mentality in terms of acts, that is, in terms of the mind being directed towards an object in order

to perform some function. Indeed, he holds that psychology should study mental processes in order to determine their

function.

Though Brentano never practices experimental psychology,

he does employ and advocate “phenomenological introspection,” in his theorizing about the nature of the mind and its processes.

In employing phenomenological introspection, the researcher either asks the

subject to analyze temporally extended processes such as inferences, or performs such an analysis themselves.

Though Brentano publishes very little, he influences many people, for instance, Freud.

The

Downfall of Introspectionist Psychology

It was the reliance upon introspection as their sole

experimental methodology, together with the implicit biases introduced by training subjects, and allowing

extended and retroactive introspective analysis that ultimately doomed

the methodological side of introspective psychology. Its practitioners make little to no effort to assess introspection’s calibration, or control for subject and experimenter

bias. Instead, perhaps naturally, they assume introspection is perfectly reliable across all of its methodological

uses. Quite to the contrary, introspection turns out to be relatively poorly calibrated and susceptible to massive subject and experimenter bias.

The behaviorists heavily criticize introspection as part of their rejection of the various forms of introspective psychology.

The contemporary uses of introspection, as a result, are highly

constrained and cross-validated. Indeed, Richard Nisbett and Timothy Wilson publish an influential literature

review in 1977,13 which still serves to highlight the perils of introspection.

As

we’ll see, the failure of introspection and the various schools of

psychological thought that rely heavily upon it also serves to shift the

emphasis from understanding the mind through conscious experience towards

understanding the mind through behavior and eventually cognition

Ebbinghaus: The Quantified Study of Memory as a Process

Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850-1909), begins one of the first systematic studies of memory in

1879. He studies only the ability to memorize nonsense syllables by rote.

He selects nonsense syllables since previous learning will not influence learning of these meaningless sounds.

This choice

represents one of his contributions to memory research, namely, that ease of memorization is increased by meaningfulness and relevance to the memorizer, and

vice versa. Ebbinghaus might have used some of his students as subjects, but he seems primarily to use only himself as a subject.

Ebbinghaus publishes his results in his book,

Über das Gedächtnis Untersuchungen zur Experimentellen Psychologie 14 or On Memory (1885), which is later translated and published as Memory:

A Contribution to Experimental Psychology15 (1913).

In On Memory Ebbinghaus reports results that are the basis for the “learning curve” and

the “forgetting curve.” The learning curve shows that learning time, measured as number of repetitions, increases exponentially

with the number of items memorized. Likewise, the increase in retention for each repetition decreases exponentially

so as to approach complete retention asymptotically. The forgetting curve is similarly exponential, showing the forgetting decreases at an exponential rate, so as to

approach complete failure of retention asymptotically. Specifically, R = e -t/s (where R = retention, t = elapsed time, and s = strength of original memory). Ebbinghaus

also documents the serial position effect, viz. the recency and primacy effects (subjects are more likely

to remember the last item in a series [recency] and the first item in a series [primacy]).

Likewise, Ebbinghaus documents “savings."

If one memorizes a list and then waits until recall is zero, one will still

generally relearn the list at a faster rate despite the seeming lack of recall.

Ebbinghaus terms the difference between the first and second memorization the savings.

Though Ebbinghaus is not prolific, does not identify himself with any psychological school of thought, and

does not seek out pupils, his work spurs research on memory. Ebbinghaus’ careful, well-designed experiments, his rigorous quantified results, statistical analysis, and

systematic presentation prove extremely influential.

|

|

|

|

Hermann Ebbinghaus

(1850-1909)

|

Typical

graph depicting data on savings.

|

|

(Left)

Table from Ebbinghaus presenting data on savings.

|

|

Functionalism

Most historians

consider William James (1842–1910) the first figure in the first school of

psychology in the United States--functionalism. Functionalism

overlaps significantly with both structuralism and behaviorism. James’ text, The Principles of Psychology16(1890),

actually predates by two years Titchner’s arrival a Cornell. Principles, a two volume, twelve hundred page text, makes James as famous and widely studied as Wundt.

Functionalism, much like pragmatism, the philosophical

movement with which James is also associated, has no central figure, nor a clear-cut doctrine.

However, functionalists make important criticisms and contributions to other schools of psychological thought, and do share several common

general commitments. (1) Functionalists oppose the search for the basic elements of thought that characterizes Wundt’s and Titchener’s views.

In fact, Principles portrays mentality as a stream of

consciousness incapable of analysis into elements. (2) Functionalists, in contrast to voluntarists and structuralists, think of the mind as dynamic, and mental processes as serving functions.

(3) They view the function of mind through the lens of evolution. Thus, functionalists understand mental processes and behavior in terms of the general goals of adaptation and selectional advantage.

(4) Unlike the rather rigid determinism of structuralism and behaviorism, functionalism tends to emphasize adaptation and differential responses driven by motivation.

(5)

Methodologically, functionalists tend to accept both introspection and behavioral observation as methodological

tools. Though few early functionalists conduct experiments, later

functionalists do conduct experiments. Functionalists also support psychological research on animals,

children, and abnormal populations as a means to understand normal human mentality.

(7) Finally, unlike Wundt, who views psychology’s mission as pure basic research, functionalists tend to see psychology as a means to improve society and people’s lives.

|

|

|

|

William

James (1842–1910)

|

John

Dewey (1859-1952)

|

The functionalists act as a counterweight to both

structuralism and behaviorism. For instance, historians often cite John Dewey’s “The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology"17 (1896) as the beginning of functionalism.

In this article Dewey criticizes the notion of the reflex arc as consisting of discrete

stages; stimulus and response. He also anticipates challenges facing behaviorists by noting the difficulties in specify a context-free notion of stimulus and response,

i.e., specifications capturing the

relevant features of particular stimuli and responses as well as spcifications

which predict the generalizations to future cases. Furthermore, the functionalist emphasis on practical applications in psychology, evolution, and diversity in methodology

and research areas help to plant the seeds for cognitive science.

Historians classify Edward Lee Thorndike (1874-1949) as a functionalist.

However, much of his work is arguably the

first research on conditioning and is certainly the first work on operant conditioning.

Thorndike publishes his dissertation, “Animal Intelligence: An Experimental Study of the Associative

Processes in Animals,” in 1898--predating Pavlov’s first public reference to conditioned reflexes by approximately a year.

Thorndike republishes this work in 1911 as

Animal Intelligence.18

|

|

|

|

Edward Lee Thorndike (1874-1949)

|

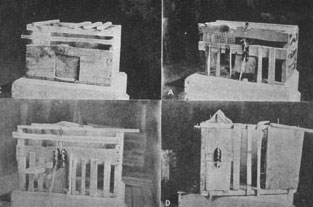

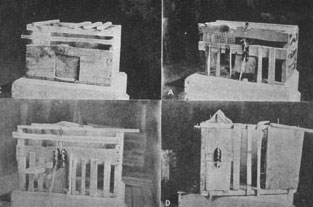

Four

of Thorndike’s puzzle boxes.

|

Thorndike studies a number of animals, but he is most famous for his studies of learning in cats using homemade puzzle boxes (above).

Thorndike puts a cat in a box, and lets it behave randomly until it

stumbles upon the release mechanism. He repeats this procedure until the cat can release itself in negligible time.

Thorndike then plots the decline

in time to escape relative to times in the box, using this ratio to characterize learning by “learning curves.” He formulates his generalized results in

terms of the law of effect.18

|

The Law of Effect is

that: Of several responses made to the same situation, those which are

accompanied or closely followed by satisfaction to the animal will, other

things being equal, be more firmly connected with the situation, so that, when

it recurs, they will be more likely to recur; those which are accompanied or

closely followed by discomfort to the animal will, other things being equal,

have their connections with that situation weakened, so that, when it recurs,

they will be less likely to occur. The greater the satisfaction or discomfort,

the greater the strengthening or weakening of the bond. (p.244) |

Behaviorism:

Pavlov’s Discovery of Classical Conditioning

Ironically, it is

Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936), a Russian physiologist studying digestion, who

provides the key finding around which Behaviorism evolves--classical conditioning.

|

|

|

|

Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936)

|

Depiction of Pavlov’s experimental apparatus for his

studies of digestion. From http://www.simplypsychology.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/classical-conditioning.html

|

Pavlov’s research includes the physiology and the

neurophysiology of temperament, conditioning, and involuntary reflex actions; but the bulk of his work focuses on digestion.

Pavlov’s experimental research on digestion was innovative and

sophisticated. Pavlov’s techniques include surgical removal of components of the digestive system from animals to

facilitate observations of their functions, lesioning nerve fibers to trace their function by observing the lesion’s effects, and implanting fistulas (tubes

or holes) draining into pouches to examine the organ's contents. In the 1890’s Pavlov’s lab is performing experiments on digestion using dogs.

Specifically, Pavlov’s group is studying the salivatory functions of

dogs by surgically externalizing a salivary gland so that the saliva could be collected and analyzed.

During their research Pavlov notices that the dogs begin to salivate before receiving

food. He calls this phenomena “psychic secretion”19 (p.7), and the lab begins to investigate this phenomena.

The researchers realize that these “psychic secretions” result from

associations between the food and other stimuli. These investigations eventually reveal what

Pavlov calls “conditioned reflexes,” and we now call classical conditioning.

|

|

A picture (left) of one of Pavlov’s dogs

complete with a fistula and collection chamber. From the Pavlov Museum in Russia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:One_of_Pavlov%27s_dogs.jpg

|

|

|

Animation

(left) depicting the elements and process of classical conditioning.

|

Pavlov first mentions his discovery in a lecture to the Society of Russian Doctors of St. Petersburg in 1899.

Printed accounts of the research appear in a

dissertation by Pavlov’s student, Wolfson, and in a report to the 1903 Congress of Natural

Sciences by Ivan Tolochinov,20 Pavlov’s collaborator. However, the discovery does not receive

significant attention until Pavlov discusses it in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1904. Pavlov’s own account

does not emerge until he publishes, Conditioned

reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex19 in 1927.

As illustrated in the diagram above, classical conditioning works by associating a stimulus that triggers a specific response

with a novel stimulus. Specifically, the unconditioned stimulus is a stimulus that elicits a particular

response called the unconditioned response. The conditioned stimulus is paired with the unconditioned stimulus

repeatedly so that the pairing elicits the unconditioned response. This repeated pairing increases the association between the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned response, as

reflected in the increasing likelihood of the conditioned stimulus eliciting the response in and of itself, making the unconditioned response

a conditioned response.

Pavlov also discovers and studies extinction and spontaneous recovery. When one elicits the conditioned response using only the conditioned

stimulus, the association between the conditioned stimulus and conditioned response weakness over time.

This weakening is

called extinction. After an association between a conditioned stimulus and a conditioned response reaches extinction, the conditioned stimulus can

elicit a conditioned response at a later; such

cases are called spontaneous recovery.

Behaviorism: John Watson

John Watson (1878-1958) adapts the work of Pavlov into a general approach to psychology,

which he presents in his 1913 paper, “ Psychology

as the Behaviorist Views It”.21 Watson embraces the idea of classical conditioning and sets the goal of psychological investigation as the prediction

and control of behavior. Additionally, Watson explicitly rejects the project of analyzing conscious experience, and the methodological tool of introspection.

Watson

describes his view as follows:21

|

Psychology as the behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is the

prediction and control of behavior. Introspection forms no essential part of its methods, nor is the scientific value of its data dependent upon the readiness with which they lend themselves to interpretation in terms of

consciousness. The behaviorist, in his efforts to get a unitary scheme of animal response, recognizes no dividing line between man and brute. The behavior of man, with all of its refinement and complexity, forms only a part

of the behaviorist's total scheme of investigation. (p.158) |

While Watson emphatically distances behaviorism from introspectionist psychologies, there are strong similarities under the surface.

Watson limits the appropriate phenomena of psychology to behavior, and sets the goals of

behaviorism as prediction and control of behavior. However, in practice Watson’s treatment of behavior is quite atomistic.

Watson divides behavior into four classes; explicit learned behavior such as

riding a bicycle, implicit learned behavior such as a rumbling stomach when smelling someone else’s dinner cooking, explicit unlearned behavior such as pulling your hand

away when it is hurt, and implicit unlearned behavior such as sweating when it is hot.

For the purposes of this class, we’ll focus upon Watson’s theoretical framework for the prediction and control of learned

behavior. Watson hypothesizes that explicit, complex learned behaviors--such as chess playing or language—can be understood as a series of simpler learned and unlearned behaviors

performed in a sequence cultivated by imitation and

classical conditioning. Simple learned behaviors are explained in terms of the environment, unlearned behaviors, and conditioning history.

For instance, implicit learned behaviors (like a fear response)

develop from simple conditioning and appropriate environmental ques. As Watson tells readers of his text, Behavior: An Introduction to Comparative

Psychology22(1914):

|

It is useless to ask young children to imitate acts as wholes where the elementary coördinates are lacking

or are ill-formed. There must be complete mastery of simple habits,--a readiness to respond to a difficult and complex environmental setting in a variety of ways—the ability to change

responses ever so slightly to meet the slightest change in a heretofore well-known object. In order to do this our stock in trade of acts must be much more numerous than the objects to which

we respond. … Apparently new coördinations are not established by imitation either in man or in animal. What is new is the combination or method of grouping. Where imitation appears there are found always groups of flexible

responses to every object worked with. (p.49) |

|

|

|

|

John Watson (1878-1958)

|

Diagram depicting how a more complex overt behavior, maintaining balance when riding a

bicycle, might be analyzed into simpler overt behaviors.

|

If this general approach seems familiar, it should. Watson, in effect, proposes an atomistism for behavior; a set of elemental behaviors—unlearned behaviors—from which all learned behaviors are

generated and combined through a process of association based upon contiguity and frequency.

Neo-Behaviorism

Historians classify the behaviorists

that follow Watson as neo-behaviorists. One can find the general motivation behind the neo-behaviorist research in the above quote from Watson.

On the one hand, Watson seeks to provide a highly mechanistic/deterministic account of

the generation of behavior. On the other hand, Watson wants to use his account to explain complex, flexible behavior, including behavior in novel circumstances.

Neo-behaviorists seek to expand the basic behaviorist framework to allow

for increased flexibility and complexity. For instance, suppose that a researcher trains a rat to associate food with a blue box. Sometimes when presented with the

blue box, the rat does not try to eat. Why doesn't the rat respond all the time?

Will the rat respond to the box when the researcher changes the color or the shape slightly?

How much change to the box can occur before the conditioned response is no longer triggered?

Neo-behaviorists continue to view overt behavior as the central phenomena for psychology.

They also hold that the prediction and control of behavior is the central goal of psychology.

Learning reamins central to psychology. Finally, neo-behaviorists share Watson’s conviction that animal models of learning and perception are easily and robustly transferable to humans.

Neo-behaviorists commonalities go beyond Watson as well.

For example, neo-behaviorists share Watson’s general commitment to grounding psychology in

observation. However, unlike Watson, neo-behaviorists seek to tie all theoretical terms to experimental operations for the measurement and/or application of those terms.

Researchers call this view about the treatment of unobservable theoretical terms operationalism.

Operationalists refer to the specification of a set of operations for a theoretical term as an

operational definition. Watson and the neo-behaviorists see animal experimentation as essential to psychological research because of the continuity of animal learning and perception with human learning and perception.

However, neo-behaviorists see additional value in animal experimentation because it allows for more rigorous controlled experiments.

Lastly, neo-behaviorists differ from

Watson and one another in the manner in which they seek to extend behaviorism.

Radical behaviorists like B.F. Skinner hold that the prediction and control of behavior must eschew

internal, unobservable mental and physiological events. Methodological behaviorists allow for appeal to internal states so long as those terms are tied to observation.

Neo-Behaviorism: Radical Behaviorism

Historians classify Burrhus Frederic “Fred” Skinner (1904-1990) as a neo-behaviorist, though

Skinner is very strongly associated with behaviorism in the popular mind. Skinner’s association with behaviorism is due in part to his theoretical approach.

Like Watson, Skinner insists that theorists focus on predicting and

controlling behavior. Likewise, Skinner also supposes that conscious mental states have no part to play in psychological theorizing, insisting instead that environment and conditioning

history provide sole basis for the psychological understanding of human conduct.

However, Skinner’s theoretical perspective diverges from Watson on several key points.

Skinner adopts an approach called “functional

analysis”

that he traces to Ernst Mach. Functional analysis has a quite different

meaning for Skinner than for the theorists we will discuss later. For Skinner functional analysis characterizes dependencies--not meticulously detailed

step-wise causal relationships--between observable phenomena, i.e., between conditioning histories and

environments. Specifically, Skinner understands functional analysis as a

method for establishing relationships between stimuli and responses through the

application of operant conditioning. Skinner's analysis is often called a

"three-term contingency" analysis in that it characterizes the

environmental features that act as a trigger for the behavior (sometimes called

the discriminative stimulus), the response (the specific rigorously characterized

behavior), and reinforcement (the consequence of the behavior that positively or

negatively influences the probability of the behavior in the eliciting

conditions). While Watson rejects Thorndike’s law of effect as too subjective, Skinner creates a systematic, objective formulation of the learning paradigm--operant

conditioning. Unlike Watson, Skinner does not understand behavior as something elicited by environmental stimuli.

Rather, Skinner views behavior as active operations on the environment. Likewise, Skinner sees

patterns of behavior emerging as a result of those behaviors being selected by contingent environmental reinforcement.

Skinner writes his famous book, The Behavior of

Organisms23 (1938), while at his first job at the University of Minnesota.

In that book Skinner reformulates Thorndike’s

law of effect so that it describes environmental selection of behavior through the reinforcement resulting from the behavior. Skinner makes no reference to subjective states like desires, drives,

etc. in characterizing reinforcement.

In operant conditioning a creature’s behavior--often

random behavior--is either positively or negatively reinforced

(rewarded or punished). The probability of the behavior occurring again in the relevant eliciting conditions increases

or decreases in proportion to the number of behavior/reinforcement pairings. For example, as depicted in the animation above, a cage might be divided into two

sections. Whenever a rat wanders into one section, experimenters administer an electric shock. Over time, the probability that the rat will,

for instance, leave the section of the cage where it recieves shocks whenever placed there increases.

Operant conditioning together with classical conditioning broaden the range of learned

organism-environment interactions. Classical conditioning provides a mechanism whereby stimuli from the

environment can elicit a response, i.e., stimuli cause organism responses. Operant conditioning provides a mechanism

whereby behavior becomes part of the organism’s repertoire as a function of its consequences, i.e., consequences elicit behaviors.

Part of the lore of cognitive science and behaviorism involves Skinner. In 1957 Skinner publishes a book, Verbal

Behavior,24 based upon lectures originally given at the University of Minnesota, and further refined at Columbia and as the lectures William James. Skinner supposes that verbal behavior has no significant and essential

differences from other sorts of behavior. For instance, he denies that verbal behavior results from an innate capacity. Skinner proposes to treat verbal behavior using his functional analysis method.

In 1959 Noam Chomsky publishes a

review of Skinner’s book.25 Often accounts of the development of cognitive science portray Chomsky’s review as a

refutation of behaviorism and the beginning of cognitive science. Chomsky’s review represents an informed, articulate, and forward-looking indictment of the promise of Skinner’s functional analysis as

a methodology for investigating language. Few authors could hope improve upon Chomsky’s articulate formulation of the task

facing anyone who seeks to understand language and language acquisition:25

|

We constantly read and hear new sequences of words, recognize them as sentences,

and understand them. It is easy to show that the new events that we accept and understand as sentences are not related to those with which we are familiar by

any simple notion of formal (or semantic or statistical) similarity or identity of grammatical frame. Talk of generalization in this case is entirely pointless and empty. It appears that we recognize a new item as a sentence not because it

matches some familiar item in any simple way, but because it is generated by the grammar that each individual has somehow and in some form internalized.

The child who learns a language has in some sense constructed the grammar for

himself on the basis of his observation of sentences and nonsentences (i.e., corrections by the verbal community). Study of the actual observed ability of a speaker to distinguish sentences from nonsentences, detect ambiguities, etc.,

apparently forces us to the conclusion that this grammar is of an extremely complex and abstract character, and that the young child has succeeded in carrying out what from the formal point of view, at least, seems to be a

remarkable type of theory construction. Furthermore, this task is accomplished in an astonishingly short time, to a large extent independently of intelligence, and in a comparable way by all children. Any theory of learning must cope with

these facts. (pp. 56-57)

|

Similarly, Chomsky’s authoritative and tightly argued paper compels the reader’s assent

to his evaluation25

|

Anyone who seriously approaches the study of linguistic behavior, whether

linguist, psychologist, or philosopher, must quickly become aware of the enormous difficulty of stating a problem which will define the area of his investigations, and which will not be either completely trivial or

hopelessly beyond the range of present-day understanding and technique. In selecting functional analysis as his problem, Skinner has set himself a task of

the latter type. (p.55) |

However, as we shall see, Chomsky’s insightful analysis reflects thinking among many theorists of the time—including behaviorists--with regard to many areas of research.

Indeed, other neo-behaviorists seek to further extend the scope of behaviorism, not by finding new learning mechanisms, but by opening the black box in which Skinner’s functional analysis places the mind.

Neo-Behaviorism:

Hull’s Methodological Behaviorism

Clark Leonard Hull (1884-1952) represents a bridge between behaviorism and cognitive

psychology. Specifically, Hull and Tolman (next) come to view behavior as goal- oriented, and introduce “intervening variables” between stimulus and response

in order to explain behavior. For Hull, unlike Tolman, experimenters must characterize intervening variables as primarily physiological. Hull articulates his vision for psychological theories in an early paper:26

|

…sound scientific theory has usually led not only to

prediction but to control; abstract principles in the long run have led to concrete

application. With powerful deductive instruments at our disposal we should be

able to predict the outcome of learning not only under untried laboratory

conditions, but under as yet untried conditions of practical education. We

should be able not only to predict what rats will do in a maze under as yet

untried circumstances, but what a man will do under the complex conditions of

everyday life. In short, the attainment of a genuinely scientific theory of

mammalian behavior offers the promise of development in the understanding and

control of human conduct in its immensely varied aspects which will be

comparable to the control already achieved over inanimate nature, and of which

the modern world is in such dire need. (p.516)

|

|

|

|

Clark

Leonard Hull (1884-1952)

|

In his Principles of Behavior27 (1943) Hull introduces a mathematical formulation to

capture the relationship between environmental situations, intervening variables, and learned responses. The

elements of this equation are as follows: Drive, D, (fueled by biological need), Habit Strength, SHR, (the

connection between environmental situation and response measured as the number

of pairings), and Reaction Potential, SER,

(the probability of the subject manifesting a learned response). These yield the equation: SER

= SHR x D.

Hull operationally defines habit strength as the number

of pairings between environmental situation and the response. Drive is operationally defined in terms of the length of deprivation. Hull

continues to introduce additional operationally defined variables to his basic framework throughout his career.

Neo-Behaviorism:

Purposive Behaviorism

Like Hull, Edward Chace Tolman (1886-1959), espouses the use of intervening

variables in the explanation of behavior. However, Tolman differs from Hull in that Tolman supposes animals have

internal states characterizable in terms of their purpose, for instance, expectations and representations.

In his article, “A

New Formula for Behaviorism,”28 (1922) Tolman

explains his perspective to readers:

|

The two essential theses which we wish to maintain in

this paper are, first, that such a true non-physiological behaviorism is really

possible; and, second, that when it is worked out this new behaviorism will be

found capable of covering not merely the results of mental tests, objective

measurements of memory, and animal psychology as such, but also all that was

valid in the results of the older introspective psychology. And this new

formula for behaviorism which we would propose is intended as a formula for all

of psychology--a formula to bring formal peace, not merely to the animal

worker, but also to the addict of imagery and feeling tone. (pp.46-47) |

In several of his works Tolman develops and defends three

important concepts; expectation, cognitive maps, and latent

learning. In his 1932 book, Purposive Behavior in Animals and Men,29 Tolman further

refines his view, arguing against Watson that behavior should not be understood in terms of individual conditioned reflexes and their ordered chains. Rather, Tolman suggests that researchers need

to understand behaviors as goal-directed acts in which component elements are organized to accomplish a purpose.

In Purposive Behavior

and in an earlier paper, "Introduction and Removal of Reward, and Maze

Performance in Rats,"30 Tolman also argues that learning can

occur without reward or

punishment. Specifically, Tolman demonstrates that rats learn the location of food in a maze, and later utilize that knowledge, as a result of wandering around within the maze when they are not

hungry. A phenomenon he calls latent learning (p.344).29,30

In the first of an influential series of papers published

in the Journal of Experimental Psychology31-35 (1946-1949) Tolman and colleagues argue

that rats learn to negotiate radial mazes in virtue of their developing expectancies. Which they define as:31

|

When we assert that a rat expects food at location L,what

we assert is that if (1) he is deprived of food, (2) he has been trained on path P, (3) he is now put on path P, (4) path P is now

blocked, and (5) there are other paths which lead away from path P, one of which points directly to location L, then he will run down the path

which points directly to location L.

When we assert that he does not expect food at location L,what we assert is that, under the same conditions, he will not

run down the path which points directly to location L. (p.430)

|

In “Cognitive

Maps in Rats and Men36 (1948) Tolman introduces the idea of a cognitive map:

|

Rather, the incoming impulses are usually worked over and elaborated in the central control room into a tentative, cognitive-like map of

the environment. And it is this tentative map, indicating routes and paths and environmental relationships, which finally determines what responses, if any, the animal will finally

release. (p.192)

|

|

|

|

|

Edward

Tolman (1886-1959)

|

Animation showing 1 the original training maze, 2 the testing maze with the arm

blocked, and 3 an overlay of both mazes showing how the choice of arm 6 by rats illustrates their knowledge of the relative position of the room where

the food is located.

|

Gestalt Psychology

Historians generally locate the start of Gestalt psychology to the 1912 publication of “Experimentelle

Studien über das Sehen von Bewegung” or “Experimental Studies on the Perception of Motion”37 by Max Wertheimer (1880-1943). Wertheimer conducted this research with his two research assistants, Kurt Koffka and

Wolfgang Köhler. The emphasis of their work is the study of perception, particularly the rules by which perceptual

inputs are organized into meaningful wholes. Wertheimer articulates the central doctrines and insights of Gestalt psychology

in his classic paper, “Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt” or “Laws

of Organization in Perceptual Forms”38 (1923). Gestalt

psychology contributes to the development of cognitive science in two

ways. First, Gestalt psychology marks a shift in the study of perception away from pure physiology and psychophysiology

towards the cognitive. Second, Gestalt psychologists argue that behavior

is driven as much by insight and problem solving as by classical and operant

conditioning. The influence of gestalt psychologists manifests itself less through a theory than through an ever increasing body of perceptual phenomena that resist explanation by either

introspective techniques or by the reflexive techniques of behaviorists. For instance, Wertheimer articulates several

basic principles by which perceptual forms seem to be organized in Laws of Organization, such as the factor of closure (below), but he does not offer an overarching

framework for understanding vision.

|

|

|

|

|

Max Wertheimer (1880-1943)

|

Animated

gif illustrating the phi phenomenon explored in “Experimental

Studies on the Perception of Motion.” In the phi phenomena properly sequenced lights give rise to the

perception of motion.

|

Examples

illustrating the law of closure in which objects grouped together in

perception are seen as a whole.

|

Wolfgang Köhler (1887-1967) contributes greatly to the development of Gestalt psychology. However, it is through his book, The

Mentality of Apes39 (1917), that he makes his greatest contribution to the

development of cognitive science. In his

book Köhler describes the behaviors of various chimpanzees at the Prussian Academy of

Sciences anthropoid research station. He

argues that these animals seem to learn by insight and problem solving more

than by Thorndike’s trial and error. Among the researchers Köhler

influences is a young Tolman, whose two review papers called "Habit

Formation and Higher Mental Processes in Animals"40,41 (1927,1928)

incorporate the idea of insightful

learning, and analyze results of researchers who replicate and extend Köhler’s

experiments.

|

|

|

|

Wolfgang Köhler (1887-1967)

|

Pictures

taken from The Mentality of Apes showing chimpanzees using various

techniques like stacking boxes to reach suspended fruit.

|

The Mathematical Analysis of Communication and Control

As we will see in the

chapters on the development of the formal treatment of computing and the development of computers, mathematical and techinical developments greatly

facilitate the emergence of an information processing account of cognition.

For now, we will consider four figures central to the development of information theory and cybernetics.

The work of these theorists plays a central role in early information processes accounts because the researchers intended their research to have wide applicability, including both artifical biological

systems.

Norbert Wiener (1894-1964), a mathematician, represents an important influence as well

as a general trend; after WWII research on human performance of skill-based tasks increases dramatically.

These tasks lend themselves to characterization as information processing tasks.

Wiener’s 1943 article, "Behavior,

Purpose and Teleology"42 and his 1948 book, Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine43

represent one important and influential first step in this direction.

In Cybernetics and "Behavior" Wiener introduces such

terms as “input” and “output” in outlining his interdisciplinary approach to the study of complex, goal-oriented systems.

Cybernetics views such systems as

complex systems interacting continuously with the environment through such mechanisms as communication, control, feedback, and self-organization.

Historians often cite the publication of "Behavior, Purpose and Teleology" together with the publication of

“A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity”44 by Warren Sturgis McCulloch (1898-1969) and Walter Pitts (1923-1969) as the beginning of the Cybernetics

movement in the 20th century.

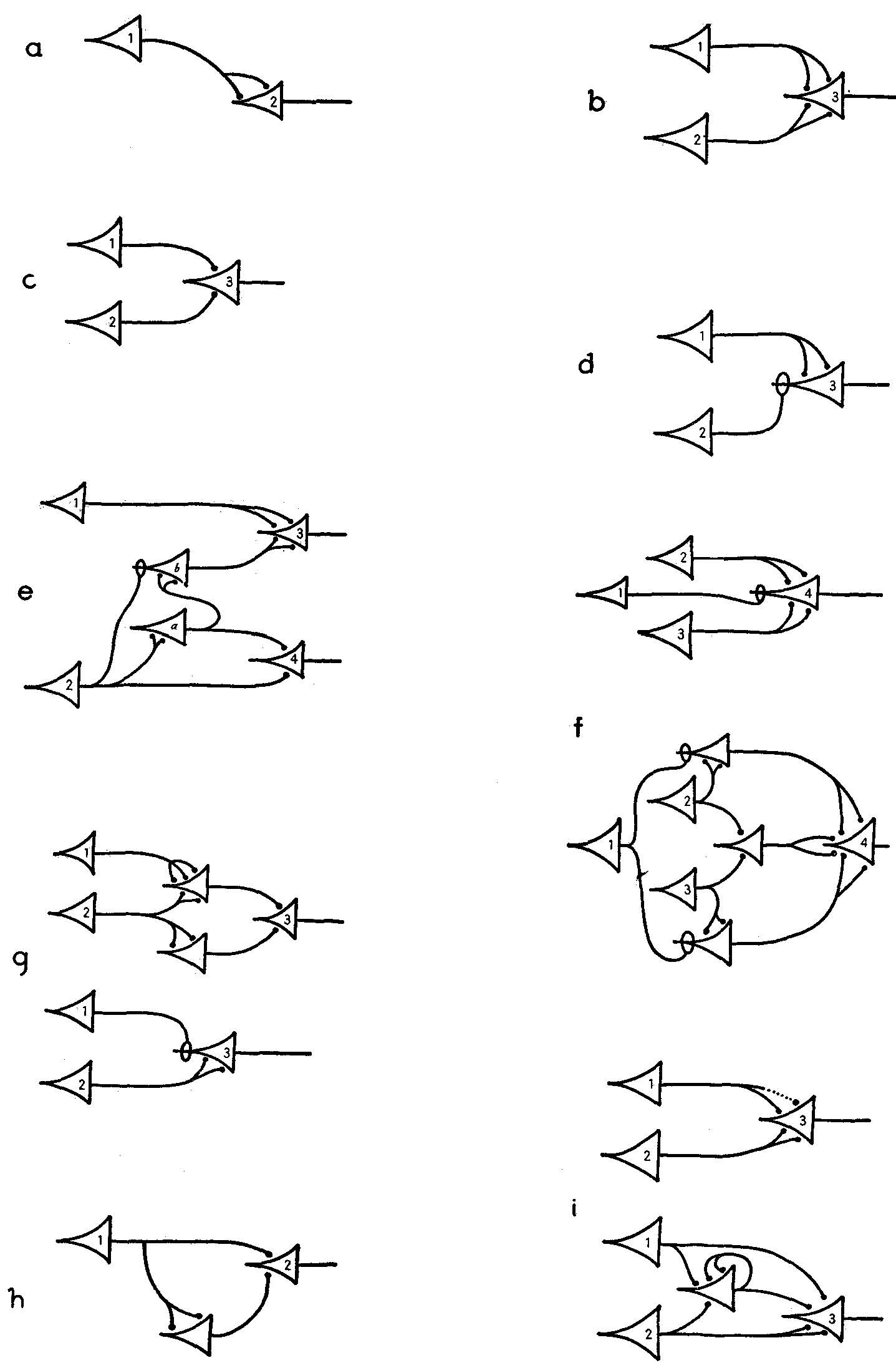

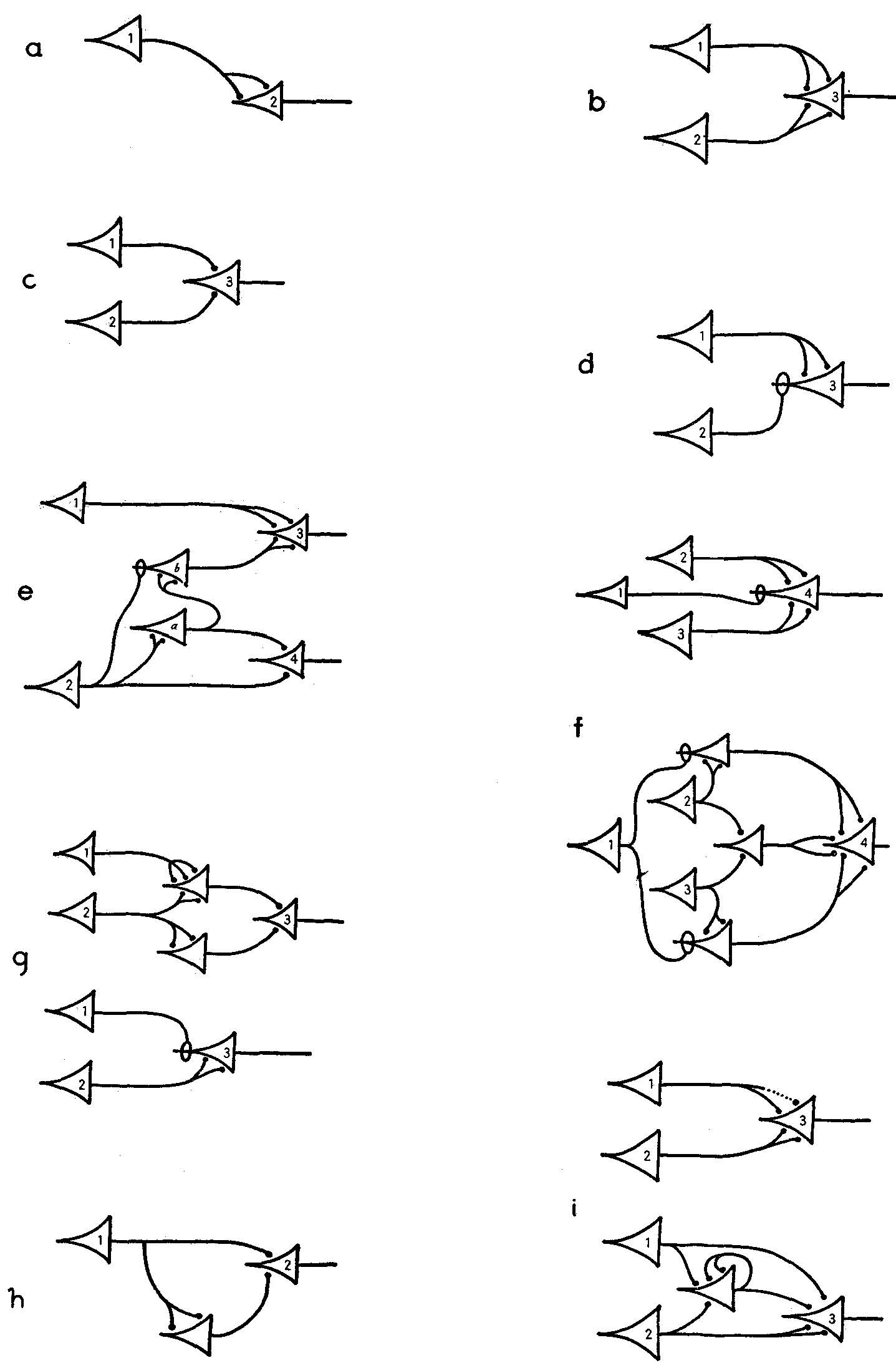

In their paper McCulloch and Pitts show how, by interpreting neuronal

activity as on-off (or binary), one can show how44

|

The "all-or-none" law of nervous activity is sufficient to insure that the activity of any neuron may be

represented as a proposition. Physiological relations existing among nervous activities correspond, of course, to relations among the propositions; and the

utility of the representation depends upon the identity of these relations with those of the logic of propositions. To each reaction of any neuron there is a

corresponding assertion of a simple proposition. This, in turn, implies either some other simple proposition or the disjunction or the conjunction, with or

without negation, of similar propositions, according to the configuration of the synapses upon and the threshold of the neuron in question. (p.117) |

From these results,

McCulloch and Pitts conclude:44 "Thus, in psychology, introspective, behavioristic, or physiological the fundamental

relations are those of two-valued logic." (p.131) In addition, McCulloch and Pitts show how logical functions could be computed by circuits created from

neurons (see below).

|

|

|

|

|

Norbert Wiener (1894-1964)

|

Warren McCulloch

(1898-1969)

|

|

|

|

|

Walter Pitts

(1923-1969)

|

Claude Shannon (1916-2001)

|

Diagram of neuronal circuits from McCulloch

and Pitts

|

Claude Shannon

(1916-2001), yet another mathematician, lays the foundations of information theory in his 1948 paper, "A Mathematical Theory

of Communication."45

The theory is specifically intended to address the problem of

transmitting information over a noisy channel.

However, it influences theories of perception and mental representation

as well as adding to the general conception of information processing as a

central feature of mentality.

These

four men have an additional connection in that they were all at MIT in 1956,

when one of the significant conferences in the development of cognitive science

occurs—The Second Symposium on Information Theory. While there are a number of important

conferences during this period in both the United States and Britain, many

historians point to the MIT conference in particular.

Information

Processing Psychology

Donald Eric Broadbent (1926-1993), an English

experimental psychologist publishes his book, Perception and Communication,46 in 1958.

It outlines theories of selective attention

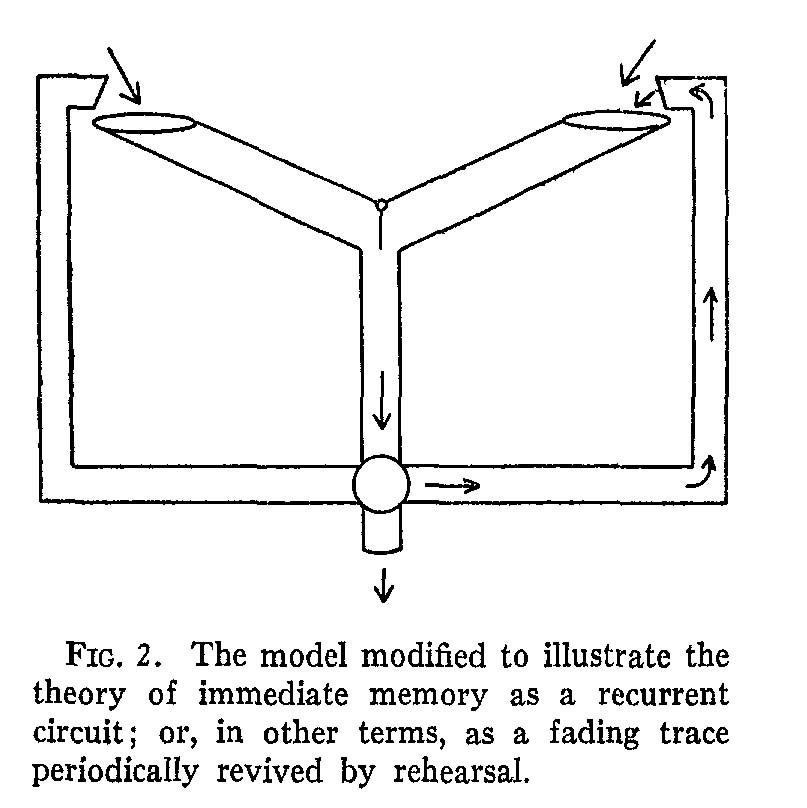

and short-term memory using computer analogies. Among the contributions in Broadbent’s book is his filter theory of attention and memory.

On Broadbent’s

theory, the brain holds simultaneously presented sensory input in a short-term sensory memory acting like a recurrent circuit.

These inputs can be retained through rehearsal, but will disappear once

allowed to degrade. Input in the sensory memory can pass through a filter selecting for specific physical signal

characteristics at which point the input enters a limited capacity channel for additional processing.

Once analyzed for

meaning, it enters conscious awareness. Broadbent's model proves important

in two respects: First, it suggests that the brain actively selects among

information. Second, it suggests that the brain has real limitations in

the amount of information it can process.

George Armitage Miller (1920- ), presents a paper at the 1956 MIT conference,

"The Magical Number

Seven, Plus or Minus Two,"48 which he publishes later

that year. The paper outlines experimental work by Miller

and others showing that short-term memory (STM) has a capacity of seven items plus or minus two items.

Miller also

determines that chunking--linking individual items together--allows more complex items to be stored as single items, and improves recall.

Miller’s paper is framed within information

theory. In the paper’s summary, Miller tells readers that48

|

...the span of absolute judgment and the span of

immediate memory impose severe limitations on the amount of information that we are able to receive, process, and remember. By organizing the stimulus input

simultaneously into several dimensions and successively into a sequence or chunks, we manage to break (or at least stretch) this informational bottleneck.

(p.95) |

Miller goes on to co-found

the Center for Cognitive Studies at Harvard and publishes an important book, Plans and the Structure of Behavior,49 in 1960. Plans

explores the potential of cybernetics in psychology through formulating many basic psychological process in terms of plans. They begin their first chapter by telling readers:49

|

The authors of this book believe that

the plans you make are interesting and that they probably have some relation to

how you actually spend your time during the day. You imagine what your day is

going to be and you make plans to cope with it. A Plan is any hierarchical

process in the organism that can control the order in which a sequence of operations

is to be performed. The image is all the accumulated, organized knowledge that

the organism has about itself and its world. This chapter considers what modern

psychology has to say about images and plans. (p.5) |

Development as Inherently Cognitive

Jean Piaget (1896-1980), a Swiss scientist studies

intellectual development in children as early as 1927. His research into development as well as his invention of experimental paradigms and demonstrations resist both

introspective and behavioral explanation. Piaget suggests that the human intellect develops through a series of stages.

According to Piaget’s theory,

humans progress through a series of developmental stages. Each stage represents a movement towards more

abstract symbolic forms of reasoning, and is characterized by a particular schema or structure through which the person interacts with, and understands,

the world.

Piaget considers himself an epistemologist, and writes an

number of works in epistemology. His orientation in investigating development through schemas for understanding the world represents a European tradition

with its origins in Kant. Similar research in other areas of development, for instance, in language acquisition, likewise challenges

introspective and behaviorist perspectives both in terms of the breadth and robustness of development as well as regular timeframes in which development

seems to occur.

|

|

|

|

Jean Piaget (1896-1980)

|

Ulric Neisser (1928- )

|

The

Final Step

Ulric Neisser (1928- ), a student of Miller, helps to catalyze and popularize cognitive

psychology when his book, Cognitive Psychology,50 is published in 1967.

In that book, Neisser tells

readers that48 “Cognitive Psychology refers to all processes by which the sensory input is transformed, reduced elaborated, stored, recovered, and used.” (p.4)

Neisser attempts to integrate work from areas

like perception, thinking, concept formation, and linguistics within a general information-processing framework.

For

instance, Niesser characterizes the research project of the cognitive psychologists by telling readers that50

|

The task of a psychologist in trying to understand human

cognition is analogous to that of a man trying to discover how a computer has

been programmed. In particular, if the program seems to store and re-use information, he would like to know by what

"routines" or "procedures" this is done. Given this purpose, he will not care much whether his particular computer stores

information in magnetic cores or in thin films; he wants to understand the program, not the "hardware". By the same token, it would not help the

psychologist to know that memory is carried by RNA as opposed to some other medium. He wants to understand its utilization, not its incarnation. (p.6) |

Three years after

Neisser publishes Cognitive Psychology the journal Cognitive

Psychology comes into being in 1970. Needless to say, single

events like Neisser's book or the founding of a journal do not mark a sudden

transformation in psychology. Rather, such events are merely indicative of

widespread and temporally extended changes within psychology. Likewise,

the cognitive psychology envisioned by Niesser in the above quote differs from

the cognitive psychology and cognitive science we find today. For example,

the idea that one can ignore the "hardware" in understanding the

software has proven incorrect.

Summary

As we have seen, the development of cognitive psychology

requires several factors to come together; the development of experimental methodologies, the refinement of animal and other models,

increases in the knowledge of human mentality, development, and physiology, and the development of technical ideas such as information and computation. The coalescing of these factors allows for

the conceptual framing of cognitive phenomena as well as its systematic experimental investigation.

Bibliography

| 1. |

Bessel, F.W. Astronomische

Beobachtungen auf der Königlichen Universitäts-Sternwarte in Königsberg von

(Königsberg, 1823). |

| 2. |

Pond, J.

Astronomical Observations Made at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich in the

Year 1832, Part 5: Supplement (London, 1833). |

| 3. |

von Hemholtz,

H.L.F. Fortpflanzungsgeschwindigkeit der Nervenreizung (On the Rate of

Transmission of the Nerve Impulse). Bericht

fiber die Bekanntmachung geeigneten Verhandlungen der KSniglichen Preussischen

Akademie der W issenschaften zu Berlin 4,

14-15 (1850). |

| 4. |

Nicolas, S. On the

Speed of Different Senses and Nerve Transmission. Psychological Research 59,

261-268 (1997). |

| 5. |

De Jaager, J.J. De

Physiologische Tijd bij Psychische Processen: Academisch Proefschrift (de

Hoogeschool te Utrecht). (van de Weijer, Utrecht, 1865). |

| 6. |

Donders, F.C. Die

Schnelligkeit Psychischer Processe. Archiv

fúr Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medizin 6, 657-681 (1868). |

| 7. |

Wundt, W.M.

Beiträge zur Theorie der Sinneswahrnehmung (Contributions to the Theory of

Sense Perception) (Winter, Leipzig, 1862). |

| 8. |

Wundt, W.M.

Vorlesungen über die Menschen- und Thier-Seele (Lectures on Human and Animal

Psychology) (Voss, Leipzig, 1863). |

| 9. |

Wundt, W.M.

Grundzüge der Physiologischen Psychologie (Principles of Physiological

Psychology) (Engelmann, Leipzig, 1873-4). |

| 10. |

Titchener, E. The

Postulates of a Structural Psychology. Philosophical

Review 7, 449-465. (1898). |

| 11. |

Brentano, F.

Psychologie vom Empirischen Standpunkte (Psychology from an Empirical

Standpoint) (Verlag Ven Dunker & Humblot, Leipzig, 1874). |

| 12. |

Brentano, F.

Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (Routledge, New York, NY, 1995). |

| 13. |

Nisbett, R.E. &

Wilson, T.D. Telling More Than We Can Know: Verbal Reports on Mental Processes.

Psychological Review 84 231-259

(1977). |

| 14. |

Ebbinghaus, H. Über

das Gedächtnis (Verlag Von Dunker & Humblot, Leipzig, 1885). |

| 15. |

Ebbinghaus, H.

Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology (Columbia University Teachers

College, New York, 1913). |

| 16. |

James, W. The

Principles of Psychology (Henry Holt & Co., New York, NY, 1890). |

| 17. |

Dewey, J. The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology. Psychological Review 3, 357-370 (1896). |

| 18. |

Thorndike, E.L.

Animal Intelligence (The Macmillan Company, New York, NY, 1911). |

| 19. |

Pavlov, I.

Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the

Cerebral Cortex (Oxford University Press, London, 1927). |

| 20. |

Tolochinov, I.F.

Contributions à l'étude de la Physiologie et de la, Psychologie des Glandes

Salivaires. Congress of Natural Sciences

in Helsingfors Proceedings (1903). |

| 21. |

Watson, J. Psychology

as the Behaviorist Views It. Psychological

Review 20, 158-177 (1913). |

| 22. |

Watson, J.B.

Behavior: An Introduction to Comparative Psychology (Henry Holt and Company, New

York, NY, 1914). |

| 23. |

Skinner, B.F. The Behavior of Organisms (Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York, NY 1938). |

| 24. |

Skinner, B.F. Verbal Behavior (Appleton-Century-Crofts, East Norwalk, CT, 1957). |

| 25. |

Chomsky, N. A Review of Skinner's Verbal Behavior. Language 35, 26-58 (1959). |

| 26. |

Hull, C.L. The Conflicting Psychologies of Learning--A Way Out. Psychological Review 42,

491-516 (1935). |

| 27. |

Hull, C.L. Principles of Behavior, an Introduction to Behavior Therapy (D. Appleton-Century, New York, NY, 1943). |

| 28. |

Tolman, E.C. A New Formula for Behaviorism. Psychological Review 29, 44-53 (1922). |

| 29. |

Tolman, E.C. Purposive Behavior in Animals and Men (Century, New York, NY, 1932). |

| 30. |

Tolman, E.C. & Honzik, C.H. Introduction and Removal of Reward, and Maze Performance

in Rats. University of California Publications in Psychology 4, 257-275 (1930). |

| 31. |

Tolman, E.C. Studies in Spatial Learning. I. Orientation and the Short-Cut. Journal of Experimental Psychology

36, 13-24 (1946). |

| 32. |

Tolman, E.C. & Gleitman, H. Studies in spatial learning: VII. Place and response learning under different degrees of motivation.

Journal of Experimental Psychology 39, 653-659 (1949). |

| 33. |

Tolman, E.C., Ritchie, B.F. & Kalish, D. Studies in spatial learning. II. Place learning versus response learning.

Journal of Experimental Psychology 36, 221-229 (1946). |

| 34. |

Tolman, E.C., Ritchie, B.F. & Kalish, D. Studies in spatial learning. IV. The transfer of place learning to other starting paths.

Journal of Experimental Psychology 37, 39-47 (1947). |

| 35. |

Tolman, E.C., Ritchie, B.F. & Kalish, D. Studies in spatial learning. V. Response learning

vs. place learning by the non-correction method. Journal of Experimental Psychology 37, 285-292 (1947). |

| 36. |

Tolman, E.C. Cognitive Maps in Rats and Men. Psychological Review

55, 189-208 (1948). |

| 37. |

Wertheimer, M. Experimentelle Studien über das Sehen von Bewegung (Experimental Studies on the Perception of Motion).

Zeitschrift Für Psychologie 61, 161-265 (1912 ). |

| 38. |

Wertheimer, M. Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt (Laws of Organization in Perceptual Forms).

Psycologische Forschung 4, 301-350 (1923). |

| 39. |

Köhler, W. The Mentality of Apes (Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., London, 1926). |

| 40. |

Tolman, E.C. Habit Formation and Higher Mental Processes in Animals.

The Psychological Bulletin

24, 1-35 (1927). |

| 41. |

Tolman, E.C. Habit Formation and Higher Mental Processes in Animals.

ThePsychological Bulletin

25, 24-53 (1928). |

| 42. |

Rosenblueth, A., Wiener, N. & Bigelow, J. Behavior, Purpose and Teleology". Philosophy of Science

10, 18-24 (1943). |

| 43. |

Wiener, N. Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (MIT University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1948). |

| 44. |

McCulloch, W.S. & Pitts, W. A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics

5, 115-133 (1943). |

| 45. |

Shannon, C. A. Mathematical Theory of Communication. The Bell System Technical Journal

27, 379-423 623-656 (1948). |

| 46. |

Broadbent, D.E. Perception and Communication (Pergamon Press, Elmsford, NY US, 1958). |

| 47. |

Broadbent, D.E. A Mechanical Model for Human Attention and Immediate Memory. Psychological Review

64, 205-215 (1957). |

| 48. |

Miller, G.A. The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two. Psychological Review

63, 81-97 (1956). |

| 49. |

Miller, G.A., Galanter, E. & Pribram, K.H. Plans and the Structure of Behavior (Henry Holt and Co, New York, NY US, 1960). |

| 50. |

Neisser, U. Cognitive Psychology (Appleton-Century-Crofts, East Norwalk, CT US, 1967). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|