UNREGULATED GROUPS WIELD MILLIONS TO

SWAY VOTERS

Special Interests, Millionaires Skirt Campaign Limits.

By Stephanie Simon

Times Staff Writer

October 30, 2006

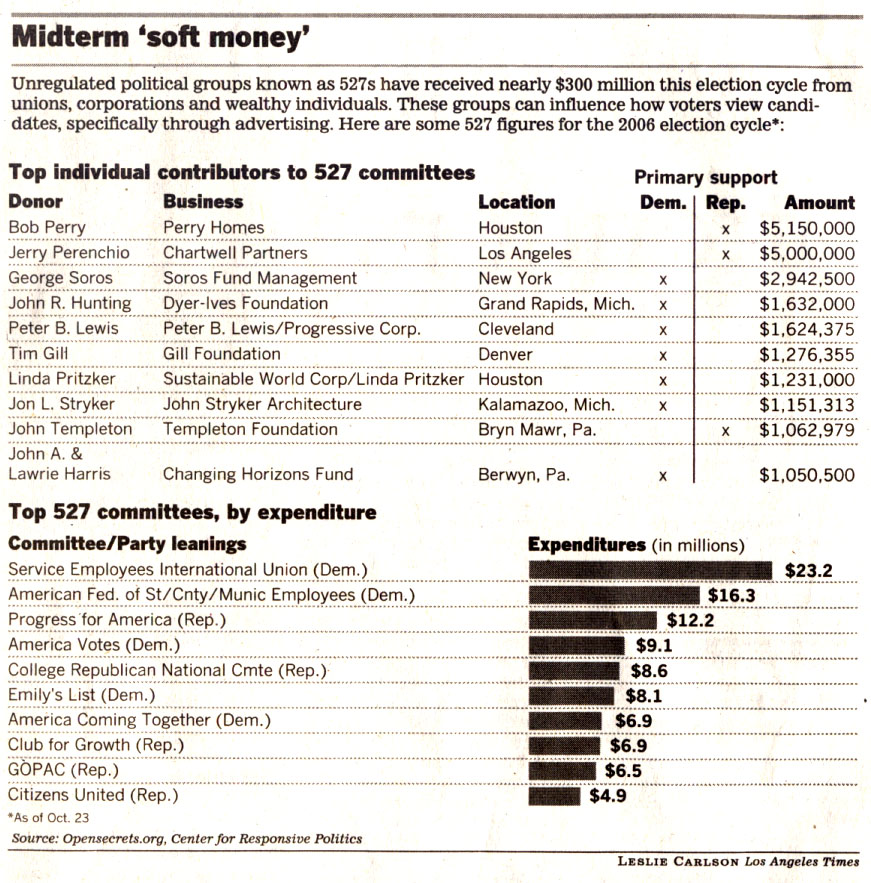

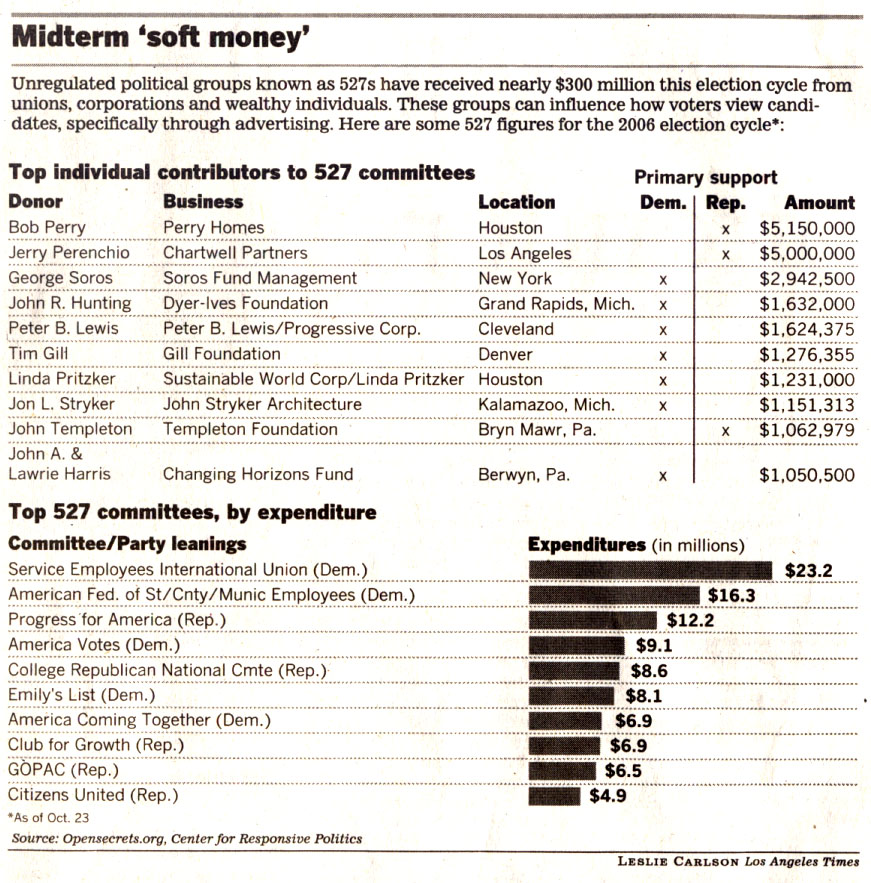

Sterling, Colo. — Unions,

corporations and wealthy individuals have pumped nearly $300 million

this

year into unregulated political groups, funding dozens of aggressive

and sometimes shadowy

campaigns independent of party machines.

The groups, both liberal and conservative, air TV and radio spots,

conduct polls, run phone banks,

canvass door-to-door and stage get-out-the-vote rallies, with no

oversight by the Federal Election

Commission. Set up as tax-exempt "issue advocacy" committees, they

cannot explicitly endorse

candidates. But they can do everything short of telling voters how to

mark their ballots.

Because they can accept unlimited donations from any source, the

committees — known as 527s —

have emerged as the favored vehicle for millionaires and interest

groups seeking to set the political

agenda.

"It's become the new way to do business in politics," said Pete

Maysmith, a national director of Common

Cause, a nonprofit that lobbies for more transparency in campaign

finance.

Named for a section of the IRS code, 527s have been around for years

but became a political force in

2004 after the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 — also known as

the McCain--Feingold Bill —

limited donations to political parties. Groups such as Swift Boat

Veterans for Truth on the right and

America Coming Together on the left contributed $600 million that year,

with a heavy focus on the

presidential race.

The cash flow is lower this year because it's a midterm campaign,

but 527s and a related type of

organization known as 501(c)s have expanded their reach. With the Nov.7

election days away, the

groups are flooding the airwaves in state and local races as well as

congressional contests.

By far the largest chunk of unregulated money — nearly $60 million —

comes straight out of union

treasuries and is used mostly to benefit Democratic candidates and

causes. Conservatives are fighting

back with multimillion-dollar donations from a California TV executive

and the Texas developer who

financed the Swift Boat ads.

In California, unregulated funds — mostly donated by New York

developer Howard S. Rich — are

bankrolling the campaign for Proposition 90, which would limit the

government's ability to seize private

property. In Missouri, such money paid for a celebrity-studded TV ad

opposing a ballot initiative on

stem-cell research.

In Ohio, a 527 has run some of the most provocative radio spots of

the campaign season, with an

African American announcer accusing Democrats of "decimating our

people" by promoting abortions of

"black babies." Another group funded by black Republicans has bought

airtime on radio stations in

Maryland and Florida to assert that Democrats "have bamboozled blacks"

and want to keep them in

poverty.

'Yeah, right'

Here in eastern Colorado, a 527 called Coloradans for Life has

raised more than $1 million to oppose

Republican Rep. Marilyn N. Musgrave — spending nearly as much on the

race as the Democratic

candidate. A radio ad championing "the unborn" gave many voters the

impression the group was an

anti-abortion organization attacking Musgrave from the right. In fact,

it's funded by three millionaire

liberals.

At a recent reception for rural Republicans, chiropractor Philip

Pollock rushed up to Musgrave to

complain about what he called the "underhanded, back-door" tactic.

"I just heard those ads. Coloradans for Life — totally ridiculous,"

he said. "What happened to …

campaign finance reform?"

"You mean getting the big money out of politics?" Musgrave asked.

Pollock shook his head in disgust. "Yeah, right."

The campaign finance reforms that took effect for 2004 limit

individuals to about $100,000 in total

contributions to all candidates, parties and political action

committees per election cycle. Parties and

PACs remain extremely influential. PACs, for instance, are expected to

funnel more than $1 billion to

candidates this year by bundling contributions from trial lawyers, beer

wholesalers, pharmaceutical

makers and other groups.

But more than 70 individuals have maxed out their PAC and party

contributions; if they want to pump

more cash into the election, they must donate to 527s and 501(c)s. Many

prefer that approach because

they can control how the money is used.

The 501(c) groups do not have to disclose donors or itemize

spending. The 527s must report donors

and expenses, but the groups are often ephemeral, forming under a

generic name for a few months and

then dissolving. That makes it all but impossible to sort through IRS

filings and pick out which

organizations will get involved in which races. By law, these groups

cannot coordinate their activity with

candidates.

"The first warning you have is often when you see their ad on TV,"

said Robert Duffy, a political scientist

at Colorado State University who tracks the groups. "These 527s throw a

whole lot of unpredictability

into campaigns."

In 2004, Democrats dominated 527 fundraising, led by financier

George Soros and insurance magnate

Peter B. Lewis, who each contributed more than $23 million. This year,

Soros and others are focused

instead on long-term party-building efforts, such as strengthening

liberal think tanks and building a

national voter database.

Two Republicans now top the donors' list compiled by the Center for

Responsive Politics, a nonprofit

research firm based in Washington.

Homebuilder Bob Perry, who financed the Swift Boat ads, has pumped

$5 million into TV ads attacking

Democratic congressional incumbents in Georgia, Iowa and Oregon as

tax-and-spend liberals. GOP

backer A. Jerrold Perenchio, who owns the Spanish-language television

network Univision, has spent $5

million on ads in Missouri and Ohio featuring images of terrorism and

warnings about those who would

"cut and run" in Iraq.

Here in Colorado, the 527 targeting Musgrave is funded by siblings

Patricia Stryker and Jon L. Stryker,

billionaire heirs to a medical-supply fortune, and by Tim Gill, a

software developer.

They bankrolled a similar effort in 2004, with TV ads that portrayed

Musgrave picking soldiers' pockets

as an announcer accused her of voting to cut veterans' benefits.

Their TV campaign this year has been far less dramatic but still

controversial, accusing Musgrave of

cutting a program that protects clean drinking water. In fact, Musgrave

did not vote on that issue, though

she has cast other votes that environmentalists say would weaken water

protection.

Thanks, but no thanks

Musgrave's Democratic challenger, Angie Paccione, watched the water

ad with a sinking heart. Like

many candidates, she regards 527s as a mixed blessing. The independent

group has undoubtedly given

her campaign a boost; when the national Democratic Party canceled

$630,000 worth of TV ads in the

district, Patricia Stryker wrote a check for $720,000 to keep

anti-Musgrave spots on the air.

But Paccione has no control over the message. Attacks such as the

pickpocket dramatization could

alienate voters. She considers ads like the one on water a waste of

money.

"Clean drinking water?" Paccione said. "Holy smokes! There's a

litany of things you could do against

Marilyn Musgrave. Clean drinking water is not one of them."

Paccione's own ads portray Musgrave as a conservative ideologue.

A lawsuit pending in federal court aims to rein in 527 activity. But

political analysts say they don't expect

much to change, even if the case succeeds.

"Political money is like water. It will find an outlet," said

Jeffrey M. Berry, a political science professor at

Tufts University. "If 527s are banned, will another vehicle pop up?

Absolutely."

*

stephanie.simon@latimes.com