Since about 1960, though, the New Deal coalitions have been unraveling in the face of complex

social change. The United States has entered upon a new sociopolitical setting most aptly

described as "postindustrial"involving such conditions as a dramatic increase in national wealth,

advanced technological development, the central importance of knowledge, the elaboration of

national electronic communications processes, new occupational structures, and with them new

life-styles and expectations, which is to say, new social classes and new centers of power.

The social and political world with which the parties must deal has changed so markedly from

what it was in the age of Franklin Roosevelt that the party system could not help but be altered.

A different mix of policy issues has been thrust upon the political agenda. Lines of social

conflict have shifted. New interest groups have appeared and old groups have found themselves

with new interests. And as the Democratic and Republican parties have grappled with this

changing en-vironment, they have acted in ways which, inevitably, have increased the impact of

the broad external social changes on the composition of their respective coalitions.

Today the party alliances and voting patterns which gave a distinctive stamp to the New Deal era

have vanished. Some features of the past, of course, are always embedded in the present. We

insist that the New Deal coalitions have left the scene, not because nothing of them remains, but

because the alliances, issues, and cleavages which distinguished them are no longer those which

demarcate the Democratic and Republican coalitions.

The argument of this chapter with regard to the shifting partisan alliances invokes a common

observation about social change. At some point, the differences from earlier periods cannot

properly be described simply as "more." The quantitative progression produces qualitative

change. The analogy of a small snowball at the top of an inclination gradual at the start and

becoming ever steeper is not inappropriate. The ball of snow begins to roll, slowly at first--and

with its small mass, it grows but slowly; but as the mass enlarges and the inclination becomes

steeper, the growth in size becomes extremely rapid. As it approaches the base of the hill, the

innocent little snowball has become a fast-moving boulder of snow. Both the little ball and the

boulder have something in common, but a person standing in their respective paths could not

fail to detect a real difference. At what point did the little snowball become a boulder ? At what

point did the New Deal coalitions vanish, to be replaced by new alliances? There is some

ambiguity, but it need not concern us here. Now, at the beginning of the 1980s, the decisive

transformation of the American party coalitions from their New Deal form has surely occurred.

During the New Deal era, each of the two main parties had its reasonably secure bases among

certain social groups. The Republicans were the party of the Northeast, of business, of the

middle classes, and of white Protestants, while the Democrats enjoyed a clear majority among

the working classes, organized labor, Catholics, and the South. And these sources of respective

party strength could be counted upon at all levels of the election process--in voting for president,

Congress, lesser offices, and in underlying party identification. After 1960, however, this

condition of relatively secure party bailiwicks defined by ethnicity, class, and region began

breaking down rapidly. The Democrats emerged almost everywhere outside the presidential

arena as the "everyone" party. The depiction is not intended literally, of course. Rather, it is

meant to describe a novel situation in which one party had more, at least nominal, adherents than

its opposition among virtually all relevant groups. Since 1960 few social collectivities have

given the Republicans regular pluralities either in party identification or in the sweep of

subpresidential voting.

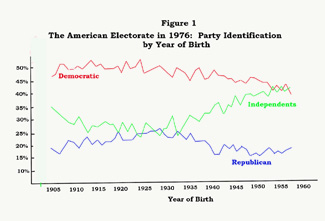

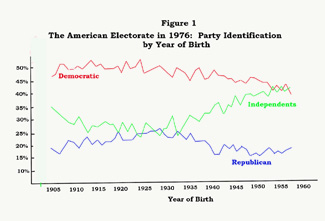

An examination of the party identification of various age strata, social groups, and ideological

clusters in 1976 shows how far the Democratic surge had carried by that date. The Democrats,

for example, were well ahead of the GOP in every age cohort, from the youngest segments of the

electorate to the oldest, and their margin was remarkably uniform. The proportion of

self-described independents did rise steadily, with movement from the oldest to the youngest

voters. The latter had had less time to establish regular preferences. And, of course,

college-trained people, more inclined to see themselves as "independent," were more heavily

represented in the younger cohorts. Still, there was a big and rather even Democratic lead over

the Republicans, one that extended from those people whose earliest political memories go back

to the 1910s and 1920s to those who first saw U.S. politics in the years of Kennedy, Johnson,

and Nixon.

Tables 1 and 2 testify to the breadth of the Democrats' appeal, as compared to that of the

Republicans, by the mid-1970s. Wage workers were less Republican than businessmen and

executives, but a plurality of even the latter identified with the Democrats. Less than one-third of

the business/professional stratum claimed attachment to the GOP. All educational groups

showed a Democratic margin. So did all income cohorts up to the very

prosperous. The

Democrats led the Republicans in every region, among all religious groups,

among virtually all

ethnic groups. People from wealthy family backgrounds preferred the Democrats by

a 2-to-1 margin.

The Democratic lead extended not only to most of the demographic units, but to the principal

ideological groups as well. Survey work by Daniel Yankelovich, for example, showed that the

Democrats far outdistanced Republicans among voters who thought of themselves as liberals

and moderates, and that they even had a comfortable edge among self-described conservatives.

By 1976 there were only a few Republican bailiwicks left.

In defining them, the prominent role of region and ethnicity is striking. White Protestants in the

Northeast remained strongly Republican, continuing a regional/ethnic tradition that reaches far

back into U.S. history. And no group was more decisively Republican than the "Yankees," if the

term is taken to mean white Protestants of British stock residing in the Northeastern states.

Tables 1 and 2 show only party identification. But data on congressional voting reveal the same

pattern. The Democrats had surpassed their GOP opponents across most of the social spectrum.

The middle classes gave higher proportions of their vote to Republican congressional candidates

than did the working classes, but both groups consistently produced large Democratic pluralities.

One reason for the sharp and persisting disparity between the Democrats' uncertain performance

in presidential elections and their domination elsewhere is that voting for the presidency came to

have less and less to do with political party. The parties have been weakened organizationally

since 1960, and the American electorate--better educated, more leisured, with more sources of

political information, and hence more confident of its ability to judge candidates and programs

without reference to their partisan origins--is less strongly attached to the parties and more

inclined to vote in dependently than ever before. The emergence of television as the principal

source of information about candidates, especially at the national level where media resources

are so great, further transformed contests for the presidency (and a few other highly visible

offices in large media-rich states such as New York and California), again reducing the party

role. By contrast, in the less visible, less media-attended offices where candidates are not so well

known, party is much more influential. Since the Democratic party had more adherents and was

more highly regarded than the GOP, the more party emphasis the office received, the better the

Democrats were likely to fare.

But it is the special symbolic importance of the presidency that led it to present particular

difficulties for the Democrats. The intense public visibility of the office almost requires that

various groups and interests attend closely to the style and emphasis of presidential leadership.

Presidential contests thus became the principal arena in which were fought out newly emerging

policy or ideological differences.

The late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States were a period of

extraordinary social change

and turbulence. The liberalism that shaped the New Deal state was incorporated

into a national

consensus, but at the same time a "New Liberalism" emerged--and it was hardly

consensual.

Comprising such positions as support for new standards of personal morality,

cultural values,

and life-styles, a questioning of the merits of economic growth on the grounds

that growth

threatens the "quality of life," and a redefinition of the demands of equality

in the direction of

"equality of result,"; the New Liberalism was fraught with danger for candidates who

espoused, it, simply because a large majority of the population did not share its enthusiasm for

social and cultural change. Dissatisfaction with New Liberalism was especially strong within

the white working class. Wheras policy innovation in the 1930s often involved efforts by the

working class to strengthen its position vis-a-vis business, in the 1960s and 1970s the New

Liberals' projects for social change imposed some significant costs and risks on broad sectors of

the working and lower-middle classes, who did not hesitate to make their unhappiness known.

The New Liberalism was not, however, without its support, especially among more affluent sectors of the society--even though by 1980 it was decisively out of vogue. The upper-middle class, altered by the infusion of a large professional/managerial, public-sector cohort, had been detached from traditional business concerns. Its perspectives seemed to be shaped far more by the universities and the intellectual community, and many of its members had come to share in some of the critical, change--demanding orientations that had long been associated with intellectual life. These upper strata also had a natural concern about life-styles and cultural change--areas in which the higher- status groups have always been more receptive to change than the traditional middle and working classes. And because they were more secure in their position--less threatened by many contemporary efforts at social change, typically residing some distance from the "front lines"the upper strata came easily to a more change-supportive posture in such critical areas as race relations.

The Democrats became the primary party of proponents of both liberalisms. The Democratic

coalition was thus divided, and over the late 1960s and 1970s the tendency to call attention to

this division was far greater at the presidential level than in other contests. The New Liberalism

impacted too strongly on the national stage; it was too divisive for the Democrats to be able to

package, with any degree of regularity, a ticket which left both New Liberals and Old Liberals

comfortably allied. Surely the most dramatic instance of this schism was the 1972 presidential

race, in which George McGovern took up the New Liberal banner and was buried electorally by

a never especially popular Republican. At the congressional level and elsewhere, however, the

party was able to stress the more consensual Old Liberal themes and had little difficulty keeping

its massive, heterogeneous coalition together.

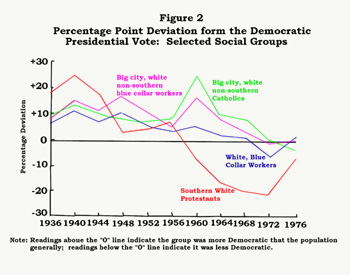

Still, Carter failed to win a majority of the vote among Southern whites. Every "Yankee"

Democratic nominee from Samuel Tilden through Adlai Stevenson won majority backing among

white Southerners--and most did so by overwhelming margins. Southern white Protestants were

a loyal and numerically substantial component of the Roosevelt presidential coalition. They gave

a higher proportion of their ballots to FDR than any other large, politically relevant, social

collectivity. But in 1976 the group was 5 percentage points less Democratic than the national

electorate. [2] On only four occasions from the Civil War to 1976 did a Democratic presidential

nominee lose majority support in the white Protestant South. And these were four presidential

elections between 1960 and 197--all of the elections in this span, that is, except that of 1964.

(Again in 1980, Democrat Carter lost the white South.) In many ways, the 1976 results provided

even more dramatic proof of the scope and permanence of the presidential realignment than did

the McGovern-Nixon contest. If a centrist white Southerner--starting with an extraordinarily

high margin of support in his native Deep South state, contesting against the Republican party

that had been mauled by the most dramatic political scandal in the country's history and

burdened with a poorly performing economy, pitted against a Republican nominee who was the

second choice of his own party in the region and was scarcely the most forceful or charismatic of

contenders--could not win majority backing in the white Protestant South, what Democratic

nominee ever can?

The 1976 vote distribution showed a good bit of similarity to those of other recent presidential

elections. The Democrats in that year did not regain the large margins within the white working

classes which contributed so importantly to their ascendancy in the New Deal era. Urban white

Catholics, and blue-collar workers other than those who are blacks and Hispanics, like Southern

white Protestants, were somewhat more Democratic in 1976 than they had been in the

McGovern-Nixon election, but their electoral standing remained consonant with that of the last

decade and a half. There was no return to the Roosevelt-era high Democratic performance.

So the "old New Deal Democratic coalition" was not "put back together one more time" in 1976.

Jimmy Carter surely received substantial backing from groups that were the building blocks of

the Rooseveltian alignment, and he improved markedly on McGovern's electoral performance,

but the Carter coalition had a quite different base than FDR's. Well before the party's 1980

debacle, the character and makeup of the Democrats' presidential coalition had decisively

changed.

Over the late 1960s and early 1970s, however, a pronounced inversion of the New Deal

class/ideology relationship occurred--with the result that high-status groups in the United States

became more liberal, given the current construction of that category, than the

middle-to-lowerstatus groups across a wide array of issues. This inversion, it must be

emphasized, developed around class and ideology, and it extended to class and party only in

those cases and to the extent that one party was clearly associated with the contemporary

extensions of liberalism. The national Democratic party, far more than its Republican

opposition, became home in the 1960s and 1970s to the New Liberalism, but the extent of the

latter association varied with the individual candidates put forward in each election.

In the presidential elections of 1968 and 1972, the issues of the New Liberalism were unusually

prominent, and the Democrats suffered a marked falling off in their relative standing among

lower-status groups as compared with their support among high- status cohorts. There was

something approaching an actual inversion of the familiar New Deal class/party alignment. In

many instances in 1968 and 1972, groups at the top were more Democratic in their presidential

voting than those at the bottom.

Table 3 reviews the classic pattern of class voting as it persisted throughout the presidential

elections of the New Deal era and into the early 1960s. What had been well established as the

traditional configuration held neatly for the several sets of groups represented in this table, and

indeed, for all the various socioeconomic groupings which can be located with survey data.

Thus, only 30 percent of all white Americans of high socioeconomic status voted for Democratic

nominee Harry Truman in 1948, compared with 43 percent for Truman among middle-status

whites and 57 percent among low-status white voters. In the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon election the

same relationship can be seen, with Kennedy backed by just 38 percent of the high-status group,

by 53 percent of the middle-status, and by 61 percent of those of low socioeconomic standing.

By 1968, however, the relationship had changed markedly. Humphrey was supported that year

by 50 percent of high status whites under thirty years of age, but by only 39 percent of their

middle-status age mates and by just 32 percent of young, low-status electors. The newly

emergent conformation was even clearer in 1972, when the somewhat distorting factor of the

Wallace candidacy was removed. Among whites--for blacks constitute a deviating case of voters

who are disproportionately in the lower socioeconomic strata but overwhelmingly

Democratic--those with college training were more Democratic than those who had not attended

college; persons in the professional and managerial stratum were more Democratic than the

semi-skilled and unskilled work force; and so on. McGovern was backed by 45 percent of the

college-educated young, but by only 30 percent of their age mates who had not entered the

groves of academe. Comparing 1948 and 1972, we see a reversal of quite extraordinary

proportions.

We may conclude, without need of extensive elaboration, that the McGovern candidacy of 1972

distinguished itself far more than the 1976 Carter candidacy by a commitment to the style,

programs, and constituencies of the New Liberalism. The tendencies to an electoral inversion

paralleling those of class and ideology, then, should have been more pronounced in 1972 than in

1976. And so they were. But the elements of an electoral inversion so clearly seen in 1968 and

1972 were not wiped away in the Carter-Ford contest. There was a fairly steady increase in the

Ford proportion with movement up the socioeconomic ladder, however socioeconomic status is

measured. But there was no return to the class voting of the New Deal years. Louis Harris

found that grade school- educated whites were about 14 percentage points more Democratic in

1976 than were their college-trained counterparts.

Whites from families earning less than $5,000 a year were approximately 16 points more for

Carter than were whites with annual family incomes of $15,000 and higher. Data made

available from the Election Day "exit" polls of the New York Times, CBS News, and NBC

News show similar distributions. In the 1930s and 1940s, by way of contrast, high-status and

low-status whites were separated by between 30 and 40 percentage points in presidential

preference.

Lower-status cohorts were relatively more Democratic, compared with their upper-status

counterparts, in the contest between Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter than in either of the two

preceding elections. But the Democratic contender in 1976 did not regain the big relative margin

among lower-class voters enjoyed by his Democratic counterparts in the New Deal years, nor

that which Kennedy achieved as late as 1960. Carter ran a campaign which minimized rather

than heightened the "social issue" concerns of lower-status whites. And it should be noted that

actual social conditions in 1976 made it far easier for a Democratic nominee to accomplish this

than it had been in 1968 and 1972. Still, the altered meaning of liberalism--and hence of the

national Democrats as the liberal party--together with the changed social position of the white

working classes and the professional/managerial groups, had precluded a return to the class

voting patterns of the New Deal epoch.

College-trained professional and managerial people, especially the younger age groups, remain

consistently more liberal than the noncollege blue-collar groups on a wide range of social and

cultural issues. On matters of economic policy, however, they are often more conservative,

although much less decidedly so than during the New Deal. The Democratic party came, in the

1960s and 1970s, to be associated with both the new social liberalism and the old economic

liberalism, and as a consequence it evoked contradictory responses within both the upper and the

lower socioeconomic categories. The decline in class distinctiveness in voting, and the

tendencies toward inversion, came as a result--among white Americans. Black Americans must

be treated separately, because their electoral choices have not been accounted for by the

class/ideology dynamics we have been describing [3]

That this argument has centered on whether a new realignment burst upon the U.S. political

scene in 1980 seems to me most unfortunate because it is so untheoretical. As noted, new

alignments have been emerging in response to broad social changes ever since the New Deal,

and especially since 1960. The 1980 balloting signalled the continuation and the elaboration

ofthese changes, not some sudden new departure. And it has been evident over the 1970s that the

primary direction of these shifts is toward dealignment, not realignment.

A realignment encompasses the movement of large numbers of voters across party lines,

establishing a stable new majority coalition. In a dealignment, by way of contrast, old coalitional

ties are disrupted, but this happens without some stable new configuration taking shape. Voters

move away from parties altogether; loyalties to the parties--and to their candidates and

programs--weaken, and more and more of the electorate "comes up for grabs" each election.

Over the 1970s an impressive body of theory and data developed which supports the argument

that the present era in American electoral politics is one of dealignment and party decay, which

specifies the sources of this development, and which identifies its implications for American

political life. The progress of dealignment has been giving recent electioneering its distinctive

cast.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s one began noting, with increasing frequency, signs of a

vast transformation of the political parties and of the nature of voters' attachments to them. For

one thing, the national party organizations, never notably robust, experienced a major decline

and loss of functions. Within the Congress and in the conduct of presidential nominations,

political individualism triumphed over institutional and collective requirements. I have

described these developments in some detail elsewhere (Ladd 1979, 1981c).

A weakening in public attachment to the parties has contributed to their institutional decline as

much as it has resulted from that decline. Increasing numbers of voters think of themselves as

independents, and regularly cross party lines with abandon in election contests (Ladd 1978, pp.

320 - 33). The proportion of the public lacking confidence in both of the major parties has

grown substantially (Ladd 1981a, pp. 3 - 7). The electorate is less shaped and located by stable

partisan loyalties now than at any time in the last century.

An electorate thus "cut loose" is potentially much more volatile than one held in place by the

anchors of party. This potential for volatility that party dealignment creates was amply realized

over the 1980 presidential campaign, but it had been apparent for at least the preceding decade

(see Ladd 1 1981a 0 1 1981b ).

The changes occurring in the parties and in the public's loyalties to them over the 1960s and 1970s thus were not building to a "critical realignment" of the sort that took place in the late 1920s and 1930s. The changes were momentous enough, and they brought about the dissolution of the New Deal party system, but they were not yielding a coherent new majority. Old attachments were being disrupted without, for the most part, new ones being built in their place. The full impact of electoral dealignment was to be felt in the volatile, party-free voting of 1980.